|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

January 2021 - Volume

19 Number 1

|

||

|

|

||

|

Archaeologists Identify

Famed Fort Where Indigenous Tlingits Fought Russian Forces

|

||

|

by Megan Gannon - SMITHSONIANMAG.COM

|

||

|

The new discovery

builds upon the knowledge passed down by generations of Indigenous

communities about the clash from two centuries ago

For thousands of years, the Tlingit people made their home in the islands of Southeast Alaska among other indigenous peoples, including the Haida, but at the turn of the 19th century, they came into contact with a group that would threaten their relationship with the land: Russian traders seeking to establish a footprint on the North American continent. The colonists had been expanding into Alaska for decades, first exploiting Aleut peoples as they chased access to sea otters and fur seals that would turn profits in the lucrative fur trade. The Russian American Company, a trading monopoly granted a charter by Russian tsar Paul I just as British monarchs had done on the continent's east coast in the 17th century, arrived in Tlingit territory around Sitka in 1799. On the eastern edge of the Bay of Alaska, the settlement was at an ideal location for the company to advance its interests into the continent. Stopping them, however, was resistance from a Tlingit community uninterested in becoming colonial subjects. In an attempt to oust the colonizers, the Kiks.ádi clan launched an attack on a Russian outpost near Sitka called Redoubt Saint Michael in 1802, killing nearly all of the Russians and Aleuts there. The Kiks.ádi clan members were prepared for retaliation after a tribal shaman predicted the Russians, led by Alexander Baranov, would return. The Tlingits built a wooden fort to stave off the foretold attack, which would come in the fall of 1804 when Baranov returned with his forces to demand that they surrender their land. The Kiks.ádi instead prepared for battle. They successfully defended the initial assault from the Russians and Aleuts, but after six days, with supplies dwindling, the clan's elders decided to withdraw and embark on a survival march north. The Russians quickly established a fortified presence in Sitka, and with that new foothold, they would claim the entirety of Alaska as a colony, which they would later sell to the United States in 1867 for $7 million. Today, Sitka National Historical Park commemorates the site of a battle that changed the course of Alaska's history, but the precise location of the Tlingit fort has remained unknown until now. More than two centuries later, archaeologists have finally pinpointed the stronghold where native Alaskans resisted colonization through the use of ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetic instruments.

