|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

March 2016 - Volume

14 Number 3

|

||

|

|

||

|

Artist, Educator

And Soldier Edgar Heap Of Birds On "Dead Indian Stories"

|

||

|

by Scott Wheldon - Cheyenne

& Arapaho Tribal Tribune

|

||

|

In Honolulu for a conference, the artist graciously visited

the museum to give a talk on Jan. 6 to a select group of museum

supporters. Hearing him tell the story about the connection between

his prints and Howling Wolf's painting was a moving experience.

Edgar took the time to answer some questions about the two. Can you talk about the origin of 'Dead Indian Stories,' and

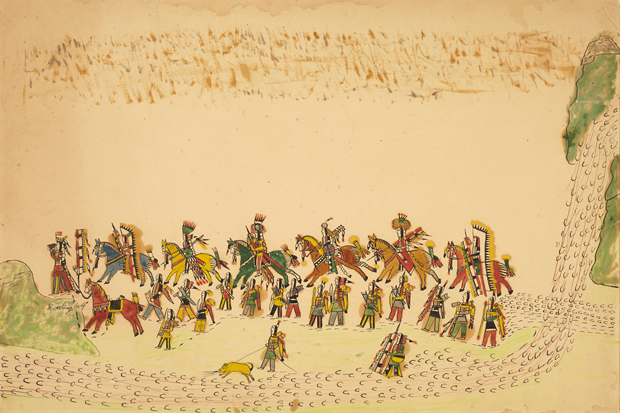

about the meaning behind the prints? It goes back to Howling Wolf's work. It was done while he was

incarcerated in Ft. Marion (Florida, in the late 1800s). He was

a part of the Bowstring Warriors Society, and I'm a leader of the

Elk Warriors Society. The Bowstring and the Elk share the same tipi,

so in 1870 my great-great-grandfather would have been in the tipi

with him. Howling Wolf's father, Eagle Head, and a man named Many Magpies, which later translated to Heap o Birds, then later Heap of Birds, were two of the principle chiefs of the Cheyenne tribe. The other two principle chiefs in the paintings are named Star and Gray Beard. After the Washita massacre of 1868 they were incarcerated as a penalty for fighting against the colonial genocide, and Gray Beard was killed by U.S. soldiers en route to Florida.

My Cheyenne name is Little Chief, a name I inherited from my

uncle Edgar, who inherited it from the first Little Chief, Heap

of Birds' nephew, who was also a Warriors Society member imprisoned

in Florida. The first Little Chief would have been Howling Wolf's

contemporary. The fact that Howling Wolf's drawing is here is amazing.

It shows that while other Warriors Society members died in incarceration,

Howling Wolf survived it. Today when I lecture about Ft. Marion I draw a comparison with

Guantanamo Bay, a space where you have so-called "enemy combatants"

who are sequestered without charges or trial. They can take you

away from your families and your community, then hold your family

hostage in a sense; if they didn't abide by America's rules, the

government might execute the warriors. Abraham Lincoln, for example,

hung 38 warriors himself, Andrew Johnson hung two more. It was a

way for them to keep the tribe "in line," to separate the warriors

from their families, knowing that the warriors might never come

back. When Oklahoma was becoming a state they built three forts, Ft.

Reno, named for Captain Reno, who fought with Custer; Ft. Cantonment;

and Ft. Supply, which was meant to resupply Custer from Ft. Hays

and Ft. Leavenworth in Kansas, so he could come massacre the tribe

at the Washita River. These three forts were built to contain the

tribe, so I say in kind of a satirical way that we were never safe.

For example, if you were in Afghanistan, the forts were not good

for you, as an Afghani. We think of forts as being a good thing,

but it depends on what side of the fort you're on. These were pretty

brutal outposts, the army comes and attacks and murders Native peoples

before the settlers come and create a so-called settlement. My work often deals with political trauma and tragedy that created

