|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

June 2015 - Volume 13

Number 6

|

||

|

|

||

|

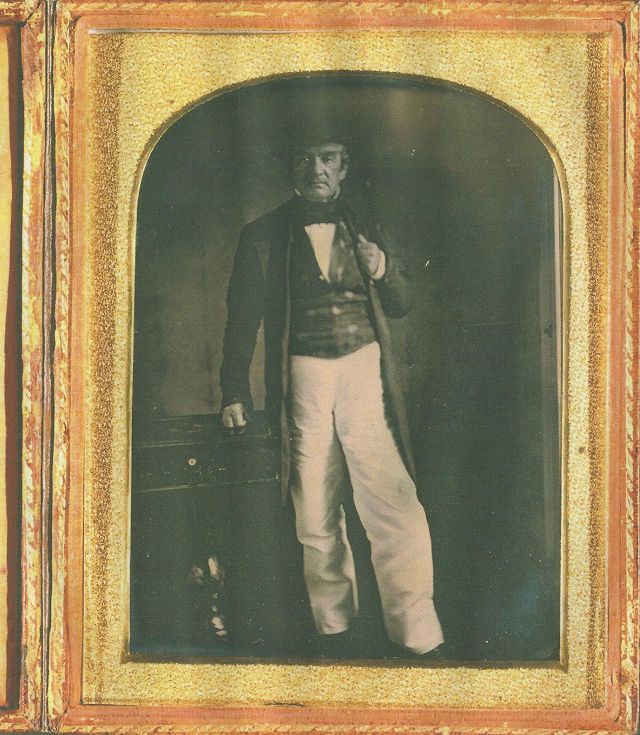

The Cherokee Leader

Who Paved The Way For MLK

|

||

|

by Steve Inskeep for

the Washington Post

|

||

|

Steve Inskeep is a co-host of NPR's "Morning Edition" and the author of "Jacksonland: President Andrew Jackson, Cherokee Chief John Ross, and a Great American Land Grab." Studying the 19th century is like being a parent. You have flashes of recognition that your children behave as you once did. You wonder if your ancestors acted like you, too. Similar patterns emerge when researching the political ancestors of modern leaders. The 1820s and 1830s — the era when our modern democracy began to take shape — were full of recognizable figures, such as a Georgia governor who fulminated in 1825 against a perceived conspiracy by Washington elites. (He was paranoid that Supreme Court justices and an untrustworthy president would free his state's slaves. Today his political positions are outdated, but his rhetoric lives on.) Even more striking is an early-19th-century civil rights leader. Nobody called him that, of course. But John Ross fought for his rights with tactics that perfectly prefigured America's 20th-century civil rights battles. What people actually called Ross was an Indian. Eventually, he was the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, resisting efforts to drive his people out of their historic homeland in north Georgia and the surrounding states. Seeking to influence a democratic society, John Ross of Georgia used tactics similar to those of Martin Luther King Jr. of Georgia. Their parallel experiences say much about what has and hasn't changed in America. Ross was of mixed race. His ancestors included Scottish traders who lived among Cherokees in colonial times and married Cherokee women. Born in 1790, he grew up in a changing world. Cherokees had been an independent nation for centuries but were overwhelmed by spreading white settlement in the early 1800s. Unlike many Indian leaders, who rebelled against the new order, the Cherokees decided to join it. They signed treaties accepting the protection of the federal government. They adopted white styles of clothing, religion and business. Some — including Ross — copied the white use of enslaved laborers. Ross's English-language skills and education suited him for leadership during this time of adaptation. "We consider ourselves as a part of the great family of the Republic of the U. States," he wrote early in his career. He aspired to make the Cherokee Nation a U.S. territory or state. That was never likely. White settlers wanted Indian land, not the Indians on it. Today, schoolchildren learn the ending of the story: the Trail of Tears in 1838, when 13,000 Cherokees were forced to move west to what is now Oklahoma. Thousands died during that time — the victims of a ruthless, government-sponsored campaign of segregation. Less well known is the long prelude to this disaster. Ross spent more than 20 years fending off expulsion. His epic battle against Andrew Jackson, the iconic hero of the United States' emerging democracy, did much to shape the nation we inherited. As a young man, Ross joined the Cherokee Regiment, raised to assist the United States in the War of 1812. The unit fought in an Army commanded by Gen. Jackson. When the war ended, Ross highlighted his military service. Joining a Cherokee delegation to Washington, he argued that Cherokees had proved their "attachment" to the United States in war, so their rights must be respected. Ross also recruited newspapermen, who described that service in print. He was pioneering a tactic that African Americans would later use. Frederick Douglass urged black men to enlist in the Civil War and earn the freedom of black slaves ("Let us win for ourselves the gratitude of our country, and the best blessings of our posterity through all time"). A much-decorated black regiment called the Harlem Hellfighters returned from World War I expecting equality. This didn't always work — African Americans, of course, would wait decades before winning civil rights — but it worked for Ross in 1816. Federal officials handed Cherokee heroes ceremonial rifles to commemorate their service and awarded them a temporary victory: The government blocked a plan to seize 2 million acres of Cherokee land. That plan had been orchestrated by their former commander, Jackson, who was in charge of military affairs in the South. In 1828 Jackson was elected president. He was on his way to founding the Democratic Party, and he was profoundly expanding presidential power. He was also determined to move numerous Indian nations west to make way for white settlement. He said it would be better for Indians to be "free from the mercenary influence of white men." Some Indians agreed that they were endangered by white culture, greed and guns, and had already moved. But most did not. To lobby against this separate-but-unequal scheme, Cherokees under Ross started