|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

March 2017 - Volume

15 Number 3

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Origin of

Counting Coup Honor Began With Birds |

||

|

by Dakota Wind - The

First Scout

|

||

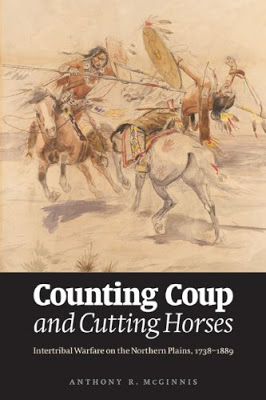

Great Plains, N.A. (TFS) – The traditional war honor of counting coup reaches back to a time before the First Nations walked upon Makoce Waste (Beautiful Country; North America). When the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires; the Great Sioux Nation, or "Sioux") arrived, they learned to survive by first observing nature. When the Oceti Sakowin learned warfare, they were prepared for the First Battle by Thokeya (the very First man), aided by Inktomi (the Spider Nation in this instance, not the legendary trickster) and Zitkala (the Bird Nation). With a heavy heart, Thokeya gave the first bow and arrows to men. "Misunkala (Little Brother/s)," said Thokeya, "the time to give you weapons is now and I am sorry to do so. Now, at last there is war in the hearts of animals and man." According to Ohíyesa (The Winner; aka Dr. Charles Eastman) and his work Wigwam Evenings, Thokeya gave them a spear as well and showed them how to use these tools.

Inktomi fashioned stone tools for arrows, spears, and knives, then scattered these things across Makoce Waste for the people to find and use. They say that Inktomi continued to knap stone up until recent times. The high-pitched ring of stone on stone was heard by Lakota men and women on Standing Rock. "Some people have heard him at work, but could never see him. I have, myself, heard him at work, chipping stones. It was a small hole south of Fort Yates where I heard him working. He went slow (chip chip). We got within a few feet of the hole, when he would stop and we could not find him then. When we went away he worked again," said Bull Bear to Col. A. Welch in 1926. In the First Battle, the Zitkala had chosen the side of the animals. In another story, there was a Great Race around Hesapa (the Black Hills) between man and animal, to decide who would hunt who. Zitkala stood with man, because like man, Zitkala has two legs.

The Oceti Sakowin observed how Zitkala defended their nests from one another and from other threats. In 1919, Sinte Wakinyan (Thunder Tail; Oglala) shared that all Zitkala are alike in the regard they have for their young. When approached, Zitkala cries out vigorously, and if the interloper still advances, only then do they fly out and give chase. "...iwichacupi chinpi sni he un hechapi (...they do not want their children taken, that's why they do this)," said Sinte Wakinyan. Sinte Wakinyan continued: "Woeye kin le othehike Iapi: 'Blihic iyapo! Zitkala wan iye wiphe yuha sni yes chinca awichakiksiza,' eyapica na he tona okichize el ophapi kin hena lila ota waontonyanpi ktA ogan skanpi nakun tapi eyas na oyate kin he un awaniglakapi (They have a determined saying: 'Take courage! Birds have no weapons and yet they keep their young,' they said. They fight determinedly and wound their many enemies, sometimes killing them to protect what is theirs)." "Hehanl ichinunpa woeye kin: 'Zitkala owe oyasin kinyanpi na okta sicapi.' he un oyate kin okichize el Zitkala iyechel skanpi (They have a second saying: 'All the birds fly and strike the bad ones.' In battle, the people are like birds)." Counting coup then, can be taken by way of touching the enemy with one's own hand, with a stick, quirt, lance, bow, staff, or even a rifle. The Oceti Sakowin call this honor: Thoka kte ("Strike/Kill an enemy"). The coup stick is called chanwapaha. Recounting these deeds is called WaktoglakA. The victory dance is a Waktegli Wachipi.

