|

In Indigenous communities

along the coast, a lively artistic movement plays with tradition

|

|

|

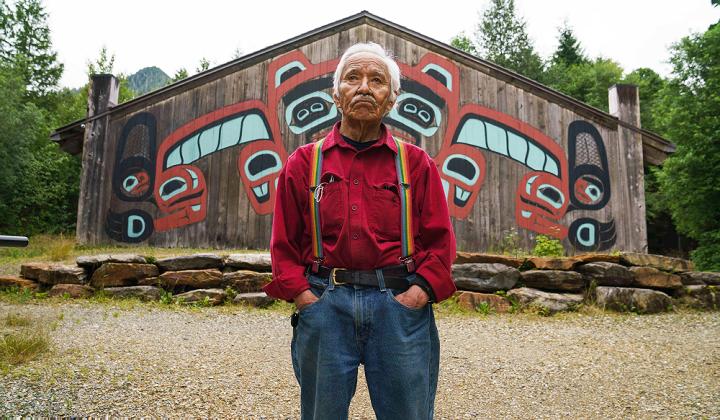

Nathan Jackson, a Chilkoot Sockeye clan leader,

in front of a Beaver Clan house screen that adorns a longhouse

at Saxman Totem Park. The house screen was carved on vertical

cedar planks before it was raised and assembled on the house

front. Jackson, who led the project, found his way back to

his heritage circuitously after a boyhood spent at a boarding

school that prohibited native languages and practices. (Fernando

Decillis)

|

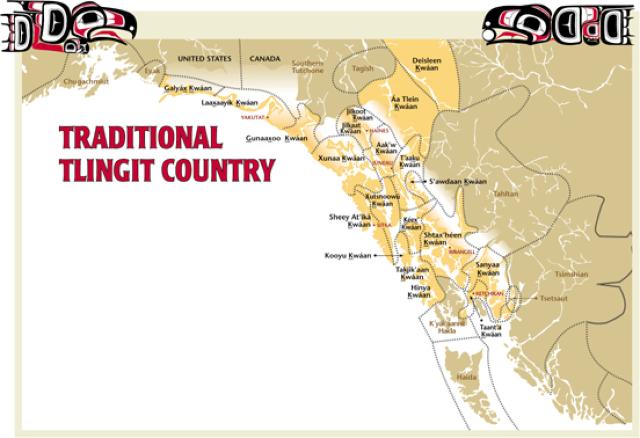

Among the indigenous nations of Southeast Alaska, there is a concept

known in Haida as Íitl’ Kuníisii—a timeless

call to live in a way that not only honors one’s ancestors

but takes care to be responsible to future generations.

The traditional arts of the Haida, Tlingit and Tsimshian people

are integral to that bond, honoring families, clans, and animal

and supernatural beings, and telling oral histories through totem

poles, ceremonial clothing and blankets, hand-carved household items

and other objects. In recent decades, native artisans have revived

practices that stretch back thousands of years, part of a larger

movement to counter threats to their cultural sovereignty and resist

estrangement from their heritage.

They use materials found in the Pacific rainforest and along the

coast: red cedar, yellow cedar, spruce roots, seashells, animal

skins, wool, horns, rock. They have become master printmakers, producing

bold-colored figurative designs in the distinctive style known as

“formline,” which prescribes the placement of lines, shapes

and colors. Formline is a visual language of balance, movement,

storytelling, ceremony, legacy and legend, and through it, these

artisans bring the traditions of their rich cultures into the present

and ensure their place in the future.

