|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

March 2020 - Volume

18 Number 3

|

||

|

|

||

|

As A Coronavirus

Pandemic Sweeps the World, American Indian Communities Turn To One

Another, Teachings

|

||

|

by Lynda V. Mapes -

Seattle Times environment reporter

|

||

Tribal communities know death by pandemic. As history threatens to repeat itself with the menace of the novel coronavirus, tribal communities are turning to their teachings and one another to protect themselves amid what they call a near total failure of federal resources to help, despite solemn promises in treaties. No one is waiting in these communities for someone else to come to the rescue. Response to the threat of the virus by tribal governments and health care providers has been swift and aggressive. Tribal governments are sovereign in their territory, with broad emergency powers — and they are using them. States of emergency have been declared at multiple reservations, enabling tribal governments to spend funds, restrict gatherings, close their borders to outsiders, quarantine tribal members in their homes and even postpone elections. It was big news earlier this month when Gov. Jay Inslee restricted gatherings to 250 people in Washington. But some tribal governments, such as the Port Gamble S’Klallam on the Kitsap Peninsula, had already gone further, banning gatherings of more than 10 for at least 90 days. Such extreme measures are necessary, tribal leaders say. The Makah Tribe and Lummi Nation enacted shelter in place ordinances for their citizens, and the Yakama Nation followed suit Monday night. There is no time — and not a resident — to lose. Their actions come against a backdrop of a federal government response that so far has set aside $40 million for tribes, tribal organizations and urban Indian health programs to battle the coronavirus. Not nearly enough, health experts say. Nor is there a clear path for that money to reach tribal health programs. “That is a drop in the bucket,” said Abigail Echo-Hawk, a Pawnee tribal member and chief research officer for the Urban Indian Health Institute, the research division of the health board. “We are at the epicenter of what has happened. And there isn’t a mechanism to get that money into Indian Country in urban and rural areas.”

The health board is one of 41 urban Indian health programs around the country and serves about 6,000 people a year in Seattle and King County. Yet by mid-March the facility has just three coronavirus test kits on hand to deal with the pandemic. “We don’t have the capacity to test any longer,” Esther Lucero, a Dine´ tribal member and chief executive officer of the Seattle Indian Health Board said last week. Whether the declaration of a national emergency by the president would change that was unknown. Like so many other things. “We still don’t have the supplies. Despite what everyone is saying. We have staff capacity but not the supplies,” Echo-Hawk said. “I am angry. Are we trying to address this illness or not?” An offer of 200 additional tests for the virus from the Federal Emergency Management Agency late Friday came with so many unacceptable strings attached that it was no offer at all for a front-line community health program serving people of color, Lucero said. Finally, over the weekend, Public Health – Seattle & King County provided 200 tests expected to arrive Monday. Unlike with FEMA, the board can use its own lab to process the tests, and communicate the results to its own patients — instead of sending them to a national call center. But resources remain woefully lacking to provide a true public health response in the crisis, identifying hot spots and following up with wraparound care, Lucero said. Meanwhile, a loss of clinical providers identified as high risk for the virus, in addition to appointment cancellations, will blow a $734,922 hole in the health board’s budget this month, even as administrative costs are piling up, health board officers wrote in a March 13 letter to the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services. In tribal communities, the people within their borders aren’t just residents, they are family. The duty to protect goes beyond civil and legal jurisdiction. It follows an older and higher law learned long ago when these communities first faced a threat they could not see. Beginning in the 1770s — maybe earlier — outbreaks of infectious diseases, including smallpox, influenza and measles, scythed through Native tribes of the Northwest Coast. Disease killed an estimated 80% of the Native population within 100 years of their first contact with whites, according to historian Robert Boyd, author of the book “The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence,” a history of infectious diseases and population decline among Northwest Coast Indians from 1774 to 1874. So devastated were tribal villages by diseases that in many instances few survived to bury the dead, who were simply left where they fell. Their remains were looted, washed away or scattered. The carnage on the coast was a continuation of the march of death across the continent. The arrival of newcomers in the Americas “was followed by possibly the greatest demographic disaster in the history of the world,” writes geographer William Denevan, emeritus faculty at the University of Wisconsin at Madison in “The Native Population of the Americas in 1492.”

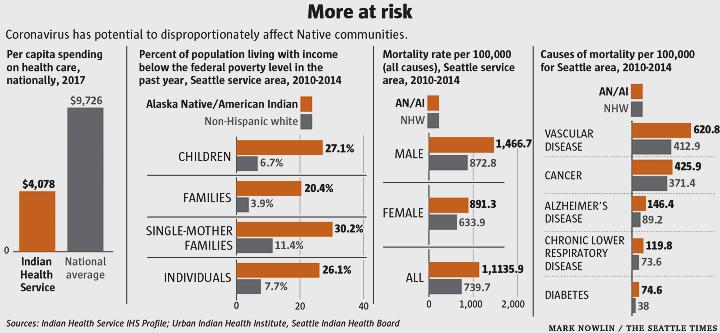

In treaties with the federal government signed by tribal leaders all over the country, as in Washington, one of the promises in exchange for ceding title to their territories was health care for their people. It is a broken promise. Health care for Native people is chronically underfunded by the federal Indian Health Service. Even before the new coronavirus showed up, in Seattle and beyond, Indian and Alaska Native people already faced higher mortality rates and underlying health risks, from diabetes to respiratory diseases. “There is a possibility of disproportionate impact in our communities, because of historic suppression and repression,” Echo-Hawk said. “We cannot allow for that disproportionate impact to happen.”

