|

|

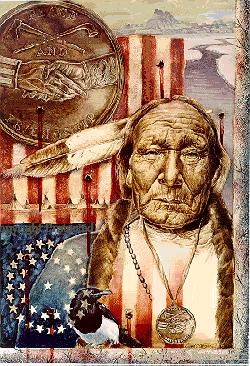

Chief's Battle to Reclaim Past Continues

by Ron Jackson Staff Reporter The Oklahoman

|

Skulls, once decapitated by frontier soldiers, stared back. "That was a difficult moment for all of us," recalled Hart, his voice strained by the vision in his mind. "You could see the bullet holes in some of the skulls." Hearts beat hard and tears flowed. And with the swiftness of a prairie fire, Hart's life was forever altered. So went the summer of 1993 when Hart and other Cheyenne people reclaimed the skulls of 18 Cheyenne ancestors. Five of the skulls -- once shipped for observation to the old Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C. -- belonged to victims of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. One skull represented a girl between the ages of 10 and 12. She too had obviously been shot in the head. For Hart and his dedicated colleagues, it was a healing moment -- a victorious moment -- when the wrongs of the past were made less painful with the prospects of a proper burial. Each skull received a ceremonial burial in handcrafted cedar boxes July 10, 1993, at a packed cemetery in Concho, the headquarters for the Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribe. Hart proudly remembered the historic occasion as the first time the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 had been tried and proven by a tribal nation. The act allows Indian people to reclaim ancestral remains, as well as any ceremonial objects, from any museum that has received federal funds. Today, Hart serves on the seven-member National Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Review Committee. He was appointed to the post in 1993 by Interior Secretary Bruce Babbit. On Thursday and Friday, Hart's work will again take center stage with 14 other panelists at the Native American Repatriation Summit in Oklahoma City. Some 550 tribal leaders across the United States have been invited to the two-day summit, co-hosted by the Chickasaw and Choctaw nations. Arizona State University law professor Rebecca Tsosie, conflict resolution expert Diane LeResche and Bureau of Indian Affairs archaeologist Joe Watkins are scheduled to be among the featured panelists. Hart said most tribes are getting up to speed on the graves protection and repatriation act. "The main problem we have now is that there is a backlog of work," he said. An estimated 200,000 remains are yet to be reclaimed. Another pressing issue that challenges Hart and other repatriation leaders is the topic of "culturally unidentifiable Native American remains." Hart thinks the answer rests in regionalization, and his fellow committee members have agreed. The weight of such responsibility would fall to regional alliances of Indian nations to determine how and where such remains will be interred. "Indian tribes and nations must build coalitions to successfully conduct repatriation of culturally unidentifiable Native American human remains," Hart said. "This summit will be a good place to begin or strengthen those coalitions." Leading on such issues has seemingly become Hart's destiny. Born Feb. 24, 1933, on the federally allotted land of his grandfather, John Peak Heart, Lawrence Hart spent the first 51/2 years of his life in the presence of traditional family elders. He was raised initially by his grandparents, who primarily spoke Cheyenne. Heart, a Cheyenne peace chief who spelled his last name differently, was a respected Native American Church missionary, renowned as a dynamic orator. He was also known as a progressive leader who favored education. Heart died in 1958, but not before requesting of fellow chieftains that his grandson take his place at the council fires. The chiefs agreed, and in a tepee lodge later that year, Hart -- a former Marine fighter pilot -- was ordained a Cheyenne peace chief. "I had to get out of the military," Hart quipped. "You can't be both a fighter pilot and peace chief at the same time." At the ceremony, a respected Cheyenne peace chief named Crooked Nose approached Hart with advice. "He told me, 'You'll have to live a good, moral life,'" Hart recalled. "He said, 'You have to especially look out for children and elders and live life as a peacemaker. ... Not to engage in quarrels, and that it would be a hard life.' "I consider myself fortunate to have been raised by my grandfather. In retrospect, I think my grandfather was grooming me to take his place."

Gordon L. Yellowman, Sr., Cheyenne NAGPRA Representative, and

Robert W. Fri, Director, NMNH, The

Original Peacemakers |

|

|

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. section 107. |

|

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry. |

|

CLINTON,

OK -- Cheyenne Peace Chief Lawrence Hart and friends stared at the long row of tables in a silent room at the Smithsonian

Institution's National Museum of Natural History.

CLINTON,

OK -- Cheyenne Peace Chief Lawrence Hart and friends stared at the long row of tables in a silent room at the Smithsonian

Institution's National Museum of Natural History.