|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

March 2021 - Volume

19 Number 3

|

||

|

|

||

|

There Are Many Versions

Of The Tlingit 'Raven' Story, But Its Truth And Hopeful Message

Are Universal

|

||

|

by Miranda Belarde-Lewis

- Special to The Seattle Times

|

||

Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from "Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight" by Miranda Shkík Belarde-Lewis and John Drury (University of Washington Press, $50 hardcover, 144 pages, 115 color illustrations). The book has been available at Tacoma's Museum of Glass during an exhibition of the same name that runs through Sept. 2, featuring Singletary's glass art. The book is now available more widely. All glass art is by Singletary, an American Tlingit, with photos by Russell Johnson. In this essay, Belarde-Lewis examines the multiple versions of the "Raven and the Box of Daylight" stories, and explains how she and Singletary curated the exhibition.

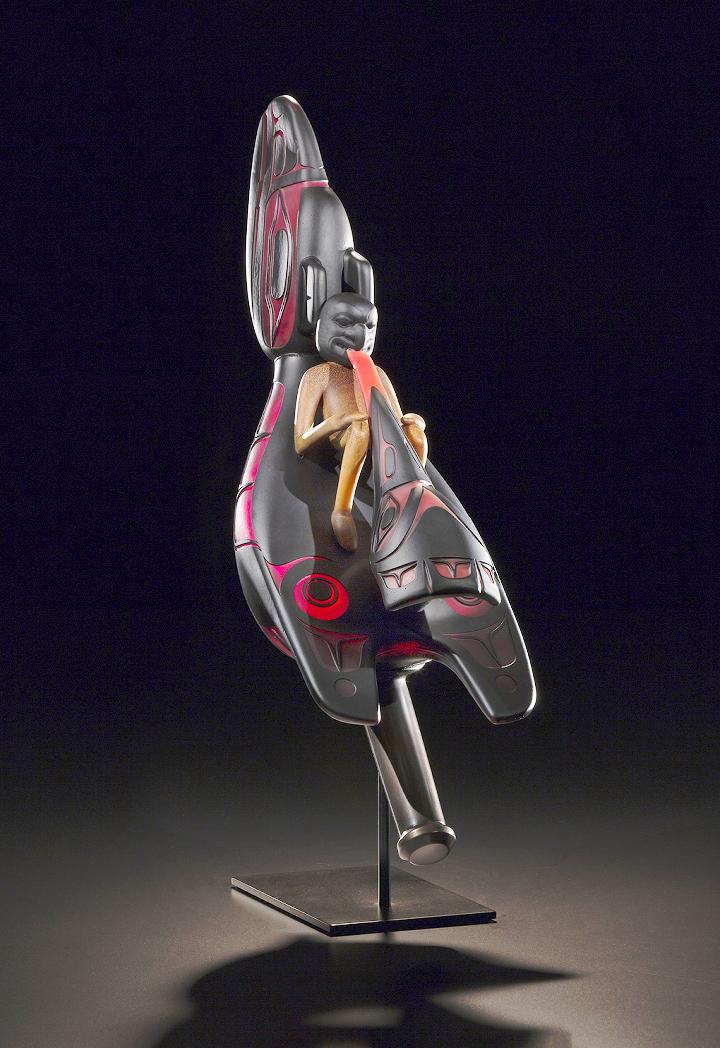

ONE DAY, MY SON asked me, "How do we know if history is true?" He was 9 years old at the time, and his question shocked me. I explained to him that there are those who remember what happened, there is the evidence of what happened, and there are those who write it down. I told him that if enough of the stories match, then we all agree — that is what happened. I reminded him that this is how it "easily" works when the written word is the documentation for history, and that when it comes to Native history, we have to get the story right every time we tell it. High-level discussion with a 9-year-old. But his question has immediate relevance to this exhibition. There are countless Raven stories in the Tlingit community, and there are many versions of how Raven came to bring the light to the world. The stories are not necessarily contradictory, but they do emphasize different points and have different details, depending on whom the caretaker of that story was and how he or she was taught to tell the story. During the four years that glass artist Preston Singletary and I have been working on an exhibition with Tacoma's Museum of Glass, he and I have continuously wrestled with questions at the intersection of oral history, the defining nature of art and the universal elements contained within this particular Raven story. THE BACKSTORY: Illuminating the treasured story of Raven, and its shared values THE EXHIBIT: The Museum of Glass exhibition, 'Preston Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight,' explores a Tlingit story Some of the questions raised: How can this exhibition showcase the universal aspects of the "Raven and the Box of Daylight" story? What is the best way to explore Tlingit oratory through glass? Who has the authority to tell the stories? How do we as curators and institutions encourage and support artists who are affirming tribal truths and history through their art? When there are several versions of the same tribal story, is it possible to craft one exhibition narrative that honors multiple tellings of the story?

