|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

April 2016 - Volume

14 Number 4

|

||

|

|

||

|

EBCI Ancestors Remained

East For Various Reasons

|

||

|

by Will Chavez- Interim

Executive Editor Cherokee Phoenix

|

||

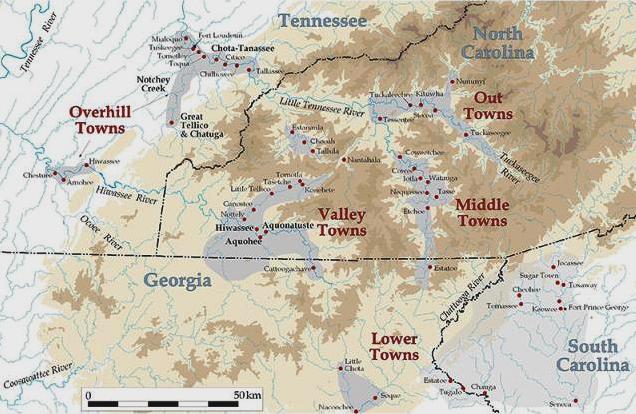

CAPE GIRARDEAU, Mo. – The common perception of why the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians' ancestors remained in North Carolina after the Trail of Tears in the 1830s is that many of them hid in western North Carolina's mountains. During a presentation at the Trail of Tears Association Conference at Cape Girardeau, historian and genealogist Anita Finger Smith of Cherokee, North Carolina, covered the five circumstances during the early 19th century that contributed to the EBCI's ancestors remaining east. "Hopefully, it will clear up some of the misconceptions as to why the EBCI remained after the removal of Cherokee to lands west of the Mississippi," she said. Finger Smith said during the "Contact Period" from 1670-1710, which was prior to extended contact with Europeans, North Carolina Cherokees' settlement patterns varied with individual farmsteads, small villages and clustered towns. Towns were defined by the presence of a townhouse or public building, which was the focal point of civil, political and religious activity. Summer and winter homes ringed a central plaza used for ceremonies, dances and games. During the "Colonial Period," ranging from 1710-85, town clusters

within the Cherokee Nation were described mainly by river drainage

systems. These included the "Lower Towns" along the upper Savannah

River and its tributaries. The "Overhill Towns" were along the upper

Tennessee and lower Little Tennessee rivers. North Carolina Cherokee

settlements were designated the "Out, Middle and Valley Towns."

The "Valley Towns" were along the upper Hiwassee, Nantahala and Valley rivers. The "Middle Towns" were situated along the upper Little Tennessee River drainage basin, while the "Out Towns" were located along the Oconaluftee and Tuckaseegee Rivers. The "Out Towns" formed the location of the current Qualla Boundary, commonly referred to as the Cherokee Indian Reservation. The "Federal Period," from 1785 to 1820 was an era of change for much of the CN throughout the southeast. The first two decades of the 19th century witnessed attempts by the Americans to "civilize" the Cherokees. Mixed bloods in the "Overhill" and "Lower" settlements led an economic and social change while the "Valley, Middle and Out Towns" of North Carolina were less affected by contact with and pressure from the Anglo-Americans. "This was based largely on their geographic isolation. This region contained a larger proportion of full-bloods, less wealth and less exposure to Christianity than most of the Cherokee Nation," Finger Smith said. However, as the new United States expanded westward, the settlement pattern, as the North Carolina Cherokees knew it, was about to change. In 1819 the U.S. Congress ratified a treaty, supplementing a treaty of two years earlier, that ceded a large portion of the CN, including the majority of land in North Carolina, to the federal government. The region around the "Middle and Out Towns" was included. The 1809 Meigs census of the CN totaled 12,395 while only 1,065 Cherokees were enumerated in the "Middle and Out Towns." This indicated that there were 1,065 North Carolina Cherokees whose land would now be excluded from the CN because of the 1819 treaty. The treaty states: "The United States agrees to pay, according to the treaty of July 8, 1817, for all valuable improvements on land within the country ceded by the Cherokees, and to allow a reservation of 640 acres [one square mile] to each head of a family who elects to become a citizen of the United States…" Finger Smith said 91 "Middle and Out Town" heads of Cherokee households filed claims for the 640-acre reservations. They agreed to renounce their CN citizenship, and become known as the "Citizen Cherokee." In August 1824, North Carolina negotiated with the "Citizen

