|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

February 2021 - Volume

19 Number 2

|

||

|

|

||

|

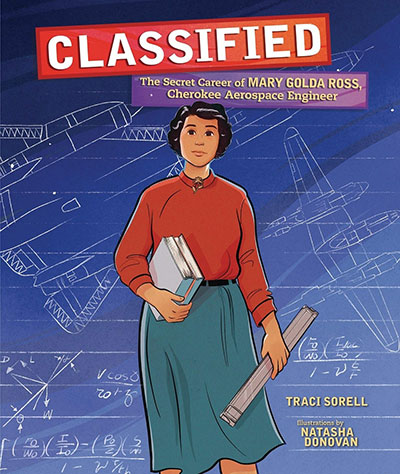

Mary Golda Ross:

The First Native American Aerospace Engineer And Space Race Pioneer

|

||

|

by A Mighty Girl Staff

|

||

When Mary Golda Ross, the first Native American aerospace engineer, began her career at the aerospace company Lockheed during World War II, women engineers were rare and most companies expected them to leave after the war was over to make room for returning men. Ross was such a phenomenal talent, however, that she not only stayed at Lockheed for over 30 years years, she became an integral member of the top-secret Skunk Works program involved in cutting edge research during the early years of the space race. As one of 40 engineers in Lockheed's Advanced Development Projects division, Ross was the only female engineer on the team and the only Native American. Her research was so secret that, even in 1994, she had to be coy with an interviewer about her work: "I was the pencil pusher, doing a lot of research," she said. "My state of the art tools were a slide rule and a Friden computer."

Born on August 9, 1908 in Park Hill, Oklahoma, a small town often called the 'center of Cherokee culture,' Ross was the great-granddaughter of renowned Cherokee Nation Chief John Ross. A talented child, Ross was sent to live with her grandparents in the Cherokee Nation capital of Tahlequah, Oklahoma to attend school. She loved math from an early age, and said that she "didn't mind being the only girl in math class [because] math, chemistry and physics were more fun to study than any other subject." She went on to earn a bachelor's degree in mathematics in 1928 at Northeastern State Teachers' College and a master's degree in 1938 from the Colorado State Teachers College, where she took "every astronomy class they had." During the Great Depression, she taught math and science for nine years in rural Oklahoma schools. On the advice of her father, Ross moved to California in 1941 after the U.S. joined WWII to seek out more work opportunities and was hired as a mathematician by Lockheed in 1942. Initially, she worked on the P-38 Lightning, one of the fastest airplanes at the time that was used extensively during WWII. Her research on the effects of pressure on the fighter plane helped solve problems related to high speed flight and aeroelasticity. The war years involved nearly non-stop work and she recalls that "often at night there were four of us working until 11 pm." Impressed by her work, Lockheed sent her to UCLA following the war for a professional certification in engineering. In 1952, she was invited to join Lockheed's top-secret Advanced Development Projects division, commonly known as Skunk Works, where she worked on "preliminary design concepts for interplanetary space travel, manned and unmanned earth-orbiting flights, the earliest studies of orbiting satellites for both defense and civilian purposes." She also worked on the cutting-edge Agena rocket project, and on preliminary design concepts for flyby missions to Venus and Mars as one of the authors of the NASA Planetary Flight Handbook Volume III. As she once said of her work in an interview, "we were taking the theoretical and making it real." By the time she retired in 1973, she had reached the rank of senior advanced systems staff engineer and had worked on the Polaris reentry vehicle and the Poseidon and Trident missiles.

In celebration of the opening of the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in 2004, then 96-year-old Ross asked her niece to make her a traditional Cherokee dress. The green calico dress was the first traditional dress that Ross ever owned, and she wore it as part of procession of 25,000 Native Americans during the museum's opening ceremony. Ross also left an endowment of $400,000 to the museum upon her death at the age of 99 in 2008. She was proud to be able to contribute to the museum's ability to "tell the true story of the Indian — not just the story of the past, but an ongoing story." In honor of Ross' work, the U.S. Mint's 2019 Native American $1 coin, which is dedicated to American Indians in the Space Program, features an image of Ross on its face. "Her achievements deeply impressed me," says Emily Damstra, the science illustrator who designed the coin. "From the beginning of my design process, before I had anything else worked out, I knew that my design would include a figure of her." Ross would no doubt be thrilled to know that her story is inspiring a new generation of mathematicians and engineers: when asked about women in the space program in the 1960s, she said that women would make "wonderful astronauts" but added, "I'd rather stay down here and analyze the data." |

|||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2021 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2021 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||