America. On the label I wrote about the Statue of Liberty, which

is seen as this symbol of welcoming, but if invited people to share

your house, you wouldn't think that's a good gesture. Everyone is

oblivious to that posture, that you're welcoming everyone to this

country, but it's not your country to welcome anyone to. America

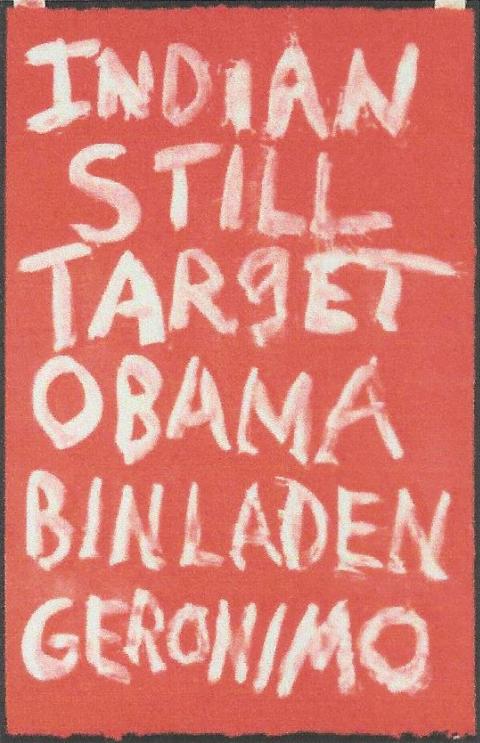

murdered the people that were there. To bring it forward to contemporary time, "INDIAN STILL TARGET

OBAMA BIN LADEN GERONIMO," refers to the fact that the government

referred to Bin Laden as Geronimo. So when they killed him, Obama

said, 'Geronimo is dead,' and everyone cheered. Here we are in contemporary

life and they choose to nickname a hated terrorist an Apache name.

Are we still targets? What about the 'Apache Helicopter' and the

'Tomahawk Rocket?' All these things are so violent, why are they

associated with native people? "INDIO ROAD KILL AGAIN AND AGAIN," goes back to a ceremonial

leader in my tribe whose son was killed in a car wreck by non-Native

people. They ran over his body so many times that they couldn't

put him in a casket, it was pulverized. He was just walking back

to his home, and many Natives die that way on the reservation, just

walking home and getting killed by cars. All of these works are very personal, about the grief and trauma shared by members of the tribe, and the Warriors Society. On the other side of the coin, I'm a professor at the University of Oklahoma, a mentor, an academic, a professional, an artist and a soldier, which I probably take as my most important role, a soldier to protect the tribe. But in the tribe a soldier's responsibility is also the religion. Lately when I'm at gatherings of the whole tribe, they ask me to pray for everybody. I'm just a soldier sitting in the back. I'd rather just sit back, relax and have my dinner, but they call me to the front and say, 'You need to pray for all the people.' I've become an elder, and now that's part of what I do, and I'm proud to do it. Part of that is making art, but you can't just make art about being a happy person, there has to be a testimony about the reality.

Yes, to inform. It's not so much as an assault, it's more for

protection. Art is a cultural apparatus. Take Howling Wolf's drawing,

he was a warrior, his family was hunted and killed in the Washita

massacre, but he wanted to go home. He's not going to make drawings

about killing white people. His job is to protect the tribe and

kill Custer, which they did at Little Big Horn. But while he was

in prison, he couldn't make that drawing of killing Custer. If you

make a drawing of you killing your jailor, you'll never get parole.

Some of the work has become a fiction that a non-Native person would

want to buy. A non-Native person gave him the materials, a non-Native

person, Captain Pratt, was his jailor. Eventually they decided,

'Okay he's rehabilitated, send him back The sad part about that is that this kind of art about the 'good

Indian' doing pastoral work has become a genre. Ledger drawing then

became the birth of Native American art patronage in America and

continues to this day, where by the content of Native art was/is

dictated by non-Natives. It's a way for Native artists to fit into

society and make money. However this sort of self-censorship does

a disservice because the white American public has no clue about

the dysfunction, suicide, teen pregnancy and illiteracy because

all they see are these nice paintings they want to buy. The trading posts and galleries for Native art take 50 percent

of the sales of these pastoral works, thus Native art has been a

profitable business for non-Natives. I have to sort of fight that.

We've been co-opted by this industry, it's about their apparatus

of money making, not the reality of what's happening culturally.

It's difficult to reveal the reality of the damage and all the problems

of tribal life in America, when people see art like this and say,

'Well look here. There's no violence here. All of the lovely baskets

in Santa Fe, Scottsdale, Sedona, don't show this kind of violence,

why did you make that?' Did you know that Howling Wolf's painting was here before

bringing your installation to the museum? No, I didn't know. Jay Jensen, curator of contemporary art had

told me about it and it's amazing that it's here. I'm really proud

to be exhibiting with it. As I said to Jay, there are four chiefs

here, along with Howling Wolf. One of these four chiefs would have

been my great-great-grandfather Heap of Birds. With this painting

Howling Wolf is surviving, fighting a different kind of fight, and

I'm doing these gestures to his prints. I don't fault Howling Wolf for doing this kind of work. My father

was an aircraft factory worker. He raised six kids, and worked three

jobs so that I could go out and make this and be in the leadership

ceremony. I don't fault what the older men had to do to allow me

to survive and take breath. I understood some of the prints only when you explained them.

