|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

April 2021 - Volume

19 Number 4

|

||

|

|

||

|

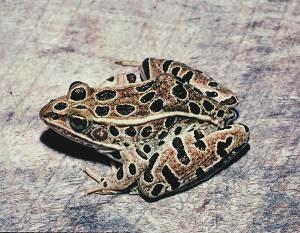

TOAD AND FROG FACTS

|

||

|

by Missouri Department

of Conservation Staff

|

||

|

View toads and frogs in the field guide.

COLORFUL, HARMLESS, VOCAL AND VALUABLE GOOD INDICATORS OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH LIFE HISTORY From tadpole to adult DEFENSES Toads cannot jump as fast as frogs. To escape a predator, toads defend themselves by producing toxic or unpleasant-tasting skin secretions that are released when the animal is seized. Due to their toxic skin, toads are not a popular food among most predators. Even their eggs and tadpoles are said to be toxic. Frogs also have skin glands which cause them to have a bad taste. But the secretions are not generally as strong as those of toads, so frogs are eaten by a much wider variety of predators. People normally are not affected by the skin secretions of toads and frogs, though human eyes are sensitive to these substances. The pain and burning that result when even a slight amount of skin secretion gets in one of your eyes is something you will never forget. It is important to wash your hands after handling a toad or frog. The age-old myth that toads can cause warts on people is false. FACTS Missouri has 26 species and subspecies (or geographic races) of toads and frogs. Toads and frogs differ from salamanders by having relatively short bodies and lacking tails at adulthood. Being an amphibian means that they live two lives: an aquatic larval or tadpole stage and a semi-aquatic or terrestrial adult stage. Of the 6,145 species of amphibians currently recognized in the world, there are approximately 4,145 species of toads and frogs. The largest species is the goliath frog, Conraua goliath, of the west coast of Africa, which may have a head-body length of nearly 14 inches and may weigh as much as 7 pounds. One of the world’s smallest frogs is Eleutherodactylus iberia, which has no common name and lives in the tropical forests of Cuba. It is less than a half-inch long as an adult. This frog is so tiny that females of the species are able to produce only one egg during the breeding season. DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TOADS AND FROGS Toads

Frogs

TOAD AND FROG CALLS FILE ATTACHMENTS |

||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

.jpg)