|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

June 2021 - Volume 19

Number 6

|

||

|

|

||

|

Coast Salish people

persevered in the Puget Sound region despite settlers who took their

land and forced them into unfair treaties

|

||

|

by David B. Williams

- Special to The Seattle Times

|

||

Editor’s note: This is an edited excerpt from David B. Williams’ new book, “Homewaters: A Human and Natural History of Puget Sound,” published by University of Washington Press. About the Book THE BACKSTORY Learning and appreciating the history of Puget Sound’s Indigenous people is the key to creating a positive future

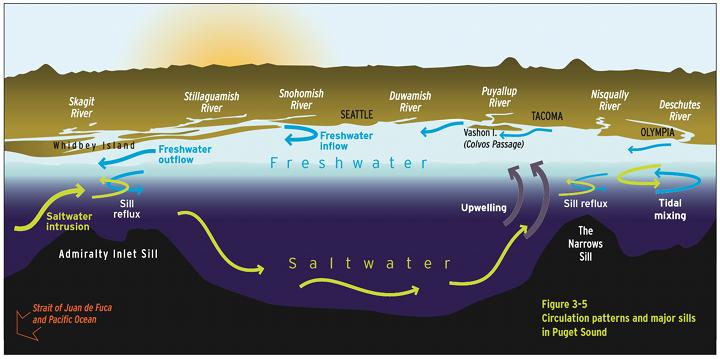

DURING A ROUTINE archaeological survey in 2009 for a project to restore salmon habitat in Bear Creek, in Redmond, Bob Kopperl and other archaeologists uncovered several artifacts. Digging deeper, they excavated a foot-thick mat of reddish-brown peat. Tests showed that the peat might be as much as 10,000 years old. Bob and his team eventually unearthed several thousand artifacts at the Bear Creek site, which he describes as the oldest evidence of human existence in Puget Sound so far. The archaeologists concluded that the area’s first human residents arrived at least 12,500 years ago, making Puget Sound one of the longest continuously inhabited landscapes in the Lower 48 states. Pollen studies show that Puget Sound’s first human inhabitants would have found an open habitat of bogs, wetlands and ponds interspersed with pine and minimal amounts of spruce, Douglas fir and true fir. The Savannah-like habitat was ideal territory for hunting the great beasts that had moved into the postglacial landscape, including mastodon, giant sloth, bison and short-faced bear.

Unfortunately for archaeologists, the Redmond site does not include any mammal bones. It does offer rich evidence of stone tools, such as projectile points, knives, scrapers and hammerstones, made primarily from local rock. The diversity of artifacts at the site implies a deep connection between the people who made the tools and the landscape they inhabited, Kopperl says. They knew where to find the raw materials they needed, and most likely they traveled to gather them. They knew how to make use of different rock types to manufacture tools for specific purposes. “These were people who had an intimate knowledge of subsistence across several habitats. They knew where to stop, find good stone, and make a living,” he says. I cannot leave Puget Sound’s first people without considering one of the smallest and rarest artifacts discovered in the Bear Creek dig: a salmon bone, the only bone found at the Redmond site. It is brownish-gray from heating, cracked in half, and smaller than a raisin. Because the bone was burned, no DNA remains by which to identify the species it came from, though sockeye, which makes use of lakes, seems the most likely. The bone and the salmon protein residue found on the Bear Creek tool might be the earliest evidence for people eating salmon in Puget Sound. No sooner had our species arrived here than we discovered what is arguably the most defining and sustaining food of the region.

