|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 2014 - Volume

12 Number 12

January 2015 - Volume 13 Number 1 |

||

|

|

||

|

One Feather: A Lakota

Life

|

||

|

by Gerald One Feather

with Tom Katus

|

||

| Editor’s Note: The following autobiography

is a result of a conversation between Gerald One Feather and Tom Katus.

The concepts expressed are One Feather’s. Katus assisted in arranging

and editing the stories, with One Feather’s input and final approval.

I was born July 10, 1938, in the Pine Ridge Hospital, the oldest child of Jackson “Joe” One Feather and Elva (Stinking Bear) One Feather. There were four brothers in the family: Morris, who was born in 1941, the twins Kelmar and Delmar who were born in 1952, and myself. My father was born and raised in Kyle on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. After he married my mother, they settled in Oglala in the Stinking Bear Tiospaye compound. I resided there throughout my youth and later established my own home where I married and had my children. I lived in a log home on the compound. My mother lived in a small house in the compound and lived to be 88 years old when she died in 2002. There have been three intertwining themes in my life: the spiritual, the political and the academic. I have been fortunate to be selected and elected as a leader in each of these fields. My Father’s Generation My father, Jackson One Feather, better known as “Joe,” was born in 1915 and died in 1971. He attended the Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school in Genoa, Nebraska, and graduated from the eighth grade. When the first tribal government council was established in 1934 as mandated by the Indian Reorganization Act, my father was elected a district representative from the Oglala Junior Sub-district. He subsequently served for 23 years on the Oglala Sioux Tribe council and also served as a tribal judge. He owned some cattle, but was best known for his ability as an eyapahaya (announcer). He announced at both traditional powwows and contemporary tribal events. When Bobby Kennedy was campaigning for president in 1968, he visited Calico Village near Oglala and met my father. In 1995, I took a photo to U.S. Representative Joe Kennedy of our fathers when they met in 1968, as I wanted to reestablish that cycle of friendship that began in 1968. At that time, the national press was following Bobby Kennedy’s campaign. He visited a very poor family in a log cabin. When he came out of the cabin, he was crying about the desperate conditions in which he saw the family. News of this compassionate demonstration of emotion spread like wildfire throughout the reservation. Kennedy won an overwhelming vote on Pine Ridge, which helped him win the South Dakota primary, even though Hubert Humphrey—who was born in the state—was his major competitor. South Dakota and California were the final presidential primaries in June 1968. A Kennedy aide named Jeff Smith was coordinating get-out-the-vote efforts on Pine Ridge. At about 9:00 PM., he received a telephone call from the senator. Kennedy had just found out that he’d won the state and asked Jeff how he had done on Pine Ridge. Smith replied, “Well, Senator, the reservation is very rural so the results are just starting to come in. However, Pine Ridge Village voted 672-2 for you.” There was a pause on the other end of the line, and then in a deadpan tone Kennedy said, “How in the world did we lose two votes, Jeff?” Two hours later, following his victory speech in California, Kennedy was assassinated. My Grandfather and Other Ancestors My grandfather was Moses One Feather, also from Kyle. Like his son, Moses was a famed eyapahaya. He died after a Fourth of July celebration in Kyle. My father told me that after my grandfather finished his announcing activities at the celebration, he got off his horse and dropped dead. My ancestors on my mother’s side were medicine men. Charlie Stinking Bear was my mother’s father. His father, also named Stinking Bear, married two sisters of Chief Standing Elk. The sisters were Northern Cheyenne and also had some Yanktonai heritage. Stinking Bear was a noted bear medicine man and used a bear paw in his healing ceremonies. College In the fall of 1956, a boyhood friend and neighbor, Calvin Jumping Bull, came to my house and asked, “Do you want to go to college? I’m driving to Dakota Wesleyan University to enroll.” I said, “I don’t have any money.” Calvin responded, “Neither do I. Jump in.” I had $20 on me, and we stopped at Wanblee and picked up our friend Fred Mesteth who also protested that he didn’t have any money. Calvin also assured him, “Don’t worry about it. Come along.” By 9:00 PM that evening, we arrived at the Dakota Wesleyan University dormitory. The counselor, Fred Lopez, who was also the football coach, said we could stay overnight in the dormitory and sort things out in the morning. When we got up, he asked us, “Do you guys play football? If you do, you get free room and board.” I had played football in high school at Pine Ridge. I took him up on his offer and became a linebacker on the university’s team. That fall, George McGovern, formerly a professor at Dakota Wesleyan, ran for the US Congress. Together, with another student named Sam Dicks, we alternately drove McGovern all over the state. On election eve, I drove him to a television station in Sioux Falls where he made a final appeal. He had started campaigning with support from only a third of potential voters, trailing incumbent Harold Louvre in the polls. McGovern’s door-to-door campaigning in virtually every town in South Dakota gave him a “squeaker” win. The next year, I transferred to the University of South Dakota because I was given a research scholarship; the university’s Government Research Bureau paid me $1 an hour. I was a political Science major, and my adviser was Professor William O. “Doc” Farber.