|

|

|

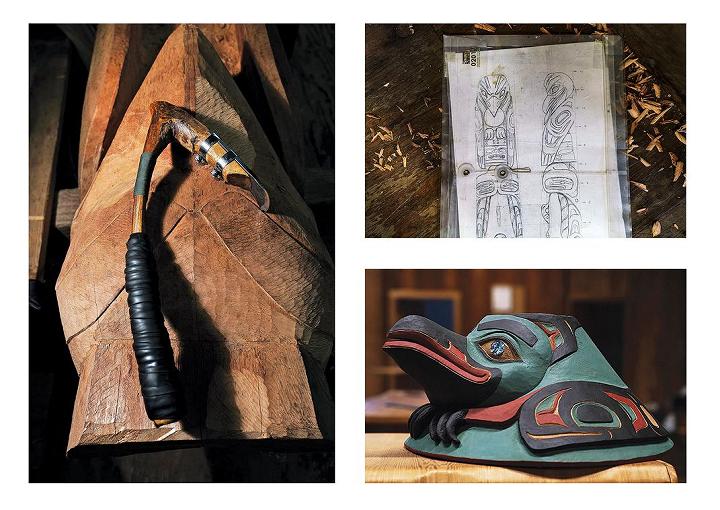

A carver of monumental art, Nathan Jackson

works with a tool pictured below, called an adze. Jackson,

who also goes by Yéil Yádi, his Tlingit name,

carves a cedar panel depicting an eagle carrying a salmon

in its talons. (Fernando Decillis)

|

|

|

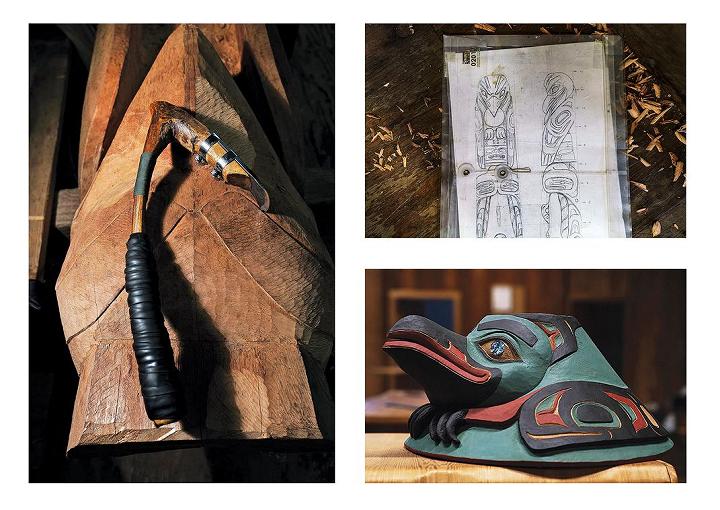

Clockwise from left: Jackson's adze. Above

right, formline designs drawn on paper will be laid out on

a twelve-foot totem pole before carving; a raven helmet, inlaid

with abalone shell. (Fernando Decillis)

|

|

|

|

At the Totem Heritage Center in Ketchikan,

Alaska, Jackson wears ceremonial blankets and a headdress

made from ermine pelts, cedar, abalone shell, copper and flicker

feathers. (Fernando Decillis)

|

|

|

|

Alison Bremner apprenticed with the master

carver David A. Boxley, a member of the Tsimshian tribe. She

is thought to be the first Tlingit woman to carve and raise

a totem pole, a feat she accomplished in her hometown, Yakutat,

Alaska. Now based in Juneau, she creates woodcarvings, paintings,

mixed-media sculpture, ceremonial clothing, jewelry, digital

collage and formline prints. Her work is notable for wit and

pop culture references, such as a totem pole with an image

of her grandfather holding a thermos, or a paddle bearing

a tiny nude portrait of Burt Reynolds in his famous 1970s

beefcake pose. (Fernando Decillis)