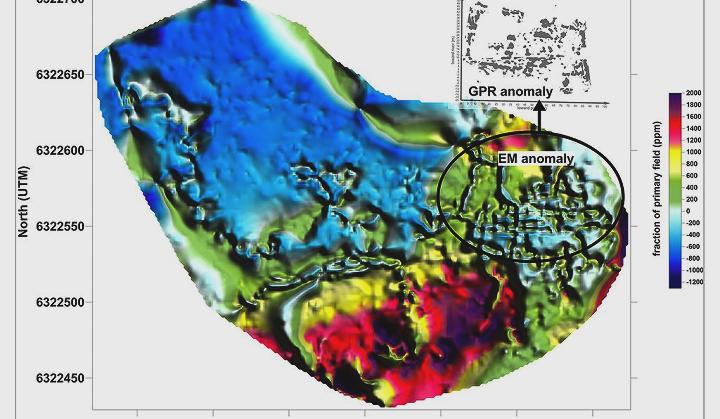

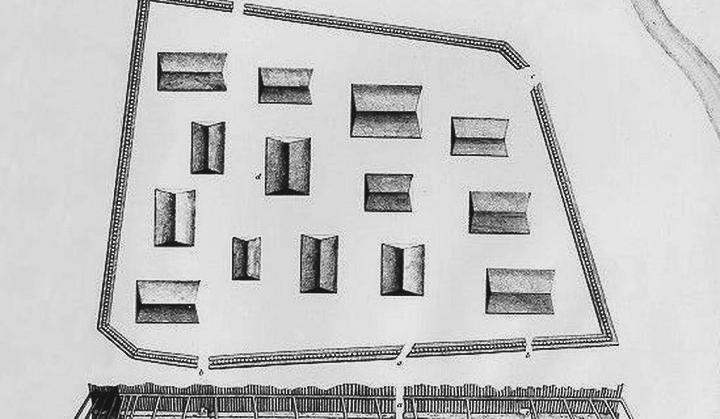

The peninsula where the fort was located on what's now called Baranof Island has long been recognized as a site of historical importance. It was given federal protection by the U.S. government as a monument beginning in 1910. Now a popular tourist attraction—it's a common destination for the region's cruise industry—the park has walking paths lined with Tlingit and Haida totem poles. Much of the seaside park is forested, but the U.S. National Park Service had designated a clearing for the probable location for the fort, which was documented and then razed by the Russians. However, there has not been broad agreement on where exactly the fort was, said Cornell research scientist Thomas Urban, lead author of the new study published in Antiquity. "A number of investigations over the years produced some clues but no definitive answer," Urban says. "Outside of the clearing itself, geophysical surveying is very tedious because most of the peninsula is densely forested." Urban said he was in Sitka to assist in locating burials at a historic cemetery when the park officials first inquired about resuming the search for the fort site. In the 1950s, archaeologists had dug a few trenches and discovered what they thought were rotting pieces of the fort's palisade wall. The site was revisited by an NPS team again from 2005 to 2008 who found cannon balls and other artifacts associated with the battle inside the clearing commemorating the fort. But those researchers could not confirm that this was indeed the correct location of the fort. In the summer of 2019, Urban and study co-author Brinnen Carter, of the National Park Service, scanned large swathes of the park, including areas with thick vegetation, using new technologies. Geophysical tools allow archaeologists to see buried structures without excavating because different features and materials—for example, bricks, postholes, cannonballs, and loose soil—often have different signatures. The footprint of the underground structures Urban and Carter found match the drawings Russians made of the trapezoidal-shaped fort. At around 300 feet long and 165 feet wide, the perimeter of the fort surrounds the modern clearing. Such forts were not part of traditional Tlingit architecture—most of the other fort sites take advantage of natural rock formations—but the building seems to have been an adaptation to deal with conflict with colonizers, says Thomas Thornton, a dean at the University of Alaska Southeast and a researcher affiliated with the University of Oxford. The name for the fort in Sitka, Shís'gi Noow, means sapling fort in English, which hints at an important innovation: the Tlingits learned that more flexible new-growth timbers would better absorb the shock of Russian cannonballs.

The fort "represents a watershed event in Alaska's history," says Thornton, who wasn't involved in the new research but has studied Tlingit history and collaborated on research with the Sitka Tribe. "If we better understand it through archaeology, through oral history, the better off we will be in terms of being informed about this history, which is still quite present in the architecture of Sitka and the relationships that you find in Sitka." The oral histories collected by Tlingit members of the Sitka tribe investigated unsettled aspects of the conflict. Through arduous trial and error, Kiks.adi elder Herb Hope spent years in the late 1980s and 1990s trying to retrace the steps of his ancestors' survival march to determine their route. (He came to the conclusion that they likely took a coastal path.) Hope once said that he was inspired to undertake the project after he saw Kiks.ádi clan members apologizing for their part in the 1804 war. He wanted to dismantle the notion that the Kiks.ádi retreated. "It was a survival march through our own backyard to a planned location," he told a Tlingit conference in 1993. "However the Russians may have viewed the battle at that time and however history may view that battle today, at that time the Battle of Sitka of 1804 clearly showed the rest of the world that the Russian forces in Alaska were too weak to conquer the Tlingit people." Oral histories suggest that up to 900 people took part in that march. The Kiks.ádi moved from campsite to campsite north along the craggy landscape of Baranof Island to reach Point Craven on the neighboring Chichagof Island, where they took over an abandoned fort called Chaatlk'aanoow. From that post they were able to hurt Russian trade by establishing a blockade of Sitka Sound. According to Hope's account: "The blockade became even more effective once the Yankee traders learned of the blockade and sought to exploit it. They set up a trading station across from Chootlk'aanoow on Catherine Island to the south. Even to this day it bears the name 'Traders Bay.' Trader canoes from all over the northern end of Southeast Alaska came to trade with the Yankee traders at Traders Bay." The Tlingit people returned to Sitka in 1821, but would never again have sovereign control of the island. The NPS and Urban currently have no further plans to investigate the fort site, but its identification offers a clearer picture of a short-lived but hugely significant building. And for Urban, the identification of the fort also shows the potential for geophysical investigations in Alaska, which he says have recently been used to find burial sites, the ruins of houses, mammoth bones, and even 10,000 year old campfires. |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||