On June 24, 2001, I was honored when my friend Tom Brokaw returned to South Dakota as a guest speaker at Oglala Lakota College’s commencement. Brokaw helped OLC launch the Gerald One Feather Faculty Endowment Fund. He personally gave $25,000 to the Fund and encouraged others to contribute. Today, that Fund is endowed at $1 million. Encouraging others to contribute, Brokaw stated: Although I have been gone from South Dakota for many years, I remain spiritually and intellectually connected to my home state, especially the many friends who elected to stay and make it a better place. One of them, Gerald One Feather of the Pine Ridge reservation, is a special hero of mine. We met as undergraduates at the University of South Dakota, and we’ve stayed in touch through the years. He has never given up on his mission of providing first-rate education for the Oglala people. Meredith and I intend to support this worthy effort, and I hope you will as well. I can assure you your efforts will be well rewarded (Brokaw, 2001). The first Gerald One Feather Faculty Chair is now occupied by retired tribal judge Patrick Lee. Spirituality I was raised by spiritual parents, and both my grandfather and father on my mother’s side were medicine men. There was great turmoil on the Pine Ridge reservation in the 1970s. One day, my friend Amos Badheart Bull came by and picked me up. We drove to a hill where we had previously prayed. We both saw a spirit on the top of the hill. Amos said, “You are supposed to go to him. I’ll stay in the car.” I went to the hill and prayed to the spirits to give me guidance on what could be done to help the people. On the way down the hill, I kicked a bottle that was partially buried in the soil. I picked it up and found it to be a sealed wine bottle. Despite the fact that the seal was not broken, the bottle was empty. I took this as a sign that I should convince the tribal council to ban alcohol on the reservation. I brought this proposal to the council. It was very controversial and by a one-vote margin, the tribal council banned alcohol on the reservation, which has stood for the past 30 years. Later on that same year at a hill near Calico, I fasted and prayed for four days. On the last day just before daybreak, four figures appeared to me. One had a feather hanging from his arm. He said he was Crazy Horse and that I should work to support the return of the Black Hills to the people. The next figure had one feather sticking straight up at the back of his head. He said, “I am Sitting Bull. You are here to help revive the rights of the Lakota Nation.” The third figure wore a headdress. This was Red War Bonnet, who had the power to organize the tiospayes in the 1870s. The fourth figure had a blanket around him. He said, “I am Matosnimna. I am the medicine man who was with Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull and served as their surgeon general at the Battle of Greasy Grass. I want you to help the traditional tiospaye communities to develop themselves.” Since that vision, I have attempted to carry out the wishes of the spiritual leaders. I continue to support the return of the Black Hills to the Lakota and believe that this will indeed occur. I have fought for these rights, including representing our people at the United Nations in Geneva. I have tried to carry out Sitting Bull’s directions by reviving the traditional young women’s ceremony and teenage boys’ vision quest. Traditionally, these ceremonies were practiced but were nearly lost. My wife Ingrid and I have been involved in reestablishing these ceremonies for young people who, in puberty, are transitioning from girls and boys to young women and men. We have carried out these ceremonies for the past 13 years, and more than 60 young women and 50 young men have participated in them. We are hopeful these ceremonies will continue to be revived to help bring back the Lakota Nation. If we lose these ceremonies, coupled with the loss of our language, we will lose our culture. It is up to the next generation to save us from this loss of culture. I have also tried to carry out Matosninna’s vision by attempting to reestablish the Lakota elders’ traditional form of government known as omniciye (forum). Together with Dr. Elgin Bad Wound, then president of Oglala Lakota College, I coordinated a year-long forum on the Lakota elders’ omniciye. Forty-two Lakota elders participated in the forums over the course of a year. We had 531 participants in the seven forums, and we also broadcast them over KILI Radio to an estimated 184,891 listeners (One Feather and Bad Wound, 1992). The report on this forum, which had been funded by the Northwest Area Foundation, had sufficient impact to prompt the foundation to award another $300,000 over five years in an attempt to implement traditional government. As a result, there are now numerous Oglala extended families practicing traditional tiospaye government on the reservation.