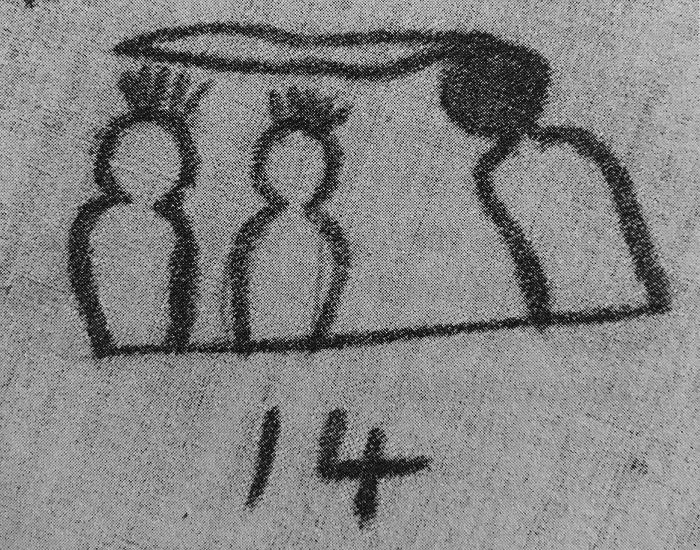

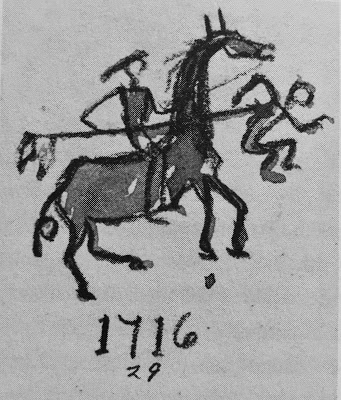

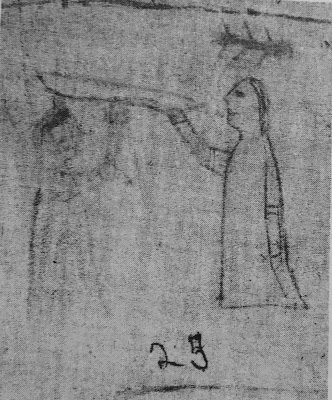

The Baptiste Good Winter Count (Sichangu; aka Brule) recalls a curious development in warfare. In the entry for 1714-1715 a warrior astride a horse, carrying a pine lance, came to attack, but killed nothing. According to Dr. Corbusier's notes, this mounted attack was the first of its kind experienced by the Sichangu. The rider certainly didn't come to joust. He came to collect war honor, not to kill. The Rosebud Winter Count (Sichangu) mentions coup a few times, the earliest of which will be shared here. In 1774-1775, a man named Red Dragonfly counted coup using a bow on a Crow Indian. A winter count entry was selected because it was outstanding. Counting coup was bold and daring, and young men were expected to be so as well. Not every war party went to count coup. In fact, some had coup counted on them, and the unlucky returned in humiliation. There was something exceptional about this particular deed that needed to be remembered. The Long Soldier Winter Count (Hunkpapha) mentions coup in the entry for 1816-1817, "2 Sioux killed 2 Crows and scalped them and blackened their own faces for gladness and came home [sic]." For the Hunkpapha, there are four coups: first coup is for the one who struck the enemy first, alive or dead, second coup is for the one who struck second, third coup for third strike, and fourth coup for fourth strike. A coup must be substantiated by an eyewitness. According to Mahto Wathakpe (John Grass), first coup is designated by an eagle tail feather with the quill painted red, bound in red cloth, or embroidered with quillwork. A first coup feather may be colored or notched to include second, third, or fourth coup. A rider would designate first coup with a horse tail affixed beneath the horse's bridle bit. Other methods of showing one's first coup included attached a streamer of horsehair to the tip of an eagle feather, or a small tuft of plumage was carefully glued to the tip of the feather.

Conflict wasn't about taking life, but securing personal honor and demonstrating courage. Warfare, according to Ohíyesa, "... was held to develop the quality of manliness and its motive was chivalric or patriotic, but never the desire for territorial aggrandizement or the overthrow of a brother nation." Lakota military strategy was carefully planned to avoid unnecessary risks. In 1879, a young Lt. William Philo Clark was stationed in Dakota Territory. There he was charged with learning the Plains Indian sign language. Clark recorded the sign for counting coup as: hold the left hand, back to left and outwards, in front of the body, index finger extended and pointing to front and right, others [remaining fingers] and thumb closed; bring right hand, back to front, just in rear of left [hand] and lower, index finger extended, pointed downwards and to the left, right index finger under left, other fingers and thumb closed; raise right hand, and turn it by wrist action so that end of right index strikes sharply against [the] side of the left as it passes. The Oceti Sakowin learned to survive by observing nature. Especially Zitkala (the bird nation). Zitkala built nests at certain times of the year, and defended their young and their Makoce (country; territory) when needed. Zitkala even help each other sometimes; the meadowlark never reminds the prairie chicken of the time they defended their ground nests from a common foe. Zitkala doesn't disparage the ways of other Zitkala. When the seasons change, each respects its time and calling.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Eastman, Charles A., Dr., and Elaine Goodale Eastman. Wigwam Evenings: 27 Sioux Folktales. Dover ed. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 2000. Welch, A. B., Col. "Life on The Plains in The 1800's." Welch Dakota Papers. November 2, 2011. Accessed January 5, 2017. http://www.welchdakotapapers.com/. Stars, Ivan, Peter Irin Shell, and Eugene Buechel. Lakota Tales And Texts. Edited by Paul Manhart. Pine Ridge, SD: Red Cloud Lakota Language and Cultural Center, 1978. Lakota Winter Counts Online. March 3, 2005. Accessed January

12, 2017. Flying By, Wilbur. Interview by Charles I. Walker. Lakota Traditions. Wakpala, SD, 2001. The Year The Stars Fell: Lakota Winter Counts At The Smithsonian. Edited by Candace S. Greene and Russell Thornton. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. Clark, W. P. The Indian Sign Language. First ed. Lincoln: U of Nebraska, 1982. Mails, Thomas E. The Mystic Warriors of the Plains. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1972. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2017 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2017 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||