|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

May 2015 - Volume

13 Number 5

|

||

|

|

||

|

10 Ways To Boost

Tribal Language Programs

|

||

|

by Christina Rose -

Indian Country Today Media Today

|

||

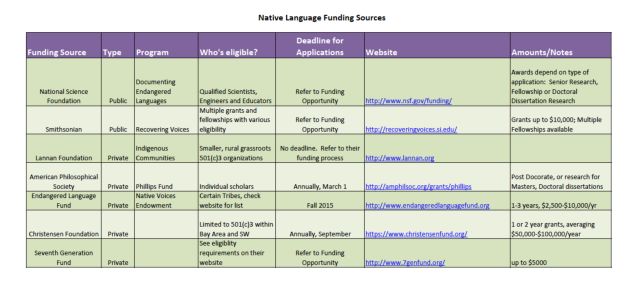

The traditional arts of building canoes and fishing traps, making rabbit fur blankets, and pine nut picking are celebrated in the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California’s Language Program. Through these activities, the tribe’s youngest children are not only learning their language, they are becoming cultural leaders in their communities. Community participation is the biggest challenge in revitalizing tribal languages, and a recent podcast highlighted the successful efforts of two tribal language programs, The Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California and the Puyallup of Washington State. Three speakers, Lisa Enos, Washoe, coordinator of the Washoe Language Program, and the Twulshooteed (Puyallup) instructors, Amber Sterud-Hayward and Brittany Corpuz, both Puyallup of Washington State, brought insights from their programs, and offered nine ways to encourage language learning and cultural revival, with minimum funding. Like so many other tribes, the Washoe are facing losing their original languages. Of 1,500 registered Washoe tribal members, there are only eight fluent speakers of the Wasiw language, all of them over 70. For the Puyallup, there are only five certified Level One speakers among the 4,800 tribal members. Level One speakers are not fluent, but in the process of learning the language. Funding

Elders

Cultural Activities When the children and the elders made a rabbit fur blanket, “a buzz went through the community because it hadn’t been done in 50 years,” Enos said. “What our children are learning, they bring back and teach to the community.” The children have made snowshoes and canoes, and one of the fathers helped the children make baskets. The grandparents are selling the moccasins the children make. “One night, the kids were teaching their parents hand games, and the officer patrolling the area saw a lot of cars at Head Start. The next thing you know, our tribal officer sat down and played hand games with the kids, and that was exciting because they get to see the officials in a different light,” Enos said. Community Involvement Enos said the activities are igniting a passion in the community that they weren’t able to inspire with nightly classes for the adults. “We had sporadic involvement, but now it is really catching like wildfire,” Enos said. “What the children are learning in school and afterward has really flooded over into the families and the community.” The high school youth now speak the Washoe language at basketball games, and the younger ones are using it in gym, which has inspired the adults. “It’s all natural. All the kids are asking how to say their names in Washoe. The more it is heard, the more involvement we get,” Enos said.

Books Handouts for parents Curriculum Development The program was updated in 2014, when new staff members Chris Duenas, media developer; Zalmai Zahir, Twulshootseed language consultant; and Hayward put forth new efforts that resulted in a program that modeled language use in daily life. Hayward said the original use of simple phrases wouldn’t produce any speakers “because you are telling people what they should say.” They began asking tribal members what they wanted to say. Hayward said language and lifestyle should be related. A school setting requires one sort of vocabulary, a work setting another, and at home, yet another. “Our curriculum has literally turned into exactly what people want to say. Some are good at hearing audio, some people want video to see how your mouth forms, some want it written down, and some want it phonetically. We just decided we had to give people whatever they needed to speak the language, and we saw a big change.”

Using Media Social media has played a huge part for the Puyallup language program. Videos made for tribal members range from simple to more advanced. “That has been a huge push within our community,” Hayward said. Hayward said people were intimidated by subtitled videos produced in the beginning. “So we switched to making little Facebook videos that were partially in Twulshootseed (the Puyallup language) and partially in English. Now people from all over are looking at those, and people practice at home.” Games Free Resources The program was provided by the Eastern Region Training and Technical Assistance Center and will soon be available at the Administration for Native Americans website along with previous programs about language revitalization. |

|||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2015 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2015 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||