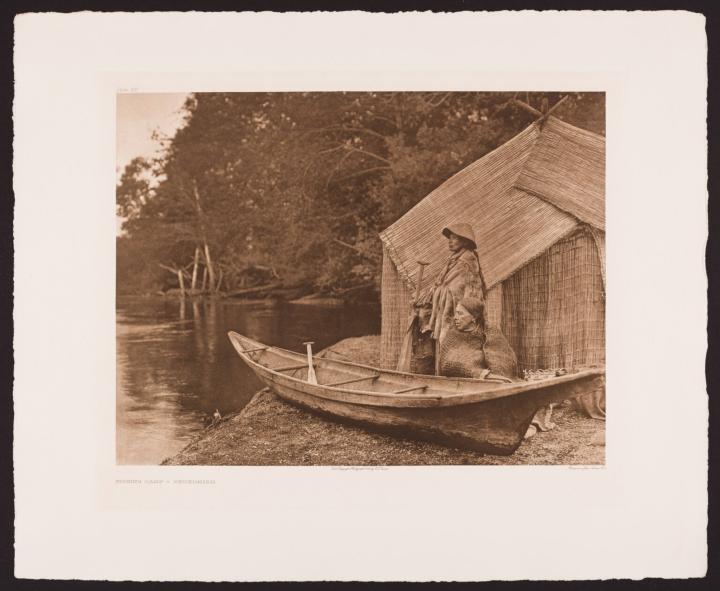

Although evidence for land use at Redmond ends around 10,000 years ago, other local sites show that the sheltered body of water continued to attract people. Until around 7,000 years ago, there were still small, highly mobile groups of hunters and gatherers living in an environment far different from what we know at present. The climate was hotter and drier; the ecosystem was Savannah-like with vast open spaces and big vistas, amply populated with oaks. Great herds of deer and elk would have roamed the lands and fed on nutritious acorns. Beginning around 7,000 years ago, though, the Puget Sound climate gradually grew cooler and moister, becoming comparable to the area’s current climate by about 5,000 years ago. The new conditions led to the development of closed-canopy forest of the kind familiar to present-day residents of Puget Sound, with conifers towering over a nearly impenetrable understory. OVER TIME, THE people of Puget Sound developed a culture based on coexistence with the region’s abundant natural resources. Extended family groups established winter villages, which were the home base and heart of social and ceremonial life. At other times of year, they moved to seasonal camps to acquire useful plants and animals. They continuously modified their technologies and strategies to increase their food harvests. In doing so, they created a sustainable and resilient lifestyle based on reciprocity between bands of people inhabiting different watersheds, which persisted up to the time of contact with Europeans.

Despite numerous attempts to eliminate the Native people of Puget Sound, they survived, and continue to maintain their long-term traditions and connections. In essence, the treaties created two distinct ways of relating to the land in the Puget Sound region. Gone was the stewardship of the past 12,500 years. Plants and animals were now products to be acquired, processed and sold. In the view of the waves of newcomers, the land was there to be owned and used, water a dumping ground. At the same time, the treaties codified Native people’s rights to hunting, fishing and gathering, which preserved, albeit on the margins, a traditional way of life. The paradigm established by the treaties is still shaping the relationship to place of the residents of Puget Sound.

David B. Williams is an author, naturalist, educator and an archaeology curatorial associate at the Burke Museum. His newest book is "Homewaters: A Human and Natural History of Puget Sound." His many books include the award-winning "Too High and Too Steep: Reshaping Seattle’s Topography." Find him on Twitter at @geologywriter.

