|

In 1900, photographer

Edward Curtis traveled to Montana to witness a Piegan Sun Dance. As the Indians made offerings to the sun against

a stark prairie landscape, Curtis was intensely moved. In 1900, photographer

Edward Curtis traveled to Montana to witness a Piegan Sun Dance. As the Indians made offerings to the sun against

a stark prairie landscape, Curtis was intensely moved.

He thought it might be the last of its kind. The ceremony had already been outlawed in the United States, and the

federal government was taking steps to assimilate Native Americans.

After two more visits to tribal ceremonies in Arizona that same year, Curtis conceived his life work. He would

make a photographic record of Indian tribes before their traditions were lost.

"The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites

possessed by no other," he wrote, "consequently the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit

of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once

or the opportunity will be lost for all time."

The project garnered the support of President Theodore Roosevelt and financier J. P. Morgan. The first volume of

The North American Indian appeared in 1907. The New York Herald hailed it as the most ambitious enterprise in publishing

since the production of the King James Bible.

By the time the twentieth and final volume was published in 1930, Curtis was professionally and personally ruined.

Interest in Native American subjects dwindled as the country suffered through the Great Depression. Years in the

field had taken their toll on Curtis's health and led to the end of his marriage. Curtis died in 1952, his work

on American Indians nearly forgotten.

The story of Curtis's work and its impact on contemporary understandings of Native American culture is told in

Coming to Light: Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indians, a documentary by Anne Makepeace. It will be scheduled

for broadcast as part of the PBS series American Masters.

"I knew I had great material, but how to shape it was very, very challenging," says Makepeace,

who wrote, produced, and directed the film, which had originally been conceived as a biographical drama. "If

it works, it looks like it was easy. But it wasn't." "I knew I had great material, but how to shape it was very, very challenging," says Makepeace,

who wrote, produced, and directed the film, which had originally been conceived as a biographical drama. "If

it works, it looks like it was easy. But it wasn't."

Makepeace says she was drawn to Curtis because of his classically American life story of self-made success and

tragic failure.

Curtis was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin, in 1868. While still a boy, he built his own camera using a lens his

father had brought home from the Civil War. With only a sixth-grade education, Curtis taught himself photography

and, in 1891, went into business in Seattle with a fellow photographer. Curtis started his own commercial studio

in 1897.

As he built the business, Curtis looked for other sources of inspiration. He began taking pictures of Northwest

Coast Indians, and in 1898 he joined the Harriman Expedition as its official photographer. On that scientific trip

to Alaska, Curtis worked with naturalist George Bird Grinnel, who would later invite him to the Sun Dance in Montana.

Earnest in his desire to learn about all aspects of Indian religious life, Curtis practiced persistence. It took

him six years to convince Sikyaletstewa, the Hopi Snake Chief, to allow him to participate in a ceremonial snake

hunt.

"Once the confidence of the Indians gained, the way led gradually through the difficulties," Curtis wrote

in his general introduction, "but long and serious study was necessary before knowledge of the esoteric rites

and ceremonies could be gleaned."

Even then, his subjects did not always cooperate. In 1904, he paid three Navajos to help him capture a Yei be Chei

healing dance on film. But, as shown in Makepeace's film, the hired dancers performed the ceremony backwards and

did not reveal its most sacred parts.

Coming to Light originally centered on Curtis's work with the Hopi. A script was developed with support from the

NEH and state humanities councils in Arizona and California. Warned that older Hopis disapproved of women exposing

their legs, Makepeace wore long skirts while tracking down interview subjects in northern Arizona.

While interviewing the Hopis, she became increasingly interested in the lives of the Indians pictured by Curtis.

Eventually, she reconceived her film as a documentary in which she could compare Curtis's images with images of

contemporary Native American life.

