|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

March 2017 - Volume

15 Number 3

|

||

|

|

||

|

Cahokia, America's

Great City

|

||

|

by Alice B. Kehoe- Indian

Country Media Network

|

||

|

What happened to Cahokia inhabitants?

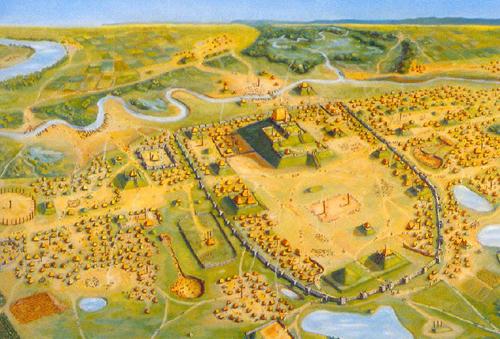

Larger than London or Paris in its time, what is now America’s heartland had a magnificent city between 1030 and 1200 CE. Now known as Cahokia, the city occupied the wide floodplain where the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers meet, near present-day St. Louis. Like traditional capital cities around the world, Cahokia displayed monumental architecture, making it an awesome theater of power. In its center was (and still is) a mound larger than the Egyptians’ pyramids at Giza, a mound nearly as huge as the Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan or the Great Pyramid of Cholula, in Mexico. Its flat top towering 100 feet high covers more than a football field, its base measures 1,000 feet by 700 feet. In front stretches the Grand Plaza, which measures 1,000 feet by 1,300 feet, and is made perfectly flat by filling in gullies and layering special soil over the whole. At the far end and along the sides rise more mounds, 70 feet high. All were capped with colored clays––blue, white, or black.

Beyond the magnificent center were more plazas encircled by mounds, and beyond the city center were thousands of homes and farmsteads, as far as the eye could see on both sides of the river. Villages dotted the uplands, some with their own ritual mounds. At four points where river narrows with bluffs allowed soldiers to guard entry to the floodplain, carved thunderbirds with cross-in-circle territory signs mark in stone the state’s defended boundaries. Hidden in plain sight for centuries, today a UNESCO World Heritage site, Cahokia never was acknowledged in post-contact histories of America. Cahokia was the only true city north of Mexico before the establishment of the United States. In its plan of plazas surrounded by elevated buildings, and in its intensively farmed cornfields, Cahokia resembles the cities of Mexican empires; it follows their ideal city, “Tollan,” in design and in location alongside a marsh rich in foodstuffs. The dates of Cahokia’s rapid building and sudden collapse coincide with the dates for what the Aztecs called the Toltec empire, preceding the Aztecs’ movement into central Mexico. Although the Aztecs told the Spaniards that the Toltec capital was at Tula, northwest of the Aztecs’ Tenochtitlan (Mexico City), it may have been at Cholula to the southeast, the Aztecs’ bitter enemies. Cholula’s own histories say the city was ruled by the Toltecas, that in about the ninth century CE it was conquered by armies from the Gulf Coast region, then re-conquered in 1200 by Toltecas allied with Chichimec bowmen recruited from northwest Mexico. During the period of Gulf Coast invaders’ rule, Cholula hosted the greatest international markets of Mexico and the principal temple to Quetzalcoatl, drawing hundreds of thousands of pilgrims. Its market was especially famous for beautiful feather headdresses and cloaks. Cahokia’s rapid building—and its collapse—coincide with this Toltec empire’s dates. So do the dates for Chaco, the largest town in the American Southwest. Archaeological evidence proves that Chaco traded turquoise thousands of miles into central Mexico during the Toltec period, and imported live parrots, for their brilliant feathers, all the way from southeast Mexico. Cahokia has no parrot bones or eggshells (at least none discovered, in this vast site); its only surviving evidence of contact with Mexico, other than the city plan with mounds around rectangular plazas, is human teeth filed to points in a fashion very popular in Toltec Mexico. Except for one filed tooth from Chaco, the 18 known filed teeth from Cahokia burials are the only filed teeth known north of Mexico.

Here we have Cahokia at the hub of transportation in continental North America, where St. Louis is, the Mississippi flowing from its docks to the Gulf of Mexico. We know, from De Soto’s chroniclers and other early explorers, that the nations along the Mississippi had impressively large canoes, as well as slaves. Did Cahokia’s rulers or traders ride the river to Mexico, then take their slaves to Cholula to sell, to be blessed by the Feathered Serpent’s priests, and to buy unbelievably luxurious feather regalia at the market? Perhaps be fashionably beautified by getting their front teeth filed to sharp points? Besides their slaves, they could have brought and sold finely tanned deerskins––commodities produced and sold in quantities in North American native markets at the time of the first European colonists and pulled into transatlantic trade by those colonists. Neither slaves nor deerskins would leave archaeological evidence that they were commodities. If Cahokia and Chaco had organized trade with Toltec Mexico, a clue is the match between their and the Toltec empire’s beginning and end dates. Wealth from dealing with the aggressively market-oriented Toltecs, likely actually the Gulf Coast conquerors of Cholula, and adopting Mexicans’ corn and agricultural methods, can explain the rapid building of the two anomalous North American cities, and collapse of the Toltec trading empire at 1200 explains the collapse of Cahokia, already beset by enemies fighting against Cahokia’s slave raids. What happened to the Cahokians? Today’s Osage Nation believes that their forebears, including those of the related Ponca, Omaha, Kansa, and Quapaw, were rulers of Cahokia. When their Mexican markets collapsed and their enemies attacked, the Osage retreated up the Missouri to a rich and defensible plateau, their historic homeland. Today, the Osage Nation is beginning to buy back some of its forebears’ mounds at the outskirts of Cahokia. Alice Beck Kehoe is Professor of Anthropology, emeritus, at Marquette University, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. |

||||||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2017 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2017 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||