When Singletary and the Museum of Glass asked me to curate this exhibition in late 2014, the planning of an exhibition based on the iconic Tlingit story of "Raven and the Box of Daylight" was well underway. This story describes the time when the world was in darkness: "Nass Shaak Aankáawu (Nobleman at the Head of the Nass River) was hoarding many treasures, including the light. When Yéil (Raven) learned that the man had a daughter who drank from a stream every morning, Yéil turned himself into a hemlock or spruce needle and floated into her cup. She drank him; became pregnant; and Yéil, born in human form, became the love of their lives. Nass Shaak Aankáawu provided every luxury and toy to his precocious grandson. When the child cried for the boxes that held the stars, the moon and the sun, his grandfather could not refuse him. One by one, Yéil T'ukanéiyi (Raven Baby) incessantly cried for and released the stars, the moon and the daylight, much to the dismay of Nass Shaak Aankáawu but much to the benefit of the people and animals of the world. Realizing he was the victim of extreme deceit, Nass Shaak Aankáawu forever marked Yéil by holding him in the smoke of the fireplace, altering his color, turning him from the white spiritual being into the black color he is today."

THE STORY OF "Raven and the Box of Daylight" has captivated the imagination of Tlingit peoples for thousands of years, just as it has captured the imagination of non-Tlingit anthropologists since the late 1700s. Its appeal is multifaceted: It has drama, it helps explain the world, and it has many similarities to other iconic stories from other cultures and religions that are easily compared. Its symbolism and the way elements of it resemble other stories around the world have helped it to be regurgitated ad nauseam by academics. Many a non-Native children's book author has appropriated the story. The late linguist, poet and author Xwaayeená Richard Dauenhauer called the story "one of the most hackneyed" of Tlingit stories. Although the story has been appropriated many times over, it has resonance within the Tlingit community. It's still our story. Shdal'éiw Walter C. Porter, a beloved and now-deceased elder from the Tlingit village of Yakutat, Alaska, spent more than 20 years examining the story and its differences, depending on whom was telling it. He dissected its symbolism, analyzed its messages and compared it to stories from around the world. After meeting in 2004, Singletary and Porter began a dialogue based on the storytelling power and potential of Singletary's glass art. Porter studied the symbolism and messages contained within Tlingit stories and compared them with the symbolism and messages of stories in the Bible; with the teachings of Buddha; with ancient European traditions; and with our indigenous relatives in Oceania, Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand). It was Porter's encouragement and his focus on the universal traits of the "Raven and the Box of Daylight" story that inspired Singletary to pursue this exhibition, a resolve that was strengthened with urgency after Porter's passing in 2013.

There are dozens of Raven stories. Raven is a trickster, and regularly finds himself in trouble, or finds that the shortcuts used to benefit him almost always backfire. Many times, the consequences of his actions have influenced the world as we now know it. There are quite a few "Raven and the Box of Daylight" stories; for this exhibition, we examined five of them. Two of the tellings came from Porter, from Yakutat, Alaska. The other tellings came from Daanawáakh Austin Hammond, from Haines, Alaska; Lugóon Sophie Smarch, from Whitehorse, Yukon Territory; and Kaasgéiy Susie James, from Sitka, Alaska. As I crafted the exhibition narrative, Singletary and I learned from and were influenced by the various stories and tried to take into account the different details that Singletary wanted to emphasize. Our primary goal is to honor the essence of the story without veering too far off into one version of it. We have made it a priority to acknowledge the people and the details they know to be true. We have an obligation to them, to recognize and honor how they understand their own history as it is embodied in this particular Raven story. Here is a deeper look at four different elements of the exhibition and, within each, the variances between the stories, Porter's analysis of the portion of the story and the pieces Singletary created.

RAVEN IN THE WATER In all the stories, Raven transforms into some sort of plant and drops himself into the daughter's drinking water; however, the details of his trials to be ingested by her vary. In Porter's tellings, the daughter does not realize her water contained Raven, and she drank him without incident. In his many presentations on the "Raven and the Box of Daylight" story, Porter routinely drew attention to the use of pure, blessed and holy water in many of our world's religious and cultural practices. In James' telling, the daughter complains and does not want to drink from the bentwood box cup; the servants cannot keep the water free from the spruce needles that keep finding their way into her cup. After repeated attempts to clean the water, her mother tells her to drink it anyway. Ironically, her mother tells her that the spruce needle is not going to harm her. Smarch told that Raven kept appearing in the water, and the girl and her mother kept throwing the dirty water out but eventually had to drink it. In all of the versions of the story, Raven persisted and prevailed in his plan to sneak into the daughter's water and be ingested by her. In the Hammond version, a hole is dug near the river to help distill it. The water is retrieved from the hole, and a feather is pulled through the water to test its purity. Raven disguised himself as a hemlock needle and fooled the feather so he would not be detected as the feather was pulled through the water. Hammond reminds the listener that during this point of existence, Raven is what people of European descent call a spirit, that he was a supernatural being, and he was able to trick the feather into pulling through and not catching him in the water. The fact that the daughter choked on a hemlock needle was not without notice by the Nobleman. The man asked, "Why didn't the feather tell us?"

