|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 2018 - Volume

16 Number 12

|

||

|

|

||

|

Native American Women

Made History In The Midterms

|

||

|

by Rebecca Nelson -

Newsweek

|

||

|

Here's Why It Took So Long Two years ago, as Americans were locked in a bitter dispute over the presidential election, Deb Haaland stuffed her suitcase full of green chiles and flew from her home state of New Mexico to North Dakota to join a different fight. Thousands of American Indians from tribes across the U.S. had descended on the windswept plains to resist the federal government's incursion into native lands via—naturally—an oil project. The monthslong protest was unprecedented. Authorities maintained that the Dakota Access Pipeline, which would carry approximately 500,000 barrels of crude a day to Illinois, would create thousands of jobs and revitalize the local economy. But Native American communities and environmental activists objected to the pipeline's route, which bisected the ancient tribal lands of the Standing Rock Sioux and tunneled underneath the Missouri River, the tribe's primary water source. The Sioux feared the pipeline would threaten the reservation's water supply should it ever break. Haaland, a citizen of the Laguna Pueblo, a Native American community in New Mexico, and chairwoman of the state Democratic Party, spent four days at the sprawling camp outside the town of Cannon Ball. She called tribal leaders to rally support for the cause. She talked with the people at the camp, who'd traveled across the country to stand up for American Indian rights. One night, she opened her suitcase stash and cooked a big green chile stew over the fire so the protesters could taste a traditional pueblo meal. The protest, she says, touched a nerve for American Indian communities. "It caused a lot of folks to say, 'You know what? People need to listen to Native Americans.'"

Even though President Donald Trump authorized the pipeline's construction in 2017 and it began ferrying oil a few months later, Haaland wasn't finished. The protests gave Native Americans a taste of the power of advocacy. If people heard more American Indian voices, maybe the community wouldn't have to fight for something as vital as clean water. "People went there and saw this coming together of all these tribes in this inspirational atmosphere, and it created a sense of entitlement, that it's our time to do something," says Mark Trahant, the editor of Indian Country Today. Haaland returned to New Mexico determined to keep fighting and, like dozens of native women across the country, decided to run for public office. On Tuesday, she made history, becoming one of the first Native American women elected to Congress, along with Sharice Davids in Kansas (a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation and a Democrat). In an election that produced a number of notable firsts—Muslim congresswomen, the youngest woman ever elected to Congress, the country's first openly gay governor—these victories arguably represent some of the most significant. "It's clear that Americans want representation," Haaland says, the day after her win, of the diverse slate of candidates elected. "I think it could be a turning point for this country."

It's been a long time coming. Though Native Americans are nearly 2 percent of the population, they account for just 0.03 percent of elected officials. The federal government's stained history with indigenous people—genocide, forced assimilation, systemic discrimination—played a decisive role in keeping the community from office. That unrelenting oppression isn't a relic of the distant past; it reverberates across reservations today. In October, the Supreme Court upheld a North Dakota law that requires voters to provide ID that includes a residential address, which Native Americans say unfairly targets them because reservations often don't use street addresses; post office boxes are common. It has led to a profound distrust of the federal government among native people, many of whom have turned inward in an effort to preserve and strengthen what they have left. But the collective power of Standing Rock, along with opposition to Trump and a growing tribal political network, converged to bring more native women into politics than ever before. In total, more than 50 ran for Congress, state legislatures and statewide offices this year—the largest movement of its kind in American history. In her bid for New Mexico's 1st Congressional District, Haaland made her identity a focus of her campaign, heralding herself a "35th-generation New Mexican." Her campaign logo was a rendering of the sun, a yellow orb with bursts of light from four sides, an ancient Zia Pueblo symbol that's also on the state flag. In New Mexico, where 11 percent of the population is native, it resonated. On the stump and on Twitter and in campaign ads, she started using a powerful refrain: "Congress has never heard a voice like mine."

