|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

August 2020 - Volume

18 Number 8

|

||

|

|

||

|

Perspective: Grandma

Cele, The Unknown Ojibwe Suffragette

|

||

|

by Mary Annette Pember

- Indian Country Today

|

||

In praise of the bold, outspoken

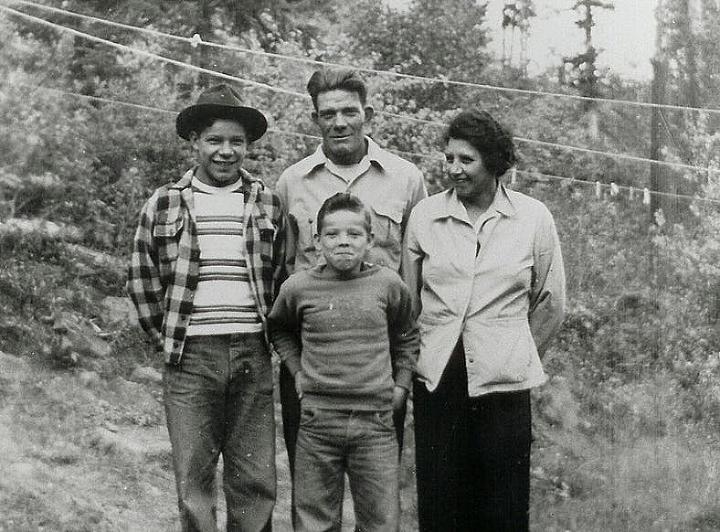

and frequently overlooked Native women who fought for the vote As we recognize the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, I think of my Grandma Cecelia Rabideaux, known as Cele to family and friends. Cele died in the 1950s before I was born; she was only 57 years old. Part of my family's often vaguely shameful past, memories of her are seldom spoken aloud. Most commonly, I've heard her described as a loudmouth, a troublemaker who used foul language and most certainly was not a lady as measured by the oppressive standards of 1920s-era America. But somewhere in between the lines of these scanty memories is a mysterious air of grudging respect and even awe. That whiff of juicy backstory, however, has remained elusive until this year. I learned recently that Cele was one of the founders of the country's first Indian League of Women Voters in 1924, the same year in which Native Americans were declared citizens of the United States. Cele was an 18-year-old single mother in 1920 when women gained suffrage. Educated by Catholic nuns at St. Mary's Indian boarding school, her curriculum was surely imbued with civilization-era lessons intended to assimilate Natives into mainstream society. During civics class, she would have learned about the democratic process and citizens' rights and duties to participate. The crafters of the 1819 Civilization Act Fund intended that Native people abandon their traditional ways for a hard-working servile role in America's new society. Surely, given the racial and gender social norms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, White male politicians and leaders in the federal government never envisioned the civilization policies would inspire Native people, especially women, to rise up and claim equal access to rights, citizenship and voting. But as professor of American studies Brenda Child of the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation notes, traditionally Ojibwe women inhabited a world in which the Earth was gendered female. Prior to the arrival of European settlers, Ojibwe women lived in a society that valued an entire system of beliefs associated with women's work, not just the product of their labor. Early on, Native women influenced the women's rights and suffrage movements. Although only recently acknowledged by writers of mainstream history, Native women such as the Haudenosaunee inspired White women's rights activists Matilda Joslyn Gage, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Traditionally Haudenosaunee women had a great deal of political authority; they participated in all major decisions and had veto power over declarations of war. It was women who chose the chiefs. As described in the Washington Post, Stanton had frequent contact with Haudenosaunee women near her home in Seneca Falls, New York, the site of the now-famous Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention held in 1848. "Indigenous women have had a political voice in their nations long before White settlers arrived," Sally Roesch Wagner, one of the first U.S. doctorates to work in women's studies, told the Washington Post. For Indigenous women, however, women's rights and voting rights were tools to be used for survival and defending against the dispossession of land and resources. "For Native women, women's rights have never been separate from Native rights," Child says. Thus was the case with Grandma Cele. In 1926, a newly minted U.S. citizen, voter and chairman of the first Indian League of Women Voters at age 24, Cele used her officially recognized legal power to advocate for her brother Paul Moore. I stumbled across Grandma Cele's name completely by accident as I pored over 1920s-era records of congressional hearings dealing with misuse of Native trust and treaty funds and corruption within the Bureau of Indian Affairs. My research was part of an investigative journalism project examining the misuse of Native funds to pay for tuition in Catholic Indian boarding schools. It was late at night and my eyes were burning from hours of staring at the tiny print when the name "Cecelia Rabideaux" grabbed my attention. Initially I thought my tired eyes were deceiving me. Here was the name of the woman my mother hated, the bad mother who abandoned her and her four siblings when my mother was a child. Cele abandoned the family after her first husband, my grandpa Joe, beat her nearly to death. With little in the way of legal, economic or social protection for Native women in those days, Cele was placed at an untenable moral impasse, physical survival or motherhood. She chose survival; my mother never forgave her and seldom spoke her name. Cele married a White man and started a new family. I was surprised to see Cecelia Rabideaux, the long-vilified woman of my family memories, described by James Frear, representative for Wisconsin's 9th District, as a "responsible woman" and chairman of the League of Women Voters. Frear read her notarized statement before the 1926 Senate Committee on Indian Affairs as an example of corrupt judicial practices by Bureau of Indian Affairs reservation superintendents.