IMMACULATE CONCEPTION In their tellings, both Porter and Hammond made direct references to the similarities in the "Raven and the Box of Daylight" story and the Immaculate Conception detailed in the Bible, the event that led to the birth of Jesus Christ. Hammond's version explicitly ties together the similarity to the biblical story, stating, " … yes, the story of the Lord Above. Look at that, my friends. The story of how the Lord Above was born." In one of Porter's tellings, he asked the audience: If the daughter became pregnant and was not yet married, she became pregnant as what? As a virgin. He then asks, "Where else have we heard this story before … ?" Hammond and Porter recognized the similarities of the Immaculate Conception in the stories. Hammond's version makes the point that the stories are similar, while Porter's telling views them as universal traits found in stories around the world. Singletary often recalls how engaging Porter's tellings were of this aspect of the story. He would interact with the audiences, employing strategies like a pastor, calling for and getting a response from the whole room: "And who here has heard a story like that before? Who else was born to a virgin mother?" He would always solicit a response.

HUMBLE BIRTH In several versions of the "Raven and the Box of Daylight" story, a pit is dug in the ground and lined with luxurious furs and skins in preparation for the daughter to give birth; however, she had a difficult and prolonged delivery. James told that Raven is the one who did not want to be born on martin skins and thus into luxury. In her version, it was baby Raven who wanted a humble birth because what he was doing was for the "poor people" without light. Hammond told of an Elder, sometimes referred to as "the woman who is curious," who insisted baby Raven needed a humbler area to be born on. In both James' and Hammond's tellings, the fine furs and skins were replaced with moss. Hammond compared the Nobleman's desire to have his grandchild born into luxury with the first attempt of Mary and Joseph to rent a room at an inn. Singletary has long been struck by this strong point of similarity between the "Raven and the Box of Daylight" stories and the Bible, as well as its strength as an incredibly poignant visual.

WHITE/BLACK RAVEN In many versions of "Raven and the Box of Daylight" — including both ethnographic accounts and popular English versions of the story — at the beginning of his journey, Raven is white, one marker of his supernatural status. Tlingit scholar and professor Maria Williams wrote in her children's book "How Raven Stole the Sun (Tales of the People)" that Raven was "pure white from the tips of his claws to the ends of his wings." Hammond described Raven as a white or translucent being early on in his telling of the story. Depending on whom is telling the story, the details of how Raven became black differ, but the results are always the same. Smarch described how angry Raven's grandfather was when Raven released all of his treasures into the sky. In her telling, he gathered the pitch from all around the house, placed it into a bentwood box and threw it in the fire. Raven could not find the smoke hole and flew around in the black smoke, becoming the black bird we know today. Raven sacrificed his supernatural state of being in order to bring light to the world. The final room of the exhibition reveals a world drenched in light and the realms that were created when the beings were exposed to full daylight. The beings that jumped into the sky with fright became the sky beings. The beings that ran for cover in the woods became part of the forest realm. Those that dived into the water became water creatures. Those who stood tall and brave (or foolishly did not run for any cover) remained as the human Tlingit people.

MY SON ASKED me how we know whether history is true. Native peoples and indigenous communities have witnessed the banishment of our histories into the realm of myths and legends, in no way regarded as legitimate "history." Despite the negative and harmful treatment of our spirituality, our cultural practices and our stories, we have lived through this before with many of our stories intact. Native artists have the unique ability to make our truths tangible and accessible to a wide variety of viewers. Art helps us recognize each other's humanity, a vital act if we wish to move beyond this contentious moment in time. The story of "Raven and the Box of Daylight" contains messages and symbolism of hope, forgiveness, tolerance, love and sacrifice — messages and symbolism that encourage humans to be kinder toward each other. Earlier, I asked how we would proceed with an exhibition narrative when there are several versions of the same tribal story. The way that Singletary and I have reconciled the multiple tellings is to acknowledge the different versions, both in the flow of the exhibition and explicitly in this essay. By going back to the essence and the messages of our stories, we are being reminded that our history carries the strength and wisdom of our ancestors. For those of us blessed to be from communities that still have these stories, and our own interpretations of what these stories mean to us, we are now in the unique position to bring that history fully into the present to share with the world. May all of our stories help guide us into our collective future.

Miranda Shkík Belarde-Lewis (Ph.D.), curator of 'Preston

Singletary: Raven and the Box of Daylight,' is an independent curator

in the Seattle area and an assistant professor at the University

of Washington's Information School. She works to highlight and celebrate

Native artists, their processes and the exquisite pieces they create.

She is enrolled at Zuni Pueblo and is a member of the Takdeintáan

Clan of the Tlingit Nation. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||