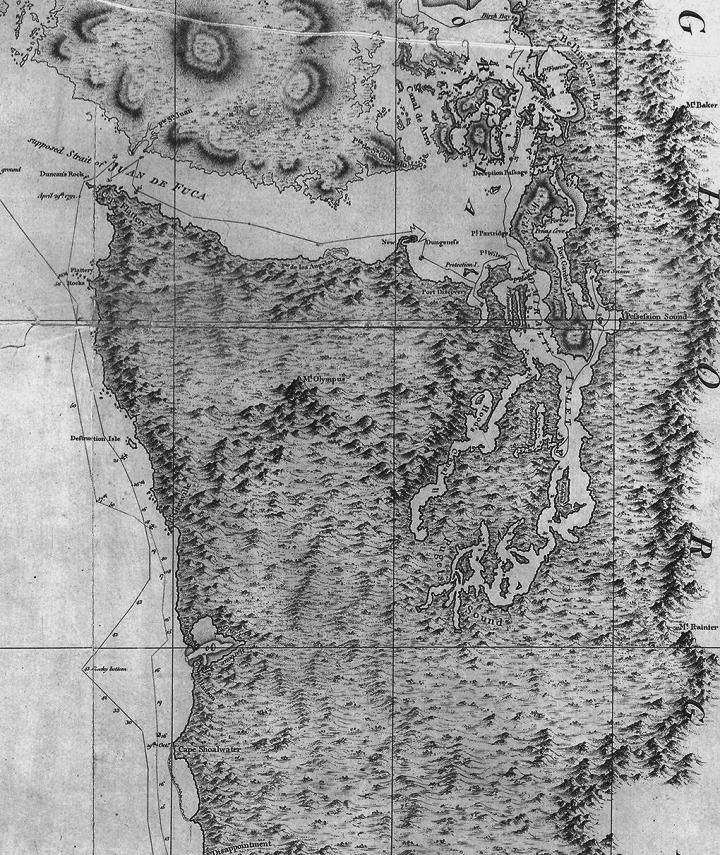

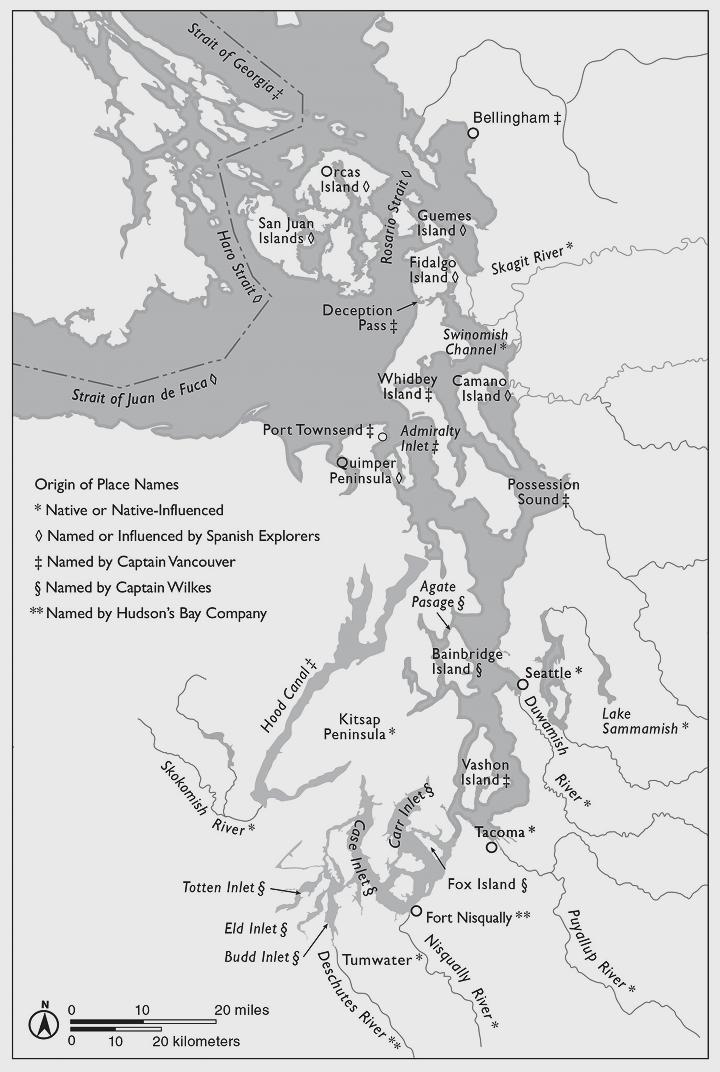

Two events in the last quarter of the 18th century forever changed the lives and culture of Puget Sound’s Indigenous residents. The first was the arrival of smallpox around 1781-82, which led to the deaths of a catastrophically high number of Coast Salish people. The second was the arrival of Europeans, the first of whom sailed into the Strait of Juan de Fuca in 1788. That “discovery” of the Strait ultimately led to George Vancouver’s sailing into x???lc (the Lushootseed name for Puget Sound) four years later. How did smallpox reach the Sound before Europeans did? Historian Robert Boyd believes it was introduced via a shipwreck on the Oregon coast. A second theory holds that Spanish explorers could have brought the disease during their journeys to Nootka Sound on the west side of Vancouver Island in the late 1770s. Cole Harris, a retired University of British Columbia geographer, believes that Native people carried the smallpox virus from the Great Plains to the Columbia River and finally north into Puget Sound via trade networks. After initial contact, the disease spread through Coast Salish populations. Although we might never know exactly how smallpox reached Puget Sound, we understand how it enabled postcontact settlers to wrest control of the land. “The eventual result, everywhere,” wrote Harris, “was severe depopulation at precisely the time that changing technologies of transportation and communication brought more and more of the resources of the northwestern corner of North America within reach of the capitalist world economy. Here was an empty land, so it seemed, for the taking, and the means of developing and transporting many of its resources.”

