|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

August 2020 - Volume

18 Number 8

|

||

|

|

||

|

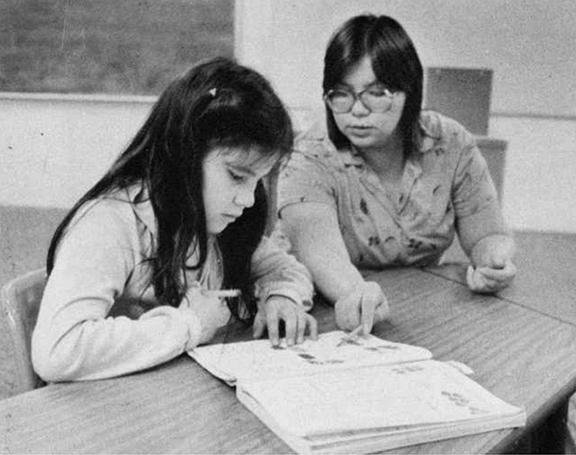

Why AIM Started The

Heart Of The Earth Survival School

|

||

|

by Jon Lurie - MinnPost

|

||

In 1970, the American Indian Movement (AIM) declared its intention to open a school for Native youth living in Minneapolis. AIM had identified the urgent need for Indigenous children to be educated within their own communities. Two years later, Heart of the Earth Survival School opened its doors, providing hope to Native families whose children had endured the racial abuse prevalent in the Minneapolis public schools. In the 1960s and early 70s, due in part to discrimination experienced within the public schools, the dropout rate among Native students in the Twin Cities hovered between 60 and 80 percent. This led to an even greater crisis: the widespread removal of “truant” children from their homes by the social welfare agencies of Ramsey and Hennepin Counties. Most of these young people, in violation of international law, were placed outside of Native communities, with white foster parents. According to the United Nations, taking children from their families and placing them in outside communities is a form of genocide. Whether the social workers did this to arrest the transmission of Native culture or not, the effect of these removals was deeply damaging. In 1970, AIM announced its aspiration to end the practice. Its plan was to open a “survival school,” an alternative to public and Bureau of Indian Affairs schools that would place Indigenous culture at the center of its curriculum. AIM, which had formed just two years prior, lacked the resources to open a school; it would not be long, however, before necessity forced it to act. In 1971, Patricia and Jerry Roy, whose three sons attended Minneapolis Public Schools, approached AIM, desperate for help. The White Earth Ojibwe family was under siege by Hennepin County Social Services, who claimed the boys were truant. The Roys had made the decision to homeschool after their sons were repeatedly victimized at school. The boys reported having their long hair pulled and being called derogatory names. They refused the school officials’ order to cut their hair. AIM leaders Dennis Banks and Clyde Bellecourt agreed to accompany the Roys to a court appearance. Banks and Bellecourt furiously challenged Judge Lindsay Arthur to stop stealing Native children from their homes. Arthur had heard of the AIM leaders, and during a discussion in his chambers, he admitted he was sympathetic to their plight, but said he had no choice but to remove truant children. After a heated argument, Arthur agreed to send Native kids to AIM, so long as it could provide them an alternative to public school. In January 1972, AIM members did just that when they welcomed eight students, including the three Roy boys, to Heart of the Earth Survival School. Opened in AIM’s Minneapolis office without a penny spent, the school was austere in the extreme. Students from that first class recall a basement classroom with a single bare lightbulb, cockroaches crawling on the walls, and a toilet that wouldn’t stop flushing. There was one old blackboard, a single piece of chalk, and one pencil for the students to share. What the school lacked in resources, it made up for in vision. Unlike the public schools, which taught a Euro-centric perspective, Heart of the Earth’s vision included the restoration of vanishing knowledge like fishing and hunting skills, wild rice gathering, maple syrup harvesting, and Indigenous languages. Heart of the Earth’s educational approach was largely forged by Ona Kingbird, a young, traditional Anishinaabe who infused the survival school with Indigenous curricula. For eighteen months Kingbird worked without pay, until the school located the funding to pay her. Heart of the Earth’s funding came from the last place AIM expected to find it. In the summer of 1972, the Congress of the United States passed the Indian Education Act, providing federal funds for American Indian and Alaska Native education. The act was a boon for Heart of the Earth, as it allotted funding for each student at the struggling school. As its ranks swelled with children referred by the courts, the school was forced to move twelve times in its first three years. Government regulators continually shut down Heart of the Earth for infrastructure deficiencies, such as a shortage of windows, lack of a playground, and insufficient bathroom facilities. In 1975, Heart of the Earth finally found a permanent home when it purchased the campus of United Methodist Church in Minneapolis’ Dinkytown neighborhood. Heart of the Earth developed its own traditions, providing a cultural and spiritual framework for its students. Every Monday morning, for example, the entire community would gather to pray and sing around the drum. The ceremony was repeated every Friday before the students went home for the weekend. By at least one metric, the school was a resounding success: over its thirty-five years of existence, Heart of the Earth graduated more Native students than the Minneapolis Public Schools combined. In 2008 Heart of the Earth’s executive director, Joel Pourier, was investigated for fraud, and the school was forced to close. Pourier eventually pleaded guilty to embezzling nearly $1.4 million and was sentenced to a ten-year prison term. MinnPost is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization whose mission is to provide high-quality journalism for people who care about Minnesota. |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2020 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2020 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||