|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

April 2016 - Volume

14 Number 4

|

||

|

|

||

|

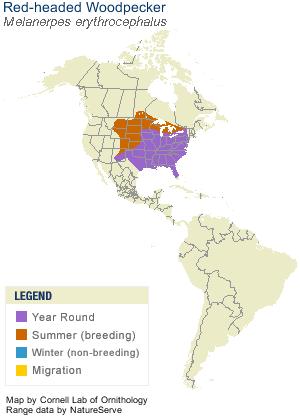

Red-headed Woodpecker

(Melanerpes erythrocephalus) |

||

|

by Cornell Lab of Ornithology

|

||

|

Find This Bird Backyard Tips

Cool Facts

Red-headed Woodpeckers breed in deciduous woodlands with oak or beech, groves of dead or dying trees, river bottoms, burned areas, recent clearings, beaver swamps, orchards, parks, farmland, grasslands with scattered trees, forest edges, and roadsides. During the start of the breeding season they move from forest interiors to forest edges or disturbed areas. Wherever they breed, dead (or partially dead) trees for nest cavities are an important part of their habitat. In the northern part of their winter range, they live in mature stands of forest, especially oak, oak-hickory, maple, ash, and beech. In the southern part, they live in pine and pine-oak. They are somewhat nomadic; in a given location they can be common one year and absent the next.

Red-headed Woodpeckers eat insects, fruits, and seeds. Overall, they eat about one-third animal material (mostly insects) and two-thirds plant material. Their insect diet includes beetles, cicadas, midges, honeybees, and grasshoppers. They are one of the most skillful flycatchers among the North American woodpeckers (their closest competition is the Lewis’s Woodpecker). They typically catch aerial insects by spotting them from a perch on a tree limb or fencepost and then flying out to grab them. Red-headed Woodpeckers eat seeds, nuts, corn, berries and other fruits; they sometimes raid bird nests to eat eggs and nestlings; they also eat mice and occasionally adult birds. They forage on the ground and up to 30 feet above the forest floor in summer, whereas in the colder months they forage higher in the trees. In winter Red-headed Woodpeckers catch insects on warm days, but they mostly eat nuts such as acorns, beech nuts, and pecans. Red-headed Woodpeckers cache food by wedging it into crevices in trees or under shingles on houses. They store live grasshoppers, beech nuts, acorns, cherries, and corn, often shifting each item from place to place before retrieving and eating it during the colder months. Nesting

Nest Description Both partners help build the nest, though the male does most of the excavation. He often starts with a crack in the wood, digging out a gourd-shaped cavity usually in 12–17 days. The cavity is about 3–6 inches across and 8–16 inches deep. The entrance hole is about 2 inches in diameter.

The male selects a site for a nest hole; the female may tap around it, possibly to signal her approval. They nest in dead trees or dead parts of live trees—including pines, maples, birches, cottonwoods, and oaks—in fields or open forests with little vegetation on the ground. They often use snags that have lost most of their bark, creating a smooth surface that may deter snakes. Red-headed Woodpeckers may also excavate holes in utility poles, live branches, or buildings. They occasionally use natural cavities. Unlike many woodpeckers, Red-headed Woodpeckers often reuse a nest cavity several years in a row.

Red-headed Woodpeckers climb up tree trunks and main limbs like other woodpeckers, often staying still for long periods. They are strong fliers with fairly level flight compared to most woodpeckers. They often catch insects on the wing. Prospective mates play “hide and seek” with each other around dead stumps and telephone poles, and once mated they may stay together for several years. Both males and females perform aggressive bobbing displays by pointing their heads forward, drooping their wings, and holding their tails up at an angle. They are territorial during the breeding season and often aggressive and solitary during the winter. Red-headed Woodpeckers are quick to pick fights with many other bird species, including the pushy European Starling and the much bigger Pileated Woodpecker. Their predators include snakes, foxes, raccoons, flying squirrels, Cooper’s Hawks, Peregrine Falcons, and Eastern Screech-Owls. Migration

Red-headed Woodpeckers declined by over 2% per year from 1966 to 2014, resulting in a cumulative decline of 70%, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey. Partners in Flight estimates a global breeding population of 1.2 million, with 99% spending part of the year in the U.S., and 1% in Canada. The species rates a 13 out of 20 on the Continental Concern Score. Red-headed Woodpecker is on the 2014 State of the Birds Watch List, which lists bird species that are at risk of becoming threatened or endangered without conservation action. The species is also listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List. These woodpeckers were common to abundant in the nineteenth century, probably because the continent had more mature forests with nut crops and dead trees. They were so common that orchard owners and farmers used to pay a bounty for them, and in 1840 Audubon reported that 100 were shot from a single cherry tree in one day. In the early 1900s, Red-headed Woodpeckers followed crops of beech nuts in northern beech forests that are much less extensive today. At the same time, the great chestnut blight killed virtually all American chestnut trees and removed another abundant food source. Red-headed Woodpeckers may now be more attuned to acorn abundance than to beech nuts. Though the species was common in towns and cities a century ago, it began declining in urban areas as people started felling dead trees and trimming branches. After the loss of nut-producing trees, perhaps the biggest factor limiting Red-headed Woodpeckers is the availability of dead trees in their open-forest habitats. Management programs that create and maintain snags and dead branches may help Red-headed Woodpeckers. Although they readily excavate nests in utility poles, a study found that eggs did not hatch and young did not fledge when the birds nested in newer poles (3–4 years old), possibly because of the creosote used to preserve them. In the middle twentieth century Red-headed Woodpeckers were quite commonly hit by cars as the birds foraged for aerial insects along roadsides. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2016 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2016 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

The

gorgeous Red-headed Woodpecker is so boldly patterned it’s

been called a “flying checkerboard,” with an entirely

crimson head, a snow-white body, and half white, half inky black

wings. These birds don’t act quite like most other woodpeckers:

they’re adept at catching insects in the air, and they eat

lots of acorns and beech nuts, often hiding away extra food in tree

crevices for later. This magnificent species has declined severely

in the past half-century because of habitat loss and changes to

its food supply.

The

gorgeous Red-headed Woodpecker is so boldly patterned it’s

been called a “flying checkerboard,” with an entirely

crimson head, a snow-white body, and half white, half inky black

wings. These birds don’t act quite like most other woodpeckers:

they’re adept at catching insects in the air, and they eat

lots of acorns and beech nuts, often hiding away extra food in tree

crevices for later. This magnificent species has declined severely

in the past half-century because of habitat loss and changes to

its food supply.