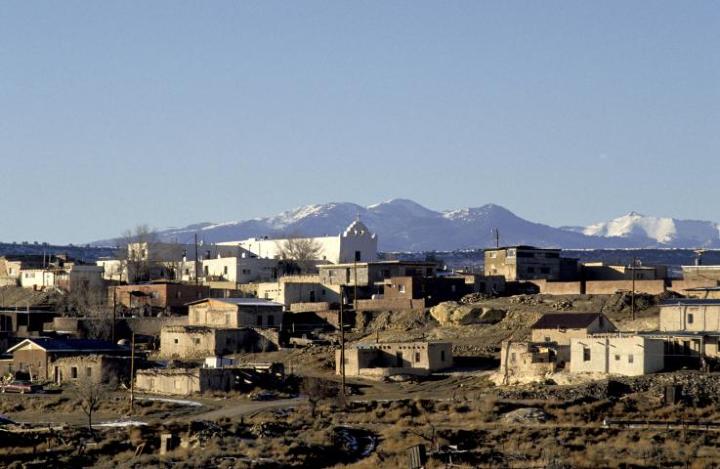

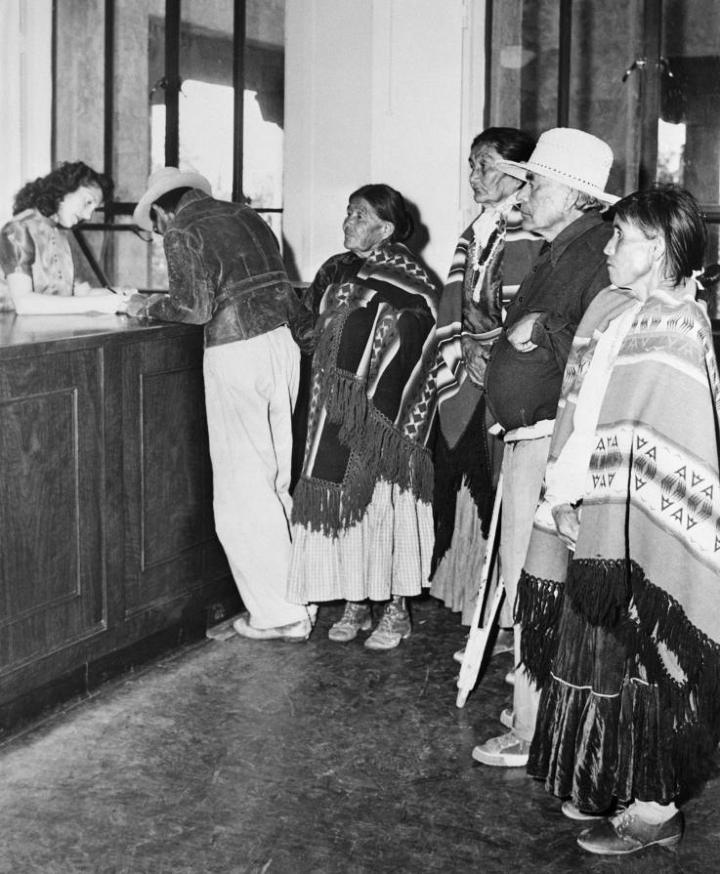

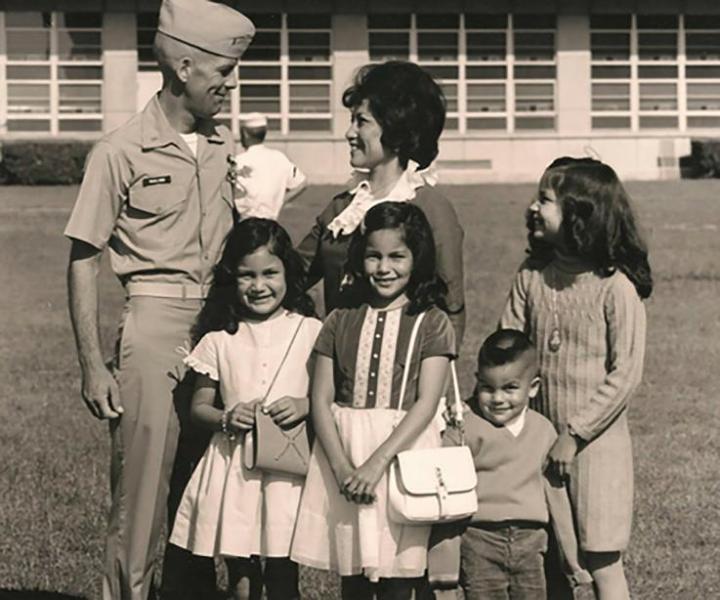

The Laguna Pueblo is a straight shot west from Albuquerque on Interstate 40, which runs parallel to the old Route 66. Once you're out of the city, which happens in a flash, there's virtually nothing on either side of the highway, save great expanses of desert flecked with sagebrush and stubby juniper trees. Flat-topped mesas rise up in the distance. Just 45 minutes away from the city of nearly 600,000, the pueblo feels like another world. While Haaland grew up in a military family and moved around the country as a kid, this is where she spent much of her childhood. There wasn't any running water, and when she was young, she would amble down to the spigot in the middle of the village and fill two buckets to the brim. She'd lug them back the 400 yards to her grandmother's one-room house, so she and her siblings could drink or have a bath. There wasn't electricity either, but they'd build a fire in the brick and clay oven, where her grandmother taught her to bake. Other times, she'd go down to the field with her grandfather and pick worms off ears of corn. Native Americans have lived in this village in rural New Mexico for nearly a thousand years. On a chilly Tuesday evening in August, Haaland, who's 57, takes me on a tour. Her grandmother's house is still here. The spigot is too. "I think that's where I learned to be very conservative with water," she tells me. When you have to haul your own, you conserve. Outsiders are viewed with suspicion here. As we spoke during Newsweek's photoshoot off the side of a two-lane road, three different people driving by stopped to make sure we had the proper permissions to photograph on pueblo land. At one point, a Laguna police officer, alerted by a watchful resident, came to check that our papers were in order. The distrust is understandable. After the genocide of Native Americans at the hands of white settlers, the U.S. government implemented policies designed to erase them. There was Andrew Jackson's 1830 Indian Removal Act, which forced tribes west and away from their land. Then there was the policy of assimilation and 1887's Dawes Act, which aimed to destroy Native American communities by dividing up tribal lands. Thousands of native children were sent to boarding schools so they would learn Anglo-Saxon culture, language and traditions. Many were forced to take "Christian" names. (Haaland's great-grandfather was sent to Carlisle, an infamous American Indian boarding school in Pennsylvania, and her grandmother was sent to a similar program in Santa Fe.) Through the policy of termination, in the 1950s and 1960s, Congress declared that various tribes would no longer receive federal recognition, and thus denied them benefits and other social services. Native Americans weren't granted citizenship until 1924 and were not able to vote in many states for decades after. In New Mexico—which argued that because American Indians living on reservations did not pay property taxes, they were ineligible to vote—they gained the right only after a veteran of World War II sued the state in 1948.

