|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 2018 - Volume

16 Number 12

|

||

|

|

||

|

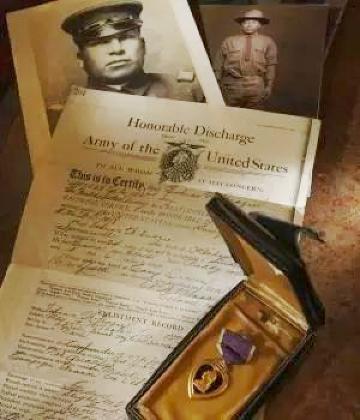

World War I And American

Indians

|

||

|

by Sota Iya Ye Yapi

|

||

|

In 1917 the United States entered into World War I. While Indians were not liable to be drafted, they enlisted in large numbers. Many of the volunteers were eager to count coup, gain war honors, and to maintain the warrior traditions of their tribes. An estimated 10,000 Indians served in the military during the war. The Onondaga Nation, a part of the Iroquois Confederacy, unilaterally declared war on Germany, citing ill-treatment of tribal members who were stranded in Berlin at the beginning of hostilities. The Oneida Nation, another member of the Iroquois Confederacy, also declared war on Germany. The Draft: When the United States entered World War I a draft was implemented. Indian men were required to register for the draft. However, Indians were not generally considered to be citizens at this time, and most Indian men were therefore not citizens. Citizenship for Indians at this time was not determined by place of birth, but by whether or not they had taken an allotment and were considered "competent."

Only those who were citizens could actually be drafted for military duty. Registration for the draft included all Indian males, both those who were citizens and those who were not. The Indian Office (Bureau of Indian Affairs) was instructed to establish draft boards for each reservation. On some reservations, the Indian agents had difficulties in explaining to the men why they needed to register if they could not be drafted. Some Indian leaders, such as Dr. Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai), called for citizenship to be conferred upon Indians before they were drafted. In 1917, Dr. Montezuma wrote in his newsletter Wassaja: "They are not citizens. They have fewer privileges than have foreigners. They are wards of the United States of America without their consent or the chance of protest on their part." In 1918, a number of Gosiute men on the Deep Creek Reservation in Utah and Nevada refused to register for conscription. The Indian agent had attempted to explain to them that the conscription registration was merely a census and that it did not mean that they would actually be drafted, as they were not citizens. Unsatisfied by this explanation, several men refused to register. Consequently, the Indian agent ordered that several men be arrested for inciting draft resistance, and tensions increased. Rumors from both sides of the dispute added to the tension and distrust. The Indians armed themselves and reportedly bought thirty cases of ammunition from the local store. When federal officials tried to arrest two men, the Gosiute refused to surrender them. Army troops were then called in to arrest the supposed ringleaders. They detained about 100 men and arrested six. The six men were eventually freed. In Oklahoma, Ellen Perryman, an unmarried woman from a prominent Creek family, attempted to organize a Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) post to commemorate the deeds of the Loyal Creek during the Civil War. At a meeting at the Hickory Stomp Ground -t he location of the Crazy Snake Rebellion - the meeting became an anti-government rally and a protest against the draft. A mob of "patriotic" citizens then broke up the meeting amidst some sporadic gunfire and verbal threats. This became known at the Creek Draft Rebellion of 1919. Concerned that the publicity from the event would undermine the government's claims for unanimous support for the war, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs ordered an immediate investigation. The subsequent reports claim that Ellen Perryman was disloyal to the government, a possible violation of the Espionage and Sedition Acts. One investigator met with her and concluded that she was demented and recommended that the matter be dropped. The investigation continued and law enforcement agents watched her every move. A warrant was then issued for the arrest of Ellen Perryman. Amidst rumors that the Indians were organizing an uprising, armed agents arrived at the Hickory Stomp Ground to arrest Perryman who was described as being about 40 years-old, heavily built, and about five feet three inches tall. The agents found no uprising, no armed Indians, no draft rebellion, and no Perryman. As the hunt for Ellen Perryman intensified, there were reports that she was in Washington, D.C. with several older Snakes meeting with the German government. At this point the Secret Service and the Bureau of Investigation became involved. For two months Perryman eluded federal agents, but she was finally arrested in Oklahoma and charged with violating the Espionage Act. At her hearing it was agreed to postpone the case indefinitely with the understanding that she would behave herself and keep quiet. This was the end of the Creek Draft Rebellion of 1918. The Rebellion took six months of investigation that included a detachment of the Oklahoma National Guard, dozens of state and local law enforcement officials, the United States Department of Justice, the United States Post Office, the Secret Service, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Military Service:

Even though they could not be drafted, Indian men volunteered to serve. Many saw military service in war time as an opportunity to continue the warrior traditions of their tribes. Many of the warriors counted coup (war honors) and went through tribal war ceremonies both before shipping out and upon returning. One of the problems facing the American forces was communication: since English was frequently spoken by the Germans they could understand radio transmissions as well as telephone conversations (lines were often tapped). American Indians provided an interesting solution. While speaking Indian languages was not encouraged in the United States-in fact it was often punished-many Indian soldiers were fluent in Native languages. One regiment used Choctaw officers to transmit messages in Choctaw regarding troop movements and other sensitive operations. In doing this, the Choctaw had to develop a special Choctaw vocabulary for military words such as machine gun and hand grenade. In 1919, Congress passed an Act which conferred citizenship for all Indians who served in the military or in naval establishments during World War I. Home Front: On the home front, American Indians bought $25 million worth of war bonds which was $75 for every Indian. In 1917, the Round Valley Indians of California wanted to show their support for the War through Red Cross work-making hospital garments, surgical dressings, and Christmas boxes. Their Indian agent, however, excluded them from these activities. Non-Indians in the area did not want to include the Indians in their organization nor did they want to assist them in forming their own chapter. Indian feelings were further inflamed when non-Indians attempted to exclude the Round Valley Indians from a parade to celebrate the end of a Liberty Loan drive to raise funds for the war. The Indian superintendent ignored Indian requests for full participation in the parade and restricted them to a single float. In addition, the superintendent put the Indian service flag at the end of the parade. In response to this discrimination, the Indians called a general meeting of their community and demanded that the agent be present and explain his treatment of them. Approximately 25% of the Round Valley Indian Community attended the meeting, and while the agent drove by the meeting hall several times, he failed to attend. Realizing that no apology was forthcoming, the Indians organized themselves and petitioned Washington to investigate the matter. They also petitioned the Red Cross to grant them a charter as an independent Indian chapter, but the paperwork granted such a chapter was delayed until the end of the war. No investigation of the agent was instigated by the Indian Office. Impact on Reservations: World War I also impacted American Indian reservations. During this time the loss of Indian land increased. During the war-1917 to 1919-the federal government issued more fee patents-that is, moving land from tribal status to individual status-than it had in the previous ten years. During the war, cattle and sugar beet companies convinced the federal government that they were contributing to the war effort. Thus, when they wanted more land, they were able to lease Indian land quickly, cheaply, and easily. In Montana, sugar companies leased 20,000 acres of Crow land without having to consult with tribal leaders and in South Dakota, non-Indian ranchers grazed their cattle on Sioux land without Sioux approval. |

||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2018 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2018 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||