a newspaper, the first ever published by Native Americans. Just as later generations of African Americans would make themselves heard in the pages of the Chicago Defender, Cherokees spoke through the Cherokee Phoenix. Copies were mailed to other newspapers, and its articles were reprinted widely, spreading Cherokee perspectives. And like later civil rights leaders, Ross found white and religious allies. He appealed to white missionaries who proselytized to Native Americans. The Cherokees flipped the missionaries, who spread word back to the white population that Cherokees were Christian, civilized and worth defending. They activated a powerful network of preachers, publishers and politicians. One Christian writer and activist wrote two dozen articles against removal in the National Intelligencer, the era's nearest approximation of the Washington Post. He even encouraged a national movement of women, who could not vote but petitioned Congress. The agitation was not quite enough. In 1830 Congress narrowly passed, and Jackson signed, the Indian Removal Act, offering transportation and land to natives who "voluntarily" moved west of the Mississippi. Yet Ross refused to give up. Facing pressure from Georgia, which imposed racist laws on the Cherokee Nation, Ross sued, much as the NAACP later sued in Brown v. Board of Education. Ross scratched together money for a legal team. He personally made a hazardous trip to deliver a summons to Georgia's governor, fearing that no one else could be relied upon to do it. The Supreme Court threw out the case on a technicality, so Ross pursued another case, Worcester v. Georgia , which succeeded in early 1832. Georgia had imprisoned two white missionaries who supported the Cherokees. Chief Justice John Marshall's magisterial opinion said the missionaries must be freed: Georgia had no right to impose its laws in the Cherokee Nation, where Cherokees were "the undisputed possessors of the soil, from time immemorial." Incredibly, Marshall's ruling came to nothing. Georgia refused to recognize it. Jackson denounced it and used sharp political maneuvering to make it go away. (His administration quietly arranged for the missionaries to be freed, making the court case moot, and he simply ignored Marshall's broader finding.) Denied the shelter of the law, Ross steeled his people for passive resistance, in the spirit of the nonviolent civil rights demonstrators of the 1960s. Ordered to leave in the spring of 1838, Cherokees instead planted crops as if they'd be around for the harvest. The government sent soldiers to begin expelling the tribe. In defeat, Ross had one consolation: The Army's rousting out of peaceful Indians fixed this tragedy in our national memory. "You can expel us by force," Ross wrote in 1838, ".?.?. but you cannot make us call it fairness." Passive resistance also yielded some practical results. Horrified by the prospect of a humanitarian disaster, federal officials at least improved the terms of removal. Ross's Cherokee government was promised more than $6 million for its land, probably a fraction of its real value but still a substantial sum. In exchange, Cherokees agreed to organize their own journey west rather than going at bayonet point. Ross billed the government for the Cherokees' travel, charging every cent he could. The final departure of Cherokees and other native nations made way for the creation of what we call the Deep South, with its economy based on plantations worked by black slaves. On this same ground, more than 100 years later, a new movement for minority rights emerged. One reason Cherokees could not prevail is that American institutions were less developed than they later became. Imagine if, in 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower had defied or undermined Brown v. Board of Education. There was a deeper reason, though. While American democracy was expanding in the early 19th century to embrace nearly all white men, including those from poor backgrounds, like Jackson, it remained an openly racist democracy: government "on the white basis," as Jackson's political heir Stephen Douglas later put it during the Lincoln-Douglas debates. In the 1830s, even some of the Cherokees' political sympathizers saw them as an inferior race whose doom was inevitable. The great Sen. Henry Clay publicly declared that honor required the United States to uphold Indian rights, but he privately said that Indians' extinction would be "no great loss to the world." Later generations of Americans began to confront that underlying racism, recognizing that government "on the white basis" must be wrenched onto a broader and stronger foundation. This made it possible for minority groups to secure their rights using tactics that did not quite work for John Ross. We are indeed repeating the patterns of our ancestors, but we are gradually enjoying different results.

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2015 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2015 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||