|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

NovemBER 2020 - Volume

18 Number 11

|

||

|

|

||

|

'Jim Crow, Indian

Style': How Native Americans Were Denied The Right To Vote For Decades

|

||

|

by Dana Hedgpeth - The

Washington Post

|

||

|

'They're the only ethnic

group in America that had to give up their culture to get the right

to vote.'

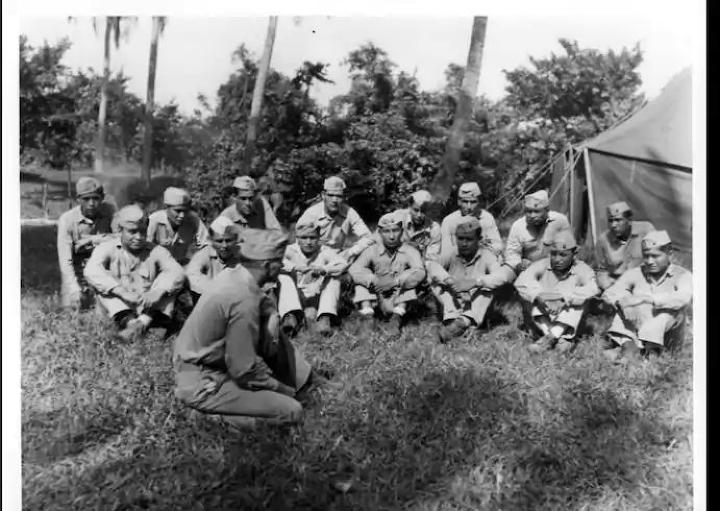

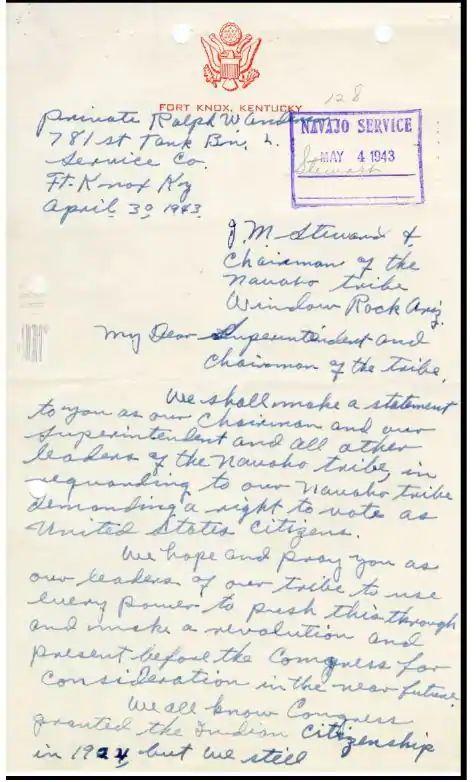

Pvt. Ralph W. Anderson, a Navajo who had served in the U.S. Army in World War II, had a question about the U.S. policies that kept him and other Native Americans from voting. In his May 4, 1943, letter from Fort Knox, Ky., he wrote: "We all know Congress granted the Indian citizenship in 1924, but we still have no privilege to vote. We do not understand what kind of citizenship you would call that." He went on: "We feel that we should be recognized as a full citizen of the United States of America. … Every [Navajo] that can read and write should have privileges to vote in all elections. That is the way it should be according to the Constitution of [the] United States of America." "Hundreds of young [Navajo] boys beside us took the oath of allegiance to the flag and the country whom they are now in the armed forces and [scattered] all over the world fighting for their country just like anybody else." Anderson signed the letter, "Very truly yours, From the Navajo Soldier Boys." His letter, Native American political experts and historians said, offers a window into the decades-long, complicated fight to vote that involved dozens of lawsuits, Jim Crow-style tactics, and racist efforts to deny the ballot to American Indians. Even now, Native Americans face barriers to voting due to a host of issues, including not having the required voter identification, homelessness, lack of traditional mailing addresses, and unequal access to in-person voting, according to Jacqueline De León, a staff attorney for the Native American Rights Fund. Even with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924 that technically gave Native Americans the right to vote, historians said, tribal members were still shut out from voting for decades. For tens of thousands of Native Americans who served in the two world wars, it was especially disappointing because they were denied their rights in a country they'd fought for and that was built on land their ancestors had inhabited for centuries. "It sends a message that you're not a citizen. You're not human," said Debbie Nez-Manuel, who is a citizen of the Navajo Nation and was the first Native American from Arizona elected to the Democratic National Committee. "That message came across loud and clear, even today." "When you serve the U.S. government you're thinking, 'I gave up my life,'" Nez-Manuel said. "'I sacrificed. Where is the reciprocity?'" The tale of Native Americans trying to get the right to vote is linked to their citizenship. Though some Native Americans can trace their ancestral roots back more than 30,000 years on land that is now the United States, they weren't guaranteed — or given — citizenship, denying them the right to vote. "For the first 150 years of the existence of the U.S., Native Americans were not allowed to vote," said De León, who is an enrolled member of the Isleta Pueblo in New Mexico. And many Native Americans didn't see the need to push for citizenship or the right to vote in the 18th century. But as settlers and conquerors pushed them from their land, it became clearer to Native Americans that they'd have to become involved in the U.S. political system to save their lands and culture. Still, some were reluctant because they worried that would harm their tribal sovereignty and rights. "Being part of a tribe is crucial to being Indian, and it means you're part of a separate nation, a separate government," said Dan McCool, a professor of political science at the University of Utah and author of the book "Native Vote: American Indians, the Voting Rights Act, and the Right to Vote." "They wanted to be separate from America from when white people first arrived," McCool said. But that proved impossible. As Native Americans were pushed from their tribal lands in the 19th century, citizenship was dangled like a carrot. In some cases, Native Americans were granted citizenship in exchange for their land. One 1855 treaty with the Wyandot Indians, who were pushed from the upper Great Lakes area to Oklahoma, demanded all of the tribe's land and that the "tribe shall be dissolved and terminated" in exchange for becoming "citizens of the United States." Other laws and policies prohibited Native Americans from becoming citizens because they were considered "subjects" or "wards" of the government. In 1856, U.S. Attorney General Caleb Cushing wrote: "The fact, therefore, that Indians are born in the country does not make them citizens of the United