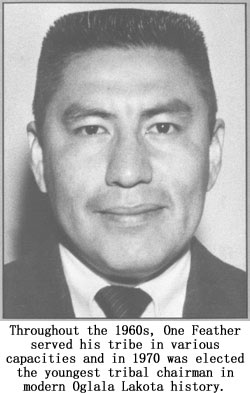

We have just completed a four-year cycle of Sun Dances and will start another cycle this next summer. In the past, any individual who wanted to dance was welcome to participate in the ceremonies. However, beginning this summer, we are reverting to the old custom where each tiospaye elects dancers to represent the entire tiospaye. Politics Like my father before me, I ran for the Oglala Sioux Tribal

Council and won as a district representative from the Oglala Junior

District. That was in 1960. Subsequently, I spent 14 years in tribal

government as a councilman, a member of the executive committee,

as secretary, treasurer, and as the Fifth Member. In 1970, I was

elected tribal chairman at the age of 32. I was the youngest chairman

to ever be elected to the Oglala tribal government as established

under the Indian Reorganization Act.

Perhaps because of my early involvement in George McGovern’s

campaign as one of his student drivers, and due to my election to

the chairmanship of the Oglala Sioux Tribe in 1970, I was elected

to the South Dakota Democratic Party to serve on the Democratic

National Committee. During meetings at the DNC, I met Terry Stanford,

who was then governor—and later a US senator—of North

Carolina. He invited me to Duke University where I spent a week

interacting with both students and faculty, as well as the governor.

Oglala Lakota College (OLC) was one of the first tribal colleges in the United States. It was founded in March of 1971 while I was still tribal chairman. Thomas Shortbull, current president of OLC, recently reflected on my role in starting the college: Mr. One Feather is one of the founding fathers of the college. A true visionary who back in the early 1970s foresaw that for the college to be successful, we would need to create a decentralized approach to higher education. And that is why today we have college centers in every district of this 5,000 square mile reservation. Before the innovation of computerized communication, Gerald knew that distance learning was a need. He understood this long before the creation of the current distance learning technology that connects our ten college centers with each other and with the world. Mr. One Feather has been a lifetime advocate of higher education

for the Lakota people. Gerald and others felt that, for the reservation

to truly make progress, the tribe had to take control of its affairs

in all areas. Due to his vision, the college was created

and is thriving today…[He] currently serves as a member of

the elder advisory committee for Oglala Lakota College (Shortbull).

Together with other tribal leaders, we started the college with volunteer professors. Even though I was extremely busy as tribal chairman, I believed so deeply in the college that I taught two courses, American government and world history, the first year it began. I served as chairman of the board at OLC for 10 years. In the spring of 1972, I was defeated as tribal chairman in my reelection attempt by Dick Wilson. The day after I left the tribal chairmanship, I was offered a position at Black Hills State University. Along with Professor Keith Jewett, I helped found the university’s Indian Studies Department. We were able to secure a $100,000 allocation from the South Dakota state legislature to start the Indian studies program. I commuted from Oglala to the Spearfish campus (300 miles round trip) three days a week and assisted in the development of the department, including doing research, teaching, and recruiting students. Prior to receiving accreditation from the Higher Learning Commission, OLC college courses were accredited through Black Hills State University. Today, there are approximately 200 Native students at the university. In 1973, I helped start the American Indian Higher Education

Consortium (AIHEC). At the time AIHEC was comprised of the first

six tribal colleges: Navajo Community College (later Diné

College) in Tsaile, Arizona; Lakota Higher Education Center (now

OLC) in Kyle, South Dakota; Sinte Gleska College (later Sinte Gleska

University) in Rosebud, South Dakota; Turtle Mountain Community

College in Belcourt, North Dakota; Standing Rock Community College

(now Sitting Bull College) in Fort Yates, North Dakota; and DQ University

in Davis, California.