The Seattle Indian Health Board quickly put together fact sheets and protocols for other Native health providers across the country on its web site, and is advocating to get more resources to Indian people. “We are incredibly resilient. We have our own way of caring for our relatives and our most vulnerable populations,” Lucero said. But now even the basics, such as an adequate public health response, are lacking from the federal government in the middle of an emergency, Echo-Hawk said. Difficulty in a time of need is nothing new: Nationwide, urban Indian health programs serve the more than 70% of American Indian and Alaska Native people living in urban areas, but are allocated less than 1% of the Indian Health Service budget. The agency needs to be fully funded to adequately serve both tribal governments and urban Indian health programs, Echo-Hawk said. During this time of need, even as so many others have shut their doors, The Chief Seattle Club, which serves urban Indians and Alaska Natives, many of whom are experiencing homelessness, is continuing its daily hot breakfasts, but with half the seating to maintain safe social distance, and giving out sack lunches. Serving more than 80,000 meals a year is just part of what the Pioneer Square nonprofit does to help people who often have nowhere else to go.

The club during the pandemic is still open every day, so people can get their clothes washed and take a hot shower. The day center served an average of 116 people every day from March 1-18. That is despite having to temporarily suspend other services, including health care, mental health, employment, public benefits, substance-abuse treatment, legal aid and traditional wellness. Tribal communities have long had teachings, passed from one generation to the next, to keep themselves and their relatives healthy and safe — teachings they are continuing to rely on now, as the novel coronavirus cuts a swath through daily life. Reaching deep into the mossy cloak on the big leaf maple, Elena Prest felt for the juicy root of the fern, pulling it free. Gathering this traditional medicine is part of how Prest, a Skokomish tribal member, stays healthy, not only now, during the emergency of the coronavirus sweeping the world, but always. Gathering these medicines is a practice and a teaching, a way of life that is keeping this tribal community strong even at a time of emergency, said Kimberly Miller, also a Skokomish tribal member. She gathered tender green shoots of nettles and tight green curls of fiddlehead ferns, both full of vitamins and tonic juices. But some of the strongest medicine in Indian Country is the love for one another. In many tribal communities, the hardest thing right now is the need to stay apart. What could be more antithetical to being part of a tribe? “Social distancing, that is a new term here,” said Lawrence Solomon, chairman of the Lummi Indian Business Council, which has declared a public-health emergency on the reservation and enacted a quarantine ordinance, ordering tribal members to stay home, with some exceptions. “When we see our elders, we want to give them a hug or shake hands, and [now] it’s fist bumps and elbow bumps and not even visiting. Try to avoid seeing your elders — that doesn’t sound right at all.” The tribe is working to set up a field hospital in a fitness center on the reservation, with up to 20 beds to care for Native people who are not acute cases, and to take pressure off the hospital in Bellingham. “We saw this coming, about the hospitals becoming overtaxed, and we thought, ‘Why not just take care of our people ourselves?’ ” said Dakotah Lane, medical director for the Lummi Nation, which got an early start on preparing for the virus. The teachings from the past are keeping the people strong, even as the world changes seemingly by the hour. “We have been around this for a long time, we hear the stories about the smallpox,” Solomon said. “We made it through. People have that sense of pride that it will be tough, but we will make it through. We remember who we are.”

Ron Allen, chairman of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe and chairman of the Washington Indian Gaming Association, said the virus already has been an economic hit for tribal governments that fund their operations partly with revenues from tribal government-run casinos. Many casinos have temporarily shut down to protect their employees and the public — while still providing full pay and benefits. Closing down is not only an economic hit or matter of disruption. Tribal communities have deep traditions of welcoming visitors and hosting. Shutting doors, even when it is necessary, sits uncomfortably in tribal cultures. “When Lewis and Clark came through on their return visit, we welcomed them,” said Chuck Sams, communication director for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, referring to the Corps of Discovery and their 1806 journey eastward. The tribe has always welcomed visitors in their territory and yet recently shut the doors to its casino in Pendleton, Oregon. Tribal leaders canceled the tribe’s weeklong basketball tournament, the 33rd annual, which always draws thousands of visitors. General council meetings, where elections were to be held for tribal council positions, have been put off all over the region, including at Suquamish, Port Gamble S’Klallam, the Tulalip Tribes and Umatilla. At Puyallup, the House of Respect elders home terminated all visits, including by family, in order to protect their elders. Yet instinct and teachings align to still embrace the local community beyond the reservation. The Tulalip Tribes shuttered their casino and that day donated all the food on hand at its restaurants — nearly 3,000 pounds of fresh meat, produce and baked goods — to the local food bank. “This is a scary time for our people and our nation,” said Terry Gobin, chairwoman of the Tulalip Tribes Board of Directors. “We will continue to move forward in the best way possible with the information we have. We pray that our people stay safe and healthy. We will get through this together.”

Seattle

Indian Health Board Chief

Seattle Club |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2020 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2020 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||