She'd written to Frear for help, describing how her brother Paul was arrested without warrant or due process and jailed 70 miles away from the Bad River Reservation, on the Lac du Flambeau reservation. Like many Native people during that era, Uncle Paul was arrested and incarcerated at the whim of a reservation superintendent. Grandma Cele took the train to Lac du Flambeau and confronted the superintendent, insisting she be allowed to see Paul. She found him languishing along with several other Native men and women in a tiny, filthy jail cell with a ball and chain fastened to his ankle. Eventually Wisconsin Gov. John Blaine carried Cele's protest all the way to then-President Calvin Coolidge. Coolidge wired the superintendent with the recommendation that Uncle Paul be "permitted to escape." Uncle Paul finally walked free. Greater surprises about Cele came later. According to the archives of the Wisconsin League of Voters, the village of Odanah on the Bad River Ojibwe Reservation is the birthplace of the first Indian League of Women Voters, established in October 1924. Ellen Penwell, membership and events manager of the League of Women Voters, forwarded links to the organization's original newsletter, "Forward." In November 1924, League president Belle Sherwin wrote in "Forward":

In the November 1929 issue of "Forward," the following appeared, written by an uncredited author:

According to Cathleen Cahill, associate professor of history at Penn State College, it was the work of Native women such as Cele and members of the Indian League of Women Voters who aided in forwarding the Wheeler-Howard Act of 1934, which ended federal allotment of Native lands and stressed self-governance. Cahill is the author of the upcoming book "Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement" and has written extensively about the history of Native women in politics and government. Like citizenship and voting rights for Native Americans, some states were slow in ratifying the 19th Amendment. Wisconsin was the first in 1920; Mississippi, however, didn't officially ratify the 19th Amendment until 1984. Although the Civil Rights Act of 1965 guarantees the right to vote regardless of race, Native people continue to face efforts to suppress their votes, such as the Ballot Interference Prevention Act in Montana. I was surprised to learn that after she married her second husband and moved to Idaho in the early 1930s, Grandma Cele didn't pursue her political activism. My Uncle Russ, her one remaining son, has no recollection of Cele expressing any interest in politics after the move to Idaho. He does recall, however, that she always carried a hatchet under the front seat of her 1934 Chevy Coupe in case anyone messed with her. Nearly 100 years later, as I learn more about Grandma Cele's remarkable past, her life stands as an allegory for Native women's ongoing battle and advocacy for family, land, resources and physical survival. Despite her mistakes, Cele never abandoned her stubborn belief that Native people deserved better, that we too are entitled to the benefits of the democratic process. I like to think she passed along this burning conviction to my mother, Bernice, who despite remaining estranged from Cele her entire life, was fiercely involved in politics and voting rights as a member of several Democratic women's groups. "I'm sure there were many Native women like your grandma who advocated for women's and voting rights whose history we may never know," says Cahill. Her upcoming book includes the histories of more well-known Native suffragists such as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, also known as Zitkala-Sa of the Yankton Sioux tribe and Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, laudable women deserving of praise. But, on this centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment, let us also praise all the obscure loudmouth Native women like Cele who demanded justice and equity for their people. Although usually overlooked by the White man's history books, they stand tall and brave beyond belief. They blazed the trail for us all.

Mary Annette Pember, a citizen of the Red Cliff Ojibwe tribe, is a national correspondent for Indian Country Today. |

||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2020 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2020 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||