States. The simple truth is plain, that Indians are subjects of the United States, and therefore are not, in mere right of home-birth, citizens of the United States." By the early 1900s more than half of Native Americans in the country had become U.S. citizens, but they'd done it at a huge sacrifice, having given up at least 90 million acres through treaties, allotments or forced statutes. In many instances, they were offered citizenship if they assimilated. They had to learn to read and speak English to be granted citizenship. In Minnesota, the state's constitution had a "cultural purity test" that prohibited Native Americans from voting unless they "adopted the language, customs, and habits of civilization." Native Americans are the "only ethnic group in America that had to give up their culture to get the right to vote," according to McCool. Even with the 14th and 15th amendments to the U.S. Constitution, which granted citizenship and the right to vote to African Americans, the government interpreted those laws so they excluded Native Americans. In the 1860s, when citizenship was extended to formerly enslaved people born in the United States, Michigan Sen. Jacob Howard declared: "I am not yet prepared to pass a sweeping act of naturalization by which all the Indian savages, wild or tame, belonging to a tribal relation, are to become my fellow-citizens and go to the polls and vote with me." Even so, Native Americans enlisted in the military during World War I. "Ironically, they were fighting for freedoms abroad that they did not possess at home," wrote Willard Hughes Rollings, a historian on Native Americans at the University of Nevada, in an article called "Citizenship and Suffrage: The Native American Struggle for Civil Rights in the American West, 1830-1965. At the end of the war, Congress gave citizenship to Native American veterans who had been honorably discharged. But when Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924, many Native Americans still faced what historians called "Jim Crow, Indian-style." Whites used tactics to intimidate Native Americans and prevent them from voting much like efforts used in the South against African Americans. To keep Native Americans from voting, states refused to put polling places near reservations or tribal communities, and required Native Americans to pass literacy or English language tests or pay poll taxes. "We became citizens, but it was a partial citizenship," said David E. Wilkins, a citizen of the Lumbee Nation in Pembroke, N.C., who teaches Native American law and policy at the University of Richmond in Virginia. "Our race still determined that we were less than full citizens." One Arizona court ruled against Native Americans being allowed to vote because they were considered "wards of the government." In its decision, the court wrote, "no person under guardianship, non compos mentis, or insane shall be qualified to vote at any election." During World War II, thousands of Native Americans served overseas, then faced discrimination at home. When some of the famous Navajo Code Talkers were denied the right to vote, it helped focus more attention on the racial disparities Native Americans faced in voting.

Anderson, the Army private, who had questioned why he was denied the right to register to vote in Arizona, got a response from General Superintendent J.M. Stewart, who oversaw the Navajo reservation at Window Rock. Stewart wrote, "There should be no question that you, who are making such great sacrifices for your country, should have some voice in how it should be governed. Your patriotism is not denied, your devotion to duty is beyond question and in certain phases of warfare, the Navajo has no equal. With such a record, there can be no denial that you are entitled to the same right of suffrage as other citizens." It took until the 1960s and the passage of the Voting Rights Act for Native Americans to get the right to vote in every state, with Utah and Maine being among the last to recognize their full voting rights. But the legacy of being disenfranchised for so long persists. Experts estimate there are roughly 1 million American Indians who are not registered to vote, making them what one voting rights advocate calls a "potent but untapped political force." Even now Native American elders still sometimes "tell younger people not to vote" in U.S. elections, said De León, who helped McCool author a NARF report called "Obstacles at Every Turn," which was published in June and looked at the barriers Native Americans have faced in voting. "It has to do with the humiliation they were subjected to," De León said, "and the idea that you'd have to give up your Indian culture to vote." Read more Retropolis:

|

||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2020 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2020 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||