Cherokee" a contract for payment of their 640-acre reservations

and allowed them to settle elsewhere in the area. Some of the "Citizen

Cherokee" moved to the "Valley and Out Towns," which were still

within the CN, but most of the "Citizen Cherokee" settled near a

site later called Quallatown, becoming known as the Oconalufteee

or Lufty or Qualla Indians. During the "Nationalist Period" from 1820-35, the Quallatown Indians lived among their few white neighbors, abiding North Carolina's laws. In 1830, a year after taking office, President Andrew Jackson pushed through Congress legislation called the "Indian Removal Act." It allowed the president to negotiate removal treaties with tribes living east of the Mississippi River. Under these treaties, the Indians were to give up lands east of the river in exchange for lands to the west. A prelude to removal was the 1835 Cherokee Census. It states that 3,644 Cherokees lived in North Carolina, including those in Quallatown. The onset of the Removal Period occurred with the Treaty of New Echota on Dec. 29, 1835, by some Cherokee leaders. Article 12 of this treaty contained a loophole that read: "Those individuals and families of the Cherokee Nation that are adverse to a removal to the Cherokee country west of the Mississippi and are desirous to become citizens of the States where they reside and such as are qualified to take care of themselves…" "This meant any Cherokee choosing to remain would have to acquire their own land and otherwise fend for themselves. This loophole would soon aid the Quallatown Cherokee in their opposition to the removal," Finger Smith said. In January 1836, a white attorney named William Thomas agreed to represent the Indians of Quallatown, Cheoah (Buffalo Town) and several smaller settlements. He was to inform federal authorities that the "Citizen Cherokee" living in Quallatown intended to stay in North Carolina, and he was to obtain their share of the treaty benefits. Because of the Quallatown Indians' unusual citizenship status, Thomas won recognition of their right from the U.S. government and the treaty party of the CN. This ensured that the Quallatown Cherokees were not legally subject to the forced removal. In September 1837, 60 Quallatown heads of families, representing 333 Cherokees, were granted preliminary approval to remain. Thomas was without doubt the most important individual connected with the EBCI's history for 40 years or more. His stance on behalf of the "Citizen Cherokee" was the first circumstance contributing to the EBCI's genesis. The second was the North Carolina Cherokees who possessed proper certificates exempting them from removal. When the army began the forced removal of Cherokees from North Carolina on June 12, 1838, most Cherokees submitted peacefully to arrest and deportation. Some families with white members held dual citizenship in North Carolina and the CN and were exempt from removal. There were formal citizenship laws that authorized whites married to tribal citizens to become CN citizens. In North Carolina, if the head of the household was listed as white, the spouse was Cherokee and the children mixed-blood. All family members were North Carolina citizens, could legally hold land and were exempt from removal. Other Cherokees, mostly the old and sick, obtained emigration waivers. Many more Cherokee families hid in the Snowbird and Hanging Dog Mountains to escape troops. Along the Valley River, John Welch, Gideon Morris, Junaluska, Wachacha, Nancy Hawkins and other exempted Cherokees concealed, fed and supplied fugitives. Despite aid, the Cherokees who hid suffered losses to starvation and disease after months in the mountains. The third circumstance is the North Carolina Cherokees who were members of Oochella's Band. The Cherokees of Nantahala Town, located in the lower Nantahala River Valley, were a group that fled to the mountains when federal troops and state militia came to the mountains to capture Cherokees in June 1838. Led by Oochella, the Nantahala fugitives evaded the troops for months. The army feared that Oochella's band might turn to guerilla warfare, and returned in September 1838 to pursue them. The troops eventually captured dozens of Cherokees, including Oochella's old neighbor, Tsali, and his extended family. When Tsali, his sons and sons-in-law killed two of their captors and escaped, the military sweep intensified. Other Cherokee fugitives, who feared the manhunt would escalate into a war, brought in Tsali and his band. "After Tsali, Nantayalee Jake, Lowen and Big George were executed in late November, Col. William S. Foster issued a proclamation that granted amnesty to Oochella and his group," Finger Smith said. Oochella and his band joined the Quallatown Cherokees and helped establish the Wolf Town community, which survives as a modern township. It is also where Finger Smith resides with her Cherokee husband. The fourth circumstance is the North Carolina Cherokees who resisted the removal. By the end of 1838, the majority of Cherokees had made it to Indian Territory, what is now Oklahoma. Those Cherokees who avoided removal by evading the soldiers in their mountain hideouts were dismissed by the War Department as not worth the trouble and expense to remove, and could remain in their homeland. After the military withdrawal, approximately 700 Cherokees resided in and around Quallatown, mostly on property that Thomas had purchased on their behalf. Another 400 North Carolina Cherokees were scattered along the Cheoah, Valley and Hiwassee rivers, making about 1,100 Cherokees in the state. Another 300 or so Cherokees resided in nearby areas of Georgia, Tennessee and Alabama. These included a number of mixed-bloods and whites who were Cherokee only by marriage, the "Cherokee Countrymen." The number of Cherokees remaining in the Southeast then was about 1,400. The fifth circumstance was the North Carolina Cherokees who escaped after being removed. Though the exact number of Cherokees who escaped and returned on foot to North Carolina after the forced removal remains undocumented, many family stories have been recorded. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2016 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2016 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||