|

|

|

|

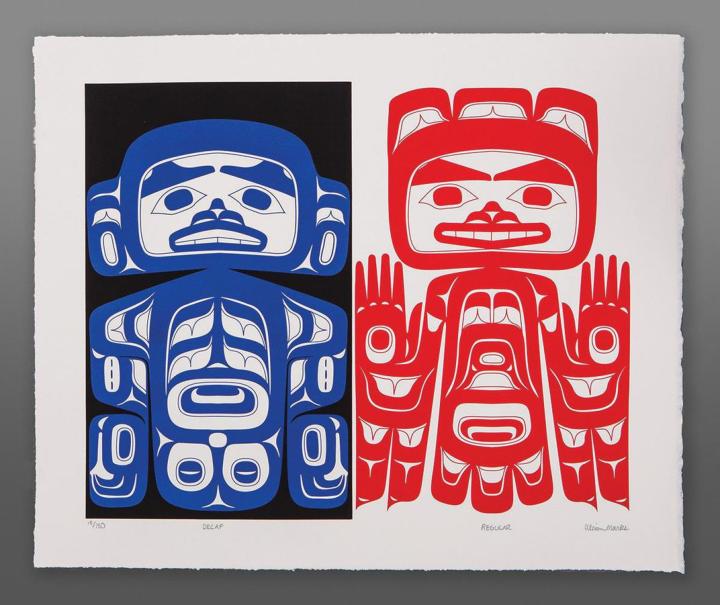

Alison Bremner's silkscreen work titled Decaf/Regular.

(Alison Bremner / Courtesy Steinbrueck / Native Gallery)

|

|

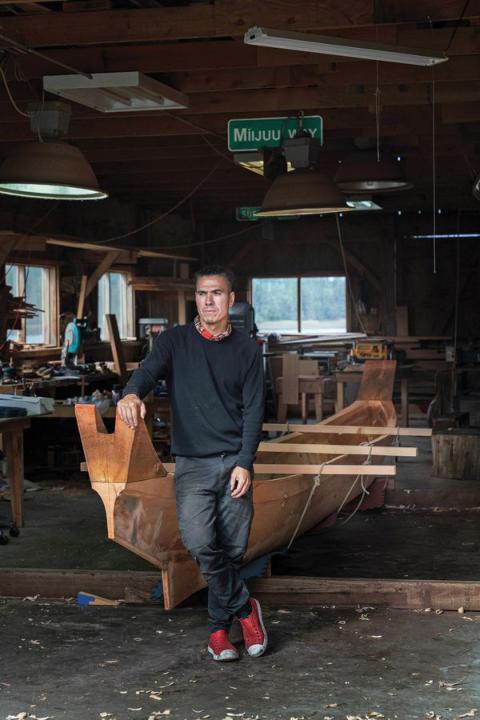

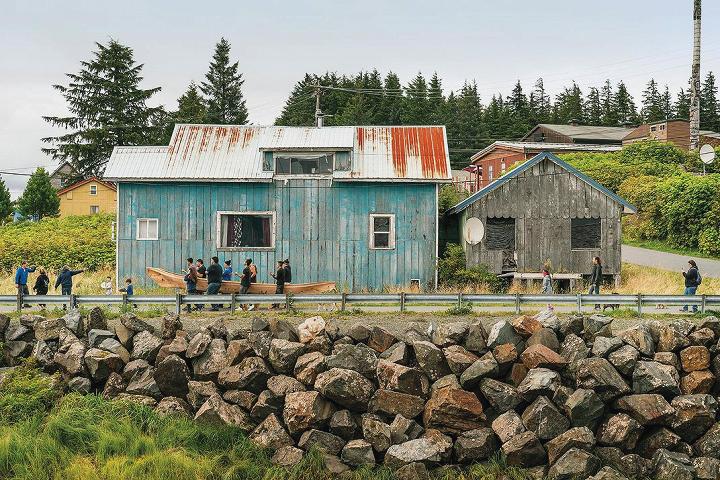

Sgwaayaans, a Kaigani Haida artist, carved

his first totem pole at age 19. Last year, he made his first

traditional canoe, from a red cedar estimated to be 300 years

old. Once the canoe was carved, it was taken outside to a

lot near the Hydaburg River. (Fernando Decillis)

|

|

|

|

|

Clockwise from left: canoe builder Sgwaayaans

and his apprentices heat lava rocks that will be used to steam

the wood of a traditional dugout canoe; the heated lava rocks

are lowered into a saltwater bath inside it, to steam the

vessel until it is pliable enough to be stretched crosswise

with thwarts; more than 200 tree rings in the Pacific red

cedar are still visible with the canoe in its nearly finished

form; Sgwaayaans strategically inserts the crosswise thwarts

and taps them into place with a round wooden mallet to create

the desired shape. (Francisco Decillis)