Policies that curtail Native Americans' rights remain. According to the National Congress of American Indians, just 66 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives are registered to vote. Though Latino registration is 57 percent, Native Americans' turnout rate is historically low, consistently 5 to 14 percentage points lower than other racial and ethnic groups. That's partly because of unique obstacles to voting, including the requirement of traditional street addresses. Polling places can be far from rural reservations, with voters sometimes having to travel hours to register or cast a ballot. Native Americans on one Nevada reservation had to travel 270 miles roundtrip to get to the closest polling place in 2016. That year, two tribes there sued the secretary of state under the Voting Rights Act, and a U.S. district judge ordered the establishment of satellite polling places on the reservations. In Utah's San Juan County, Native Americans outnumber white residents. After years of gerrymandering to give white voters disproportionate power, a federal judge redrew the lines in December 2017. But earlier this year, officials kicked a Navajo candidate running for county commissioner off the ballot, alleging that he did not actually live in the state, even though he had voted there for the past 20 years. (Willie Grayeyes's candidacy was reinstated through a court order in August, and he won on Election Day.) "When that's what you're up against, why would you run?" says Natalie Landreth, a senior attorney at the Native American Rights Fund. "The deck has been stacked against Native American candidates forever." Ben Nighthorse Campbell, the first Native American senator, tells me that during his first run for office in Colorado, some of his friends wondered why he'd be interested in joining the government of a country that took everything from his people. "People don't trust the government," says 29-year-old Jade Bahr, a citizen of the Northern Cheyenne tribe who won a race for state representative in Montana. "They don't think that voting is going to do anything." Life in Indian Country is very different from outside of it. "On a reservation, you grow up with a different lifestyle," says Democrat Paulette Jordan, 38, a citizen of the Coeur d'Alene tribe who ran an unsuccessful campaign for governor of Idaho this year. It's a culture focused on listening, on respect for elders, on living harmoniously and, across many tribes, on coming to consensus. Those values aren't easily found in today's political climate. It's a tangible separation too. The more than 500 federally recognized American Indian tribes are sovereign nations, which means Native Americans are, technically, dual citizens. Each sovereignty has a government-to-government relationship with the United States. Preserving and strengthening that status is a central goal for Native Americans, and there's a fear that participating in nontribal elections puts it at risk. Will the federal government revive its termination policies, asked Native American author Jerry Stubben in 2006, if officials see Native Americans as "so assimilated that their own governing structures and institutions are no longer necessary"?