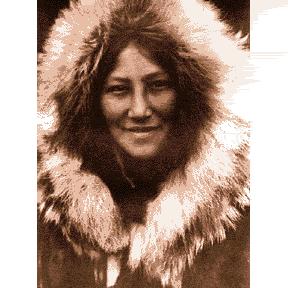

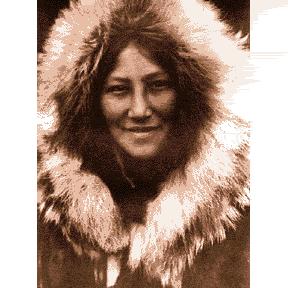

By the summer and fall of 1998, Makepeace and a small crew were tracking down descendants of Curtis's

original subjects on Crow, Hopi, Navajo, and other Indian reservations throughout the western United States. She

also retraced the photographer's voyage to Nunivak Island off the southwestern coast of Alaska. By the summer and fall of 1998, Makepeace and a small crew were tracking down descendants of Curtis's

original subjects on Crow, Hopi, Navajo, and other Indian reservations throughout the western United States. She

also retraced the photographer's voyage to Nunivak Island off the southwestern coast of Alaska.

In making decisions about what to include in the documentary, Makepeace faced some of the same resistance that

Curtis did.

"You're putting all the pictures into today's world which is not right," an Indian man tells Makepeace

at a Blackfoot powwow. "Our relatives are supposed to be let down. It's supposed to be over. We're not here

to bring it up from what's in the past."

Makepeace comments that such antagonistic encounters were rare. "I actually wanted to raise more controversy

than I actually did," she says.

She also faced dilemmas in the editing room. One involved footage of a Hopi Snake Dance shot by Thomas Edison.

The Hopis had never meant for this ceremony to be recorded. Makepeace compromised by including a long shot of the

dancers from Edison's film, then cutting to a shot of the crowd that had gathered to watch. She also included a

Snake Dance shot by Curtis in 1900.

"I had to walk a fine line and I hope that the line that I walked was respectful enough," she says. Walking

that line meant not only gaining the trust of Indians, but of Curtis's surviving family. Jim Graybill, the photographer's

only surviving grandchild, initially declined to help Makepeace. He was worried about past criticism of Curtis,

which found his images to be romantic and not reflective of Native American life at the time.

After seeing an excerpt of filmed interviews that Makepeace put together as part of a 1998 symposium,

Graybill changed his mind and provided her with previously unpublished pictures and other materials. "It took

eight years to win his trust," recalls Makepeace. After seeing an excerpt of filmed interviews that Makepeace put together as part of a 1998 symposium,

Graybill changed his mind and provided her with previously unpublished pictures and other materials. "It took

eight years to win his trust," recalls Makepeace.

Opinions about Curtis's work have varied over the years.

In his foreword to the first volume of The North American Indian, President Theodore Roosevelt wrote, "In

Mr. Curtis we have both an artist and a trained observer, whose pictures are pictures, not merely photographs;

whose work has far more than mere accuracy, because it is truthful."

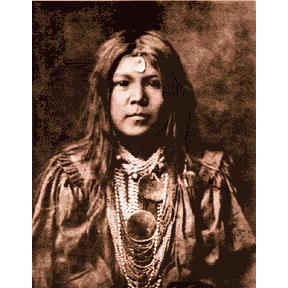

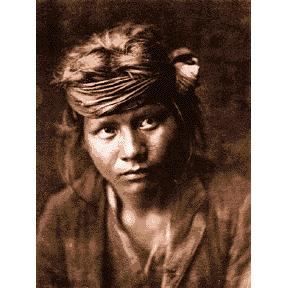

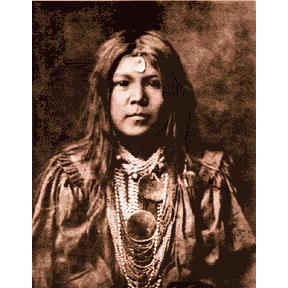

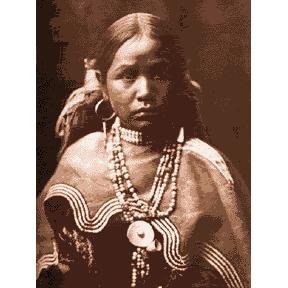

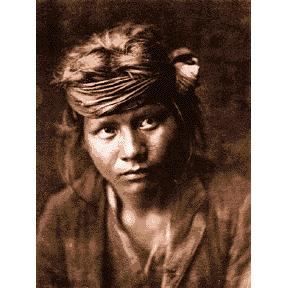

But the photographs do not always tell the whole story. In order to portray traditional customs and dress, Curtis--using

techniques accepted by many anthropologists of his day--removed modern clothes and other signs of contemporary

life from his pictures. A portrait of a Piegan lodge, for example, originally showed an alarm clock between two

seated men. Curtis cut the clock out of the negative and included the retouched image in The North American Indian.