Others are immediately understandable, like "HAPPY TO DONATE WHAT

YOU TOOK." How do you decide how explicit your message is? The artist's material does a little bit of that, but I write

this way because I hope that people can interpret the work with

their own ideas. I want the work to join forces with the viewers'

imaginations. I have a lot of respect for the viewer, so the work

doesn't need to be didactic. I know about a boy who got killed in San Francisco by a bus,

and I'm sure that when his parents saw "INDIO ROAD KILL AGAIN AND

AGAIN" they were thinking about their son who died in San Francisco.

There are other ways for people to relate to the work, which brings

us back to not thinking about the idea of being Native as being

a disadvantage story or a pastoral story, but a human story. We

should all have a way to enter the work. By leaving it somewhat ambiguous I'm leaving the door cracked

open. If I made it too explicit, you could just digest it and eject

it, you don't have to really consider it. I hope that people look

at the work, and when they enter it they can relate it to themselves. I also believe in a fragmentary experience where you can carry

some of this with you, and then tomorrow, or next week, or next

month, something might happen to you that makes you think of this

work. It's not a capsule in which there is one narrative pill, it's

more of a fragmentary experience that people can have. That's why

the prints are made in this mysterious method. These are all done

on Plexiglas, they're all made singularly and I'm painting backwards

on clear glass, which are then printed up. It doesn't look quite

so clear, like the meanings of each work might not be so clear. Except for "HAPPY TO DONATE WHAT YOU TOOK," which Jay requested,

how did you decide on what prints to use for this installation? I thought these works were compatible with each other. I usually

do installations of 16 prints, but I always do it in multiples of

four. Four is a very important ceremonial number for the Cheyenne,

it relates to the solstice and equinox of the earth. On being deliberate with numbers, is there a reason why you

have chosen to have six words on each print? It has become a trait of mine, it's somewhat mysterious. I go

back and think of my name, Heap of Birds, that has a certain cadence

that I've been living with all my life. Looking at each of these

prints, like "WILL GET ILL FROM STATIC BELIEFS" or "INDIO ROAD KILL

AGAIN AND AGAIN," I think of these messages as being made up of

two sets of three words. As a young artist I was on the east coast, and I was in New

York all the time. At that time, from '75 to '81, The Talking Heads

were big. We were all disciples of The Talking Heads. Stop Making

Sense, and Fear of Music, all these things that David Byrne did

I really liked a lot. I probably ended up inheriting some of his

rhythm. I am really an artist that was reared in New York and the

contemporary art of the 80s. I was in the middle of a lot of social

discourse of that time. What other artists, contemporary or otherwise, would you

say influenced your work? The biggest one for me when I was a young guy was the performance

artist Vito Acconci. He gave a talk at my school when I was getting

my masters degree in Philadelphia, and I've since showed with him.

In Wichita, Kan., Blackbear Bosin, a Comanche-Kiowa painter, was

my mentor. He was great to have as a mentor, he showed me how to

be an artist. We did an Instagram post about your installation, which generated

positive comments from people across the country who had either

taken a class from you or have heard you speak. It seems like you

have a wide reach as an educator. Is education a big priority in

your professional life? Yes, and you know I don't have a gallery. I've never had one, but as one of my colleagues told me I probably couldn't have had as big of an educational reach as I've had if I had a gallery. At this point of my career I would wish to be represented by a gallery, but my mission is to communicate, not to sell, and education is the best way to communicate.

Edgar

Heap of Birds Edgar

Heap of Birds | Brett Graham | Enrique Chagoya |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2016 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2016 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Now

on view in the gallery of the Arts of the Americas is a print series

by Oklahoma-based artist Edgar Heap of Birds. The text-based works

are a scathing indictment of crimes committed against Native Americans

and hang next the museum's mid to late 1870s painting by Cheyenne

warrior Howling Wolf, who became a proficient artist in the Ledger

style while imprisoned in Ft. Marion, Florida, in 1875.

Now

on view in the gallery of the Arts of the Americas is a print series

by Oklahoma-based artist Edgar Heap of Birds. The text-based works

are a scathing indictment of crimes committed against Native Americans

and hang next the museum's mid to late 1870s painting by Cheyenne

warrior Howling Wolf, who became a proficient artist in the Ledger

style while imprisoned in Ft. Marion, Florida, in 1875.

I

read that you once said, "Native peoples have chosen art as their

cultural tool and weapon." As a soldier, do you consider these prints

your weapon?

I

read that you once said, "Native peoples have chosen art as their

cultural tool and weapon." As a soldier, do you consider these prints

your weapon?