Haaland talks slowly and softly, at times with an almost singsong lilt. She has a square face with deep dimples in both cheeks that linger even when she furrows her brow. Though her long black hair takes forever to blow dry, she doubts she'll ever cut it because of its native symbolism, to dark clouds: "You want to keep your hair long," she tells me, "so that the rain will come." Her mother is Laguna, and her father, who died in 2005, was Norwegian-American. "My mother still raised us in a pueblo household," she tells me. "In spite of the fact that we moved around a lot, we still kept those strong ties to my grandparents and our community of Laguna Pueblo. You can be native wherever you are." We've settled at a café near the University of New Mexico campus. Haaland tells me that politics was not a big part of her early life. Her dad fought in Vietnam for two years, and the family had a small black-and-white TV in the kitchen and would watch for news of the war over dinner, but that was the only mention of current affairs. Her parents, both registered Republicans, supported Ronald Reagan in 1980. Haaland was finally old enough to vote, and she followed her parents. After learning more about Reagan—namely, that he was what she calls a "warmonger"—she switched her party registration to Democrat and vowed to do her own candidate research from then on. After high school, she worked at a bakery in Albuquerque, working the register and decorating cakes. When she was 28, braiding her hair one day before her shift, she had a moment of clarity. "I was like, 'Am I going to be doing this for the rest of my life?'" Neither of her parents went to college, and she didn't know what she needed to do to get there. A family friend at the Bureau of Indian Affairs helped her apply to the University of New Mexico. She got pregnant during her senior year, and by the time she graduated with an English degree, she was nine months along, her cherry-red gown tight against her belly. Four days later, she gave birth to her daughter, Somah. Haaland started a salsa company, Pueblo Salsa, and traveled all around the Southwest to sell her goods at state fairs and fiery food conventions. As a single mom, she brought Somah with her everywhere, blasting Alanis Morissette's Jagged Little Pill from the car stereo. In between road trips, she stayed current on politics. In 2002, when voters on the Lakota Indian reservation turned a tight race for a South Dakota Senate seat—incumbent Democrat Tim Johnson won re-election by just 528 votes—she was blown away. "That really inspired me," she says. "Indians decided between a Democrat and a Republican in this state. And that impressed me deeply." In law school at the University of New Mexico, in 2004, one of her classmates flipped open his laptop to reveal a red-white-and-blue John Kerry bumper sticker. She asked him how she could get involved, and she started volunteering in Kerry's Albuquerque field office. A few years later, her former constitutional law professor was recruiting for a women's candidate training program called Emerge New Mexico and asked her to apply. She had never even thought of running for office. "I just had the inkling to trust her, trust her judgment," Haaland tells me. "If I was left up to my own devices, I may not have thought of it." She graduated from the program in 2007 and soon volunteered full-time for Barack Obama's presidential campaign, taking carloads of people out to the pueblos to canvass. During his re-election campaign, she became Obama's Native American vote director for the state. Haaland ran for lieutenant governor two years later (her mom became a Democrat so she could vote for her in the primary) and, though she lost the general election by 14 points, she became chair of the state Democratic Party in 2015. Throughout, she worked to register Native American voters, going to fairs and parades and rodeos to sign people up. Laguna isn't in her congressional district, but two American Indian communities are, and during her campaign she assigned volunteers to actively court those voters. She didn't set out to put her Native American identity, the historic nature of her candidacy, front and center. But as she started doing more interviews, that's what everyone wanted to talk about. She shrugs. "It's who I am," she says. Why not lean into it? We're eating sopaipillas smothered with honey and New Mexico's ubiquitous green chile, which goes on everything from tacos to cheeseburgers. She takes a bite. "I think people, above all, want to know that they're being represented by somebody who understands what it's like to be them."