Curtis also depicted a Crow war party on horses, even though there had been no Crow war parties for years. He often

romanticized the images by using soft focus and idealized settings.

"They certainly have contributed to a popular image of noble demise," says Curtis Hinsley, Regents Professor

of Arts and Sciences at Northern Arizona University and a consultant on Coming to Light.

By putting Curtis's writings and photographs and interviews with Indians living today, says Makepeace, "I

could show how contemporary Native Americans feel about the pictures."

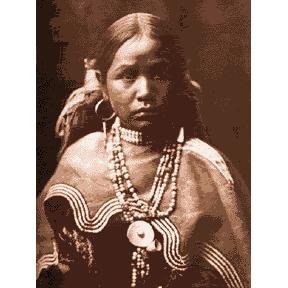

The film highlights the contrast between popular imagination and everyday reality. Jerry Potts, a descendant of

a famous Blackfoot guide, speaks about the photograph of an elaborately dressed Indian boy.

"A lot of the photographs show the traditional people in their traditional garb," Potts says. "They're

depicting a side of us that goes back thousands of years, but they weren't showing what Indian agents and governments

and everybody else were doing to our people at the same time. The state that Indian communities were in was really

terrible."

Curtis began his photographic project during the height of U.S. government efforts to assimilate the

Indian population. Most Indians were restricted to reservations and made dependent on government agents for food,

clothing, and other essentials. Tribal governments and native languages were suppressed and religious ceremonies

were banned. Indian children were taken away to boarding schools, taught English, and trained to fit into white

mainstream society. Curtis began his photographic project during the height of U.S. government efforts to assimilate the

Indian population. Most Indians were restricted to reservations and made dependent on government agents for food,

clothing, and other essentials. Tribal governments and native languages were suppressed and religious ceremonies

were banned. Indian children were taken away to boarding schools, taught English, and trained to fit into white

mainstream society.

Hinsley says that projects like The North American Indian were informed by the assumption that Indian culture was

doomed and that nothing could be done about it. "Our goal therefore is to record what went before us and show

respect to it," he explains.

"There is no question that there's a lot of falsifying going on," Hinsley acknowledges. But he cautions

that the photographs must be viewed in the cultural context in which they were produced. And despite his controversial

techniques, Curtis still produced informative work, depicting the lives of women, children, and people at work

alongside more dramatic portraits of Indian warriors.

Paula Richardson Fleming, who is a photo archivist with the National Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian

Institution, agrees that the photographs are a valid resource for studying Native American culture.

"Both Curtis and the Indians that he worked with were very interested in reporting and documenting an earlier

time," Fleming says, noting that "the people who would have known what costumes looked like or had costumes

themselves or proper clothing would have been in a position to help him."

Most of the Indians whom Makepeace interviewed were intrigued by the representations made by Curtis's

camera. Some surprised her with their fond reactions. In the film, Edward B. Harvey, a Navajo, looks at a picture

of sand paintings showing Navajo myths. A translator conveys Harvey's reaction: "He said that he's very happy

to see these photos. It brings back memories of his dad, you know. I guess his dad used to do all kinds of ceremonies." Most of the Indians whom Makepeace interviewed were intrigued by the representations made by Curtis's

camera. Some surprised her with their fond reactions. In the film, Edward B. Harvey, a Navajo, looks at a picture

of sand paintings showing Navajo myths. A translator conveys Harvey's reaction: "He said that he's very happy

to see these photos. It brings back memories of his dad, you know. I guess his dad used to do all kinds of ceremonies."

Theoria Howatu, a Hopi, is also shown discussing her grandmother's experiences posing with other Hopi girls in

fancy costumes, grinding meal.

"I think they normally wore cotton dresses," Howatu says in the documentary. "They rarely wore this

outfit unless there was a special occasion."

Her grandmother, she recalls, laughed at having to simultaneously work while looking into the camera.