Although the Spanish had been the first Europeans to arrive in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, it was George Vancouver’s expedition that explored the inlet to the south. During their month of exploration in the waterway (in May 1792), the British came away with two distinct impressions. Their disparaging descriptions of Indigenous people were typical of European explorers of the time. One village was the “most lowly and meanest of its kind” and the people “ill made” and of “pilfering dispositions.” And yet the explorers observed that the Native residents had abundant and varied food, including salmon, deer, clams and “a small well tasted wild onion.” They were also willing to share their knowledge of the geography and to help free a British boat stuck in the mud. Vancouver further wrote of “several tribes of Indians, whose behavior had been uniformly civil, courteous, and friendly.” The British were much more complimentary about the landscape. (Archibald) Menzies wrote of towering ferns, bountiful oysters, thick forests and “salubrious & vivifying air.” (Peter) Puget added that the flowers were “by no Means unpleasant to the Eye.” Vancouver summed up their thoughts. “To describe the beauties of this region, will, on some future occasion, be a very grateful task to the pen of a skilful panegyrist,” he wrote. The British reaction to the people and landscape of Puget Sound at the time of first contact makes sense in context. It was an encounter of groups with two completely different worldviews. In a land of abundance, the Coast Salish people had thrived for thousands of years with relatively little negative impact on the area’s natural resources; they hunted, fished, gathered, traded and traveled according to the seasons. Their major worries had been warfare and raids from other Salish Sea inhabitants. Just as they probably found it hard to grasp the motives and culture of the British explorers, the explorers struggled to understand a culture without any form of industry they recognized. Britain at this time was in the midst of the Industrial Revolution; progress and success were signaled by steam, brick and metal, not hook and line or bow and arrow. There was virtually no chance that men who represented this new world of industrialization could have responded positively to the peoples and cultures they encountered in Puget Sound. And, clearly they made little effort to learn from, understand, or respect the people they met. The next Britons to reach Puget Sound had a different mindset. Instead of pursuing imperial expansion, they came in search of trade. They also came by a much different route, traveling overland from the south. The first to do so, 40 or so men on an exploratory trip for the Hudson’s Bay Company, reached present-day Eld Inlet, at the southernmost end of Puget Sound, on Dec. 5, 1824. Although the HBC men found the route favorable, the land bountiful, and the Coast Salish people friendly, nine more years passed before the HBC arrived to stay. In the spring of 1833, the company started erecting Fort Nisqually in an open space about 12 miles east of modern-day Olympia. By October, houses, a store with space for trading, and sheds had been built. THE ESTABLISHMENT OF Fort Nisqually marked a new era in Puget Sound. For the first time, Coast Salish people and “King George men,” as the locals called the British arrivals, had a chance to live and work together. Whether they were involved in trade, religion, medicine, or conflict, both sides “developed ways of dealing with each other that usually worked to all parties’ perceived advantage,” according to the historian Alexandra Harmon. The British harbored negative stereotypes, attempted to proselytize, and exploited Native resources, but they also learned to respect the trading and hunting skills of the people who visited the forts, recognizing that their own survival depended on good relations with the Indigenous people. In Harmon’s view, the Native residents might have seen the new arrivals as unclean, bad-mannered, and ignorant of basic survival skills, but interaction with the King George men could increase prestige and lead to better relations with other Coast Salish people long considered to be enemies. Unfortunately, the mostly positive initial relations between newcomers and longtime residents did not last. Whereas the British had built their relationship on “lucrative trade and coexistence,” wrote Harmon, the “United States was a nation that had limited citizenship to ‘whites’ and defined itself largely in opposition to ‘Indians.’ ” The first town to be named was New Market, at the falls on the Deschutes River, where it enters Budd Inlet. Among its first settlers were the families of Michael Simmons and George Washington Bush, who had traveled together from Missouri. Of longer-lasting importance than the new town name, which survived only a few years before being changed to Tumwater — the Chinook jargon place name — Bush, Simmons and the other settlers built a gristmill and sawmill, the first on Puget Sound. On Oct. 27, 1848, the Puget Sound Milling Company delivered 12,993 board feet of lumber to the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Nisqually. By 1853, as the logging industry thrived, the population of Bostons (the Native term for settlers from the United States) in the counties bordering Puget Sound had increased to 2,058. In contrast, the number of Indigenous people had plummeted because of the introduction of smallpox, measles, influenza and syphilis. Cole Harris and Robert Boyd estimate that in the 100 years after Europeans arrived, diseases led to a population decline that exceeded 30 percent and might have been as high as 80 to 90 percent. The new arrivals brought with them a fundamentally different attitude than had prevailed for thousands of years in the Puget Sound area. An individual Coast Salish family might retain the right, or privilege, to fish or harvest shellfish from a particular location, but that spot was not owned by the family in the sense that settlers understood ownership, whereby one could claim exclusive use of it and transfer that right to other people. Indigenous people’s relationship to land and natural resources focused (and still focuses) more on maintaining the productivity of living resources and the relationships between those who controlled access to these resources and those allowed to use them. This control equated to wealth and the ability to give away goods. These relationships centered on sharing access and building connections and reciprocity: they involved stewardship rather than outright ownership.