There's some debate over who the first Native American man to serve in Congress was, mostly because assimilation efforts meant that many people had some amount of American Indian ancestry. Richard Cain, a South Carolina abolitionist who was first elected to Congress in 1873, was the son of an African-born father and Cherokee Indian mother. Charles Curtis, a congressman and senator from Kansas who eventually became Herbert Hoover's vice president, was half Native American and grew up on the Kaw reservation. There have been a handful of other Native American men to serve in Congress. Today, the only two currently serving are both Republicans from Oklahoma. "A lot of the role I end up playing is educating other members," says Tom Cole, a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation who has represented Oklahoma's 4th Congressional District since 2003. Many of his peers don't understand Native American issues or the federal government's responsibility to tribes. Most of what he deals with, he explains, boils down to tribal sovereignty and a doctrine known as trust responsibility, which stipulates that the property of Native Americans is under the charge of the United States. That responsibility, a fundamental tenet of relations with American Indian tribes, requires the federal government to protect and enhance the property and resources of Native Americans. But because the doctrine is not codified in any single document, "the federal government has to be re-educated every generation on this," Cole tells me. "It's a never-ending battle." Like other minorities, when native voices aren't represented in policymaking, their issues aren't heard, and their communities often suffer. The opioid crisis, for instance, has ravaged the nation as a whole—but it has particularly devastated Native American communities, where overprescribing has filled in for inadequate health care. Between 1999 and 2015, Native Americans and Alaska Natives saw a fivefold increase in overdose deaths, a higher increase than any other group, according to Senate testimony from the chief medical officer at the U.S. Indian Health Service. At least 20 tribes are suing opioid manufacturers and distributors, alleging that the firms aggressively marketed the drugs and shipped large volumes of painkillers to areas near reservations. Nearly 12 percent of Native Americans die of alcohol-related causes, more than three times the percentage for the general population. At some point in Haaland's youth—she doesn't remember exactly when—she started drinking, finally getting sober in her mid-20s. In an ad for her campaign, in between declaring herself a champion for kids and broadcasting her support for affordable health care, she mentioned that she is 30 years sober. "That is something that I want people to know about me," she tells me. "That I know what it's like." This experience is, in part, why she's pledged more resources for recovery services, as well as Medicare for all. Native American women are also more vulnerable to violence. Hundreds have gone missing across the country; at the end of last year, the FBI had 633 open missing person cases for Native American women. A 2016 Department of Justice study showed that 84 percent of American Indian women have experienced violence, and 56 percent have endured sexual violence. Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, a 22-year-old in Fargo, North Dakota, was eight months pregnant when she went missing last August. Her body was eventually found in a nearby river, while her baby was found in the apartment of her killer after it had been cut out of her mother's womb. The story was a major reason why Minnesota state Representative Peggy Flanagan decided to run for lieutenant governor. A Democrat, she won her race on Tuesday. Flanagan, a citizen of the White Earth Nation band of Ojibwe Indians, says LaFontaine-Greywind was well-known in native communities but virtually ignored by most mainstream media outlets. "At best, we are invisible," she says. "At worst, we are disposable." Many of the Native American candidates I talked to spoke of their culture's deep respect for the environment as an influence on their politics. Andria Tupola, a Republican who fell short in her campaign for governor of Hawaii this year, tells me her Native Hawaiian background has made her more environmentally aware. In Hawaiian, "malama 'aina"—to care for the land—is a central value. "The ways that we make policy about our land, or the use of it, can affect generations," Tupola, who's 37, says. In Congress, Haaland says she will champion renewable energy and affordable health care and advocate for American Indian issues. But that advocacy will also include celebrating tribes' successes, like new business openings or thriving schools. According to a June report from the First Nations Development Institute, "the most persistent and toxic negative narrative is the myth that many Native Americans receive government benefits and are getting rich off casinos." Non-natives also associate poverty and alcoholism with American Indian tribes. "We have a lot of good stories to tell too," Haaland tells me. "And I think people should know about them."