Since its debut at the Sundance Film Festival in January, "the response has been really terrific," says

Makepeace. Many in the audience at Sundance were Native Americans who had grown up looking at Curtis photographs.

Currently, Makepeace is negotiating for the film's theatrical release. A website is being planned that will show

footage not included in the finished film.

Although Curtis died in obscurity, his photographs have never been entirely out of circulation. His haunting portraits

of Indians in ceremonial costumes and against dramatic natural backgrounds became more than a record of the Native

American past. They helped shape contemporary perceptions of Indian culture. Whatever flaws Curtis's photos contain,

Makepeace considers them "a hugely important record."

Pedro Ponce is a writer in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

NEH provided $222,121 in funding for "Coming To Light: Edward S. Curtis

and the North American Indians," which airs on PBS American Masters next winter. http://www.neh.gov/publications/humanities/2000-05/curtis.html

Edward Curtis Biography

http://www.curtis-collection.com/curtis.html

|

In 1900, photographer

Edward Curtis traveled to Montana to witness a Piegan Sun Dance. As the Indians made offerings to the sun against

a stark prairie landscape, Curtis was intensely moved.

In 1900, photographer

Edward Curtis traveled to Montana to witness a Piegan Sun Dance. As the Indians made offerings to the sun against

a stark prairie landscape, Curtis was intensely moved. "I knew I had great material, but how to shape it was very, very challenging," says Makepeace,

who wrote, produced, and directed the film, which had originally been conceived as a biographical drama. "If

it works, it looks like it was easy. But it wasn't."

"I knew I had great material, but how to shape it was very, very challenging," says Makepeace,

who wrote, produced, and directed the film, which had originally been conceived as a biographical drama. "If

it works, it looks like it was easy. But it wasn't." By the summer and fall of 1998, Makepeace and a small crew were tracking down descendants of Curtis's

original subjects on Crow, Hopi, Navajo, and other Indian reservations throughout the western United States. She

also retraced the photographer's voyage to Nunivak Island off the southwestern coast of Alaska.

By the summer and fall of 1998, Makepeace and a small crew were tracking down descendants of Curtis's

original subjects on Crow, Hopi, Navajo, and other Indian reservations throughout the western United States. She

also retraced the photographer's voyage to Nunivak Island off the southwestern coast of Alaska. After seeing an excerpt of filmed interviews that Makepeace put together as part of a 1998 symposium,

Graybill changed his mind and provided her with previously unpublished pictures and other materials. "It took

eight years to win his trust," recalls Makepeace.

After seeing an excerpt of filmed interviews that Makepeace put together as part of a 1998 symposium,

Graybill changed his mind and provided her with previously unpublished pictures and other materials. "It took

eight years to win his trust," recalls Makepeace. Curtis began his photographic project during the height of U.S. government efforts to assimilate the

Indian population. Most Indians were restricted to reservations and made dependent on government agents for food,

clothing, and other essentials. Tribal governments and native languages were suppressed and religious ceremonies

were banned. Indian children were taken away to boarding schools, taught English, and trained to fit into white

mainstream society.

Curtis began his photographic project during the height of U.S. government efforts to assimilate the

Indian population. Most Indians were restricted to reservations and made dependent on government agents for food,

clothing, and other essentials. Tribal governments and native languages were suppressed and religious ceremonies

were banned. Indian children were taken away to boarding schools, taught English, and trained to fit into white

mainstream society. Most of the Indians whom Makepeace interviewed were intrigued by the representations made by Curtis's

camera. Some surprised her with their fond reactions. In the film, Edward B. Harvey, a Navajo, looks at a picture

of sand paintings showing Navajo myths. A translator conveys Harvey's reaction: "He said that he's very happy

to see these photos. It brings back memories of his dad, you know. I guess his dad used to do all kinds of ceremonies."

Most of the Indians whom Makepeace interviewed were intrigued by the representations made by Curtis's

camera. Some surprised her with their fond reactions. In the film, Edward B. Harvey, a Navajo, looks at a picture

of sand paintings showing Navajo myths. A translator conveys Harvey's reaction: "He said that he's very happy

to see these photos. It brings back memories of his dad, you know. I guess his dad used to do all kinds of ceremonies."