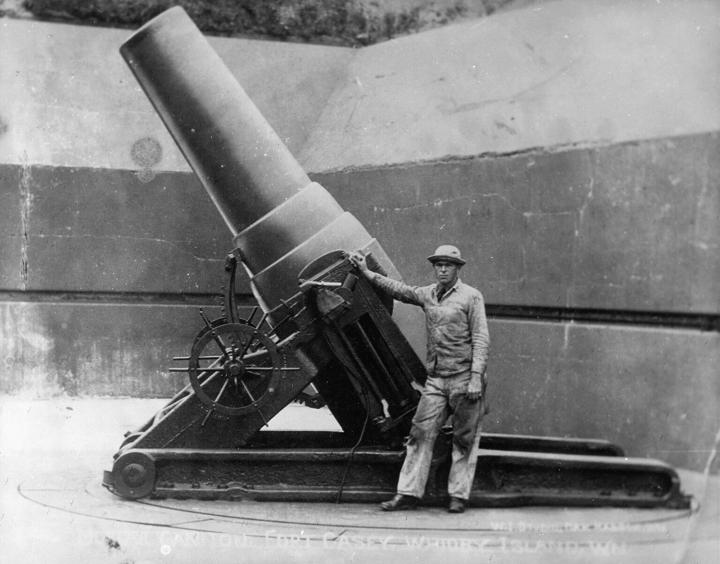

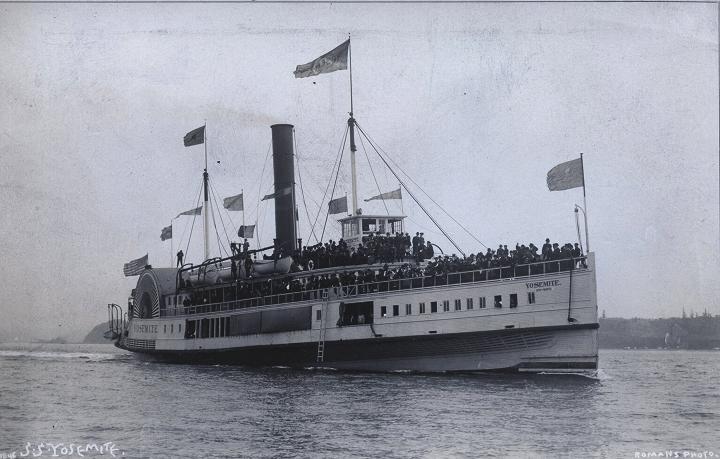

In contrast, to the newcomers, private land ownership in the American sense was a source of status and power. The Bostons believed that ownership was their natural right and their destiny; they were supposed to own the land from sea to shining sea. They did not see Indigenous people as rightful or legitimate owners of the land. BY THE SUMMER of 1854, Washington Territory Gov. Isaac I. Stevens had begun to consider how to address the struggles between settlers and residents. Stevens held his first treaty signing at Medicine Creek, where it empties into Puget Sound near the Nisqually River. “Negotiation” is often the word associated with a treaty, but, as J. Ross Browne wrote in an 1858 report, “none of the so-called treaties with the Indians are anything more than forced agreements, which the stronger power can violate or reject at pleasure.” Two more treaties quickly followed. The treaty signings were the most significant steps in a process that had begun with George Vancouver and his men. When the British first arrived, they had “claimed” the land around Puget Sound for King George III. These gestures had little practical meaning, as they consisted primarily of naming features on the landscape after themselves and discharging the royal salute. Nor had settler actions during the years 1792-1853 had much official or permanent effect, except for the horrible spread of disease. Though HBC employees had moved into the area, their claims to the land were only slightly less tenuous than Vancouver’s, and only the King George men inhabited the HBC land in 1846, when Britain ceded its claims to the United States. Few believed that this new American claim meant much, either. On Nov. 4, 1846, the chief factors of HBC at Fort Vancouver, James Douglas and Peter Skene Ogden, wrote to William Tolmie at Fort Nisqually, “Business will of course go on as usual, as the treaty will not take effect on us for many years to come.” By 1853, though, the Americans had begun to establish a new reality in Puget Sound. With the signing of the treaties, the Bostons, or at least the federal government, now owned nearly all the land around Puget Sound. The new arrivals had begun to develop towns and to extract natural resources, often at rates that far exceeded the environment’s capacity to replenish them. Their population grew from 4,928 in 1860 to 180,812 in 1890. The Coast Salish people certainly were not gone. Many of them had been shunted to reservations with drastically reduced access to the lands that had sustained them, but they still retained and practiced many of their cultural traditions. They maintained complex kinship relations over long distances. They fished, collected shellfish, harvested roots and berries, and hunted marine mammals at the “usual and accustomed places” guaranteed by the treaties. They also found employment in Puget Sound’s nascent towns, providing key labor in many logging communities.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||