To some extent, the record number of Native American women running is a part of the larger women-led resistance to Trump. But the president's harsh treatment of the native population, in his business career and in the White House, provided extra motivation. In a 1993 congressional hearing on American Indian gaming, he said members of a federally recognized Connecticut tribe "don't look like Indians to me." In 2000, he waged an extensive ad campaign against American Indian casinos, accusing Native Americans of rampant drug use and mob ties. He's taunted Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren—who claims, with scant evidence, that she's part Native American—as "Pocahontas," which many Native Americans consider a racial slur. He held an event honoring Navajo code talkers who served in World War II in front of a portrait of Andrew Jackson, whose Indian Removal Act kicked off the Trail of Tears. Trump's administration has sought to limit Native Americans' access to Medicaid. It also shrank Utah's Bears Ears National Monument, which contains sacred Native American sites, so the land could be developed for mining and drilling. Haaland, who ran in a heavily Democratic district, made opposition to the president a touchstone of her campaign, branding herself "Donald Trump's worst nightmare." She tells me that "he needs an Indian 101. I don't think he understands anything about tribes." The infusion of cash from casino gambling has also been a factor in the number of Native Americans running for office. Thanks to the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, tribes have the resources to help fund political pursuits. "Being in politics requires money and funding," says Richard Bernal, the governor of Sandia Pueblo, which is just north of Albuquerque. "The support is there for the tribes now." But it's also the fruits of years of organizing. In 2015, South Dakota state Representative Kevin Killer co-founded Advance Native Political Leadership with Flanagan and two others after being frustrated that Native American voices were being left out of the political conversation. "We need to make sure that we're represented at every single level," Killer, who's 39 and now a state senator, says. "Not only the candidates, but also campaign managers, field organizers, fundraising directors." In September, the group held its inaugural Native Power-Building Summit, in Albuquerque, which featured workshops and trainings ranging from how to finance a campaign to how to get a political message out. "It's been slowly building," Killer tells me. South Dakota didn't repeal its state law denying American Indians the right to vote until 1951, and even after that, other legal restrictions kept them from voting in some county elections until as late as 1980. That was Killer's grandparents' generation. "Then our parents have the wherewithal to actually say, 'OK, maybe we should vote, or maybe we should talk about politics.' So they start voting, and then they impart it to us." His generation is taking the next step: running for office. Last year, in New Mexico, Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver started a Native American Voting Task Force to increase voter registration and turnout among American Indian communities. The group, which does not have any state funding, has put on informal voter registration drives in pueblos and American Indian communities across the state, and this year issued the state's first Native American voting guide, which includes information on native language interpreters at polling places. In August, 69,000 Native Americans were registered to vote in the state, according to a spokesman for the secretary of state. (It's hard to know what percentage that represents because the state doesn't have firm data on the eligible voting population of the community.) Such advances have, like many 2018 campaigns with a minority candidate, been met with racial challenges. Because Haaland's father was white, she's had people questioning her decision to put her Native American identity at the forefront of her campaign. In September, her opponent, Republican Janice Arnold-Jones, drew criticism for casting doubt on Haaland's history-making potential. "There's no doubt that her lineage is Laguna, but she is a military brat, just like I am," Arnold-Jones said in an interview with Fox News. "I think it evokes images that she was raised on a reservation." And recently, on her campaign Facebook page, someone asked why she's denying her Norwegian heritage. "I'm like, 'I'm not denying it.' My last name is Haaland, for God's sake," she says. "That's Norwegian." "I am who I am," Haaland adds. "I choose to identify as Native American. That's who I am. That's the culture I'm closest to because my mom and my grandmother taught me so much." On a hazy Wednesday evening in August, I drive to the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque, where Haaland is hosting a fundraiser with tribal leaders from various pueblos. As I make my way around the room, the most common refrain I hear is some variation of: After years of being left out of the conversation, we're finally being seen. When I ask Ricardo Campos, a 65-year-old Native American who lives in Albuquerque, what Haaland's candidacy means to him, he clasps his hands together and looks at me. "It's a long time coming," he tells me, tears running down his face. Kevin Beltran, a 25-year-old citizen of the Zuni Pueblo, says that her ascent to Congress gives Native Americans "an opportunity to be heard." Ray Loretto, the former governor of Jemez Pueblo, tells me, "We haven't been quite on the map. I hope our voice can be carried all the way to Washington." Lynn Toledo, a cousin of Haaland's, works for the Jemez Pueblo. We chat for a few minutes casually, and she tells me Haaland can help Native Americans because she understands what life is like for them. Suddenly, she bursts into tears. "It really did hit me," she says, her voice dropping to a whisper. "We're not forgotten. We're still here." As she weeps, the rain starts to pour feverishly outside, pooling on the balcony and obscuring the view of the Sandia Mountains. Lightning flashes in the distance. She turns away from the people milling around the room and toward the floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the city. "The Earth is crying too." |

||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2018 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2018 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||