|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

March 2017 - Volume

15 Number 3

|

||

|

|

||

|

9,000-Year-Old Kennewick

Man Set To Receive Native American Burial After Decades In Limbo

|

||

|

by Ben Guarino - Washington

Post

|

||

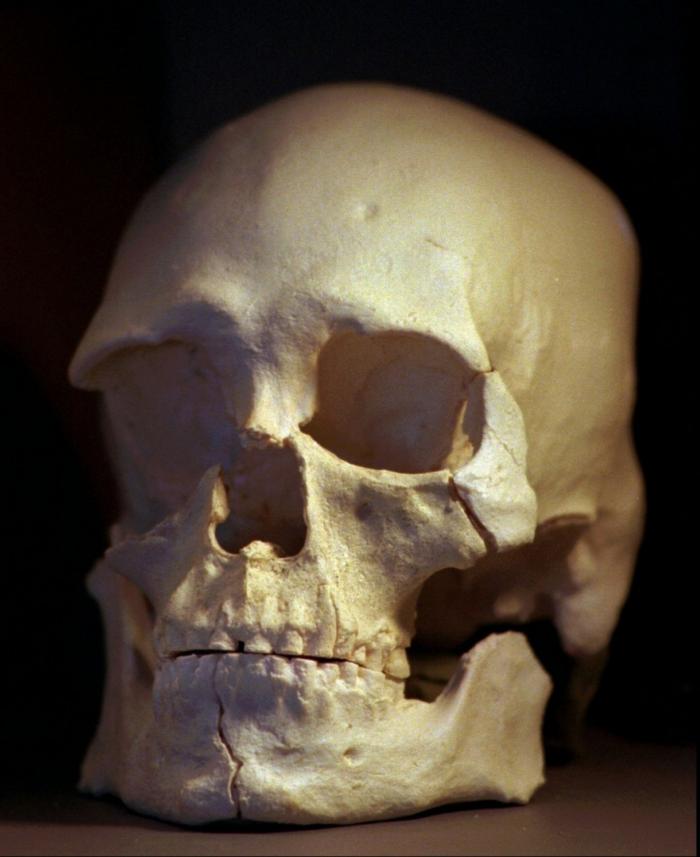

Beer in hand, 21-year-old Will Thomas bent down in the middle of the Columbia River to grab what he thought was a rock. "Look, Dave," he reportedly told his friend Dave Deacy. It was 1996, and the college students were trying to sneak into a boat race near Kennewick, a small city in the southeast corner of Washington. Their master plan, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer, was to check out girls. "I found a head," he joked. It wasn't until after he lifted the skull out of the water that Thomas realized his jest wasn't factually incorrect. The duo tucked the cranium on dry land and moseyed over to the race. Afterward, they flagged a police officer, handing off the head in the bottom of a 5-gallon bucket. The skull and a few other bones then passed from the sheriff's office to the coroner to a local forensic anthropologist, James Chatters, until someone carbon dated a finger and realized the remains were about 9,000 years old — making them among the oldest remains in North America. The Kennewick Man, nine millennia after his death, was born. Thomas and Deacy believed they had found a victim of murder or suicide. They had, in fact, found a victim — but the assault occurred long before Egyptians got around to building the pyramids. Chatters scoured the site on the Columbia River, finding an almost complete skeleton in freshly-eroded mud. While he was alive, the Kennewick Man had had a rough existence: One arm was withered, as though crushed, and he had been stabbed in the hip with a rock spear with the serrated tip embedding itself in his pelvic bone. It's believed he survived the initial attack but not the infection. Once the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which had control over the Columbia River property, caught wind of the bones' ancient age, the agency demanded the remains. A local tribe, the Umatilla, had claimed the Kennewick Man as an ancestor; the Native American group wanted to lay the skeleton to rest according to custom. Chatters, who had teamed up with paleoanthropologists like the Smithsonian Institute's renowned bone expert Douglas Owsley, resisted.