|

|

|

|

Haida community members then carried the canoe

back to the carving shed. Historically, the Haida were famous

for their giant hand-carved canoes; a single vessel was known

to carry 60 people or ten tons of freight. (Francisco Decillis)

|

|

|

|

Lily Hope, a designer of Chilkat and Ravenstail

textiles, lives in Juneau with her five children. She is seen

weaving Tlingit masks during the Covid-19 pandemic. Hope is

well known for her ceremonial robes, woven from mountain goat

wool and cedar bark, and often made for clan members commemorating

a major event like a birth, or participating in the mortuary

ceremony known as Ku.éex, held one year after a clan

member’s death. An educator and a community leader, Hope

also receives “repatriation commissions” from institutions

that return a historical artifact to its clan of origin and

replace it with a replica or an original artwork. (Fernando

Decillis)

|

|

|

|

Tlingit masks woven by Lily Hope during

the Covid-19 pandemic. (Fernando Decillis)

|

|

|

|

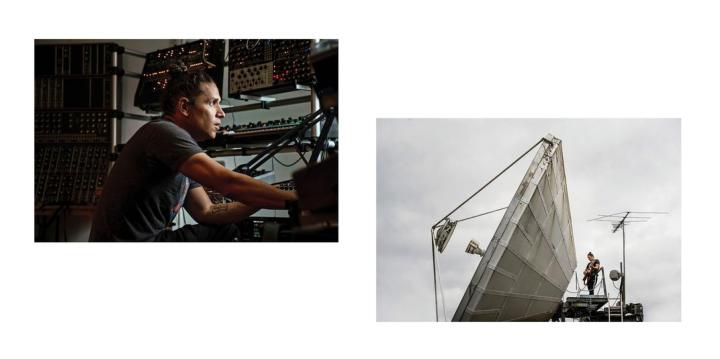

Nicholas Galanin, a Sitka-based artist and

musician, draws on his native heritage to create conceptual

artworks that diverge from tradition while also commenting

on it. Examples include ceremonial masks carved from anthropology

textbooks and a totem pole covered in the same wallpaper as

the gallery wall on which it hangs, causing it to nearly disappear.

(Fernando Decillis)

|

|

|

|

Architecture of Return, Escape (Metropolitan

Museum of Art), Nicholas Galanin's map of the Met on a deer

hide. It shows in red paint where the “Art of Native

America” exhibition’s 116 artworks are located and

suggests a route for them to “escape” from the museum

and “return” to their original homes. (Fernando

Decillis; Courtesy the artist and Peter Blum Gallery, New

York, 2020)

|

|

|

|

Tsimshian culture bearer David A. Boxley with

his grandson Sage in his carving studio in Lynwood, Washington.

An oversize eagle mask used for dance ceremonies and performances

sits on the workbench. (Fernando Decillis)

|

|

|

|

David A. Boxley carefully restores a cedar

house pole that commemorates his journey as a father bringing

up his sons David Robert and Zachary in the Tsimshian culture.

(Fernando Decillis)

|

| About the Author: Fernando Decillis works primarily in the

United States and in Colombia, as both an editorial and advertising

photographer. His clients have included Coca-Cola and Reebok,

and his work has appeared in Vanity Fair and Bloomberg Businessweek

among others. Read

more articles from Fernando Decillis |

Alaska

Native Knowledge Network (ANKN)

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network (ANKN) is an AKRSI partner designed

to serve as a resource for compiling and exchanging information

related to Alaska Native knowledge systems and ways of knowing.

It has been established to assist Native people, government agencies,

educators and the general public in gaining access to the knowledge

base that Alaska Natives have acquired through cumulative experience

over millennia. Anyone wishing to participate in the Alaska Native

Knowledge Network or contribute to the development of the resources

in this knowledge base is encouraged to contact us at (907) 474-5897,

or email fyankn@ankn.uaf.edu.

Our offices are located at UAF's Bunnell Building, Room 117 in Fairbanks,

Alaska. We welcome you to drop by in person and browse our curriculum

libraries or check out our newest publications.

http://www.ankn.uaf.edu/index.html

|