In the other corner was a coalition of five Native American groups — the Nez Perce, Yakama, Wanapum and Colville tribes, along with the Umatilla, who refer to the Kennewick Man as the Ancient One. Their legal footing, they say, is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act — legislation enacted in 1990 as a way to return cultural items kept by federal agencies and museum collections. By September of 1996, the Army Corps of Engineers had possession of the remains — minus a few thigh bones, which mysteriously vanished in the process. (Years later, the Federal Bureau of Investigation would hunt for the bones and launch an investigation when the body parts resurfaced in the Kennewick sheriff's evidence vault.) In response, Owsley and seven other scientists, wanting to examine the bones, sued the Corps in federal court. "We believe that something this ancient is a precious gift," Alan Schneider, an attorney for the paleontologists, told Newsday at the time. "If we repatriate it we should gather as much information as possible for future generations." Meanwhile, the Kennewick Man surfaced from the mud only to be sealed in a safe at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, beyond the reach of camera lenses and analytical equipment. Umatilla religious leader Armand Minthorn was unimpressed with the researchers' entreaty. "Some scientists say that if this individual is not studied further, we, as Indians, will be destroying evidence of our own history," he said in a statement on behalf of his tribe as the debate raged on. "We already know our history. It is passed on to us through our elders and through our religious practices."

But a sliver of hope remained for the five tribes. According to the Seattle Times, the appeals court wrote that if data surfaces indicating the Kennewick Man "may be Native American, it might cause us to reopen the analysis." In the meantime, Owsley had the liberty to move forward with his research. As the Smithsonian Magazine reported: A vast amount of data was collected in the 16 days Owsley and colleagues spent with the bones. Twenty-two scientists scrutinized the almost 300 bones and fragments. Led by Kari Bruwelheide, a forensic anthropologist at the Smithsonian, they first reassembled the fragile skeleton so they could see it as a whole. They built a shallow box, added a layer of fine sand, and covered that with black velvet; then Bruwelheide laid out the skeleton, bone by bone, shaping the sand underneath to cradle each piece. Now the researchers could address such questions as Kennewick Man's age, height, weight, body build, general health and fitness, and injuries. They could also tell whether he was deliberately buried, and if so, the position of his body in the grave. Next the skeleton was taken apart, and certain key bones studied intensively. The limb bones and ribs were CT-scanned at the University of Washington Medical Center. These scans used far more radiation than would be safe for living tissue, and as a result they produced detailed, three-dimensional images that allowed the bones to be digitally sliced up any which way. With additional CT scans, the team members built resin models of the skull and other important bones. They made a replica from a scan of the spearpoint in the hip. As work progressed, a portrait of Kennewick Man emerged. He does not belong to any living human population. But Owsley and the Smithsonian team weren't the only scientists who wanted in on the Kennewick Man's dance card. An international team of geneticists, led by researchers at Stanford University and the University of Copenhagen, extracted biologic information from 200 milligrams of Kennewick Man hand bone. And the results that they published, in the journal Nature in 2015, flew in the face of Owsley's morphologic work. "Using ancient DNA, we were able to show that Kennewick Man is more closely related to Native Americans than any other population," said Morten Rasmussen, a Stanford geneticist and author of the research, in a statement. This was just the sort of evidence that could fly through the window the appeals court had left open. A year after the Nature announcement, a team at the University of Chicago confirmed that the Kennewick Man is genetically related to Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest. And, on Wednesday, the Army Corps of Engineers — which is in possession of the remains — declared that it's working with the Native American tribes to coordinate a burial. The tribes responded positively to the news of the Kennewick Man's return. But a representative for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla told the Associated Press that the scientific evidence "acknowledges what we already knew and have been saying" for the past 20 years. As the Umatilla leader Minthorn said in 1996: "If this individual is truly over 9,000 years old, that only substantiates our belief that he is Native American. From our oral histories, we know that our people have been part of this land since the beginning of time." |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2017 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2017 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||