References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2014 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2014 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

I

used to tease Tom Brokaw that I met his wife Meredith before he

even knew her. She was in one of my classes. I subsequently met

Brokaw on campus. We went out for coffee a few times and became

friends. Throughout the years, we stayed in touch. He visited me

in South Dakota a few times when he was an NBC newsman, and

I visited him in Washington, DC when he was the Washington bureau

correspondent for NBC.

I

used to tease Tom Brokaw that I met his wife Meredith before he

even knew her. She was in one of my classes. I subsequently met

Brokaw on campus. We went out for coffee a few times and became

friends. Throughout the years, we stayed in touch. He visited me

in South Dakota a few times when he was an NBC newsman, and

I visited him in Washington, DC when he was the Washington bureau

correspondent for NBC. In

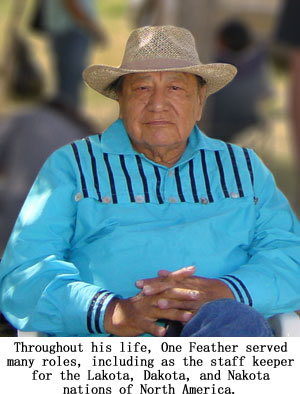

1995, a group of elders came to me and told me that I had been selected

to be the staff keeper for 33 Lakota/Dakota/Nakota nations in Canada

and the U.S.A lifetime appointment, the staff keeper organizes a

meeting of traditional leaders every year, as well as a traditional

Sun Dance. Since my selection, these meetings have occurred annually,

alternately in Canada and the US When I asked the elders how I had

been selected, they responded, “We had a sweat, and we asked

the spirits for guidance. They selected you.”

In

1995, a group of elders came to me and told me that I had been selected

to be the staff keeper for 33 Lakota/Dakota/Nakota nations in Canada

and the U.S.A lifetime appointment, the staff keeper organizes a

meeting of traditional leaders every year, as well as a traditional

Sun Dance. Since my selection, these meetings have occurred annually,

alternately in Canada and the US When I asked the elders how I had

been selected, they responded, “We had a sweat, and we asked

the spirits for guidance. They selected you.” Later,

I encouraged the tribe to take over its own police force from the

BIA. I helped establish the Oglala Sioux Tribal Public Safety Commission

and served as executive director for eight years. I helped found

the National Tribal Chairman’s Association, served as a vice

president of the National Congress of American Indians, served on

the Board of the American Friends Service Committee, and served

on the South Dakota Indian Affairs Committee during the George S.

Mickelson and Walter Dale Miller administrations. In 1995, I was

honored to be selected as a Petra Foundation Fellow. Each year the

fellowship honors four individuals who are “committed to resisting

intolerance, removing barriers to achievement, freeing the human

spirit and contributing significantly to the autonomy of individuals,

groups and communities” (Hamilton, 1995).

Later,

I encouraged the tribe to take over its own police force from the

BIA. I helped establish the Oglala Sioux Tribal Public Safety Commission

and served as executive director for eight years. I helped found

the National Tribal Chairman’s Association, served as a vice

president of the National Congress of American Indians, served on

the Board of the American Friends Service Committee, and served

on the South Dakota Indian Affairs Committee during the George S.

Mickelson and Walter Dale Miller administrations. In 1995, I was

honored to be selected as a Petra Foundation Fellow. Each year the

fellowship honors four individuals who are “committed to resisting

intolerance, removing barriers to achievement, freeing the human

spirit and contributing significantly to the autonomy of individuals,

groups and communities” (Hamilton, 1995). Involvement

in the Tribal College Movement

Involvement

in the Tribal College Movement I

have continued to be active as an elder adviser to President Shortbull.

I am strongly encouraging him to establish a Lakota language institute

to be certain we retain and expand the Lakota language. From the

beginning, OLC has had a Lakota studies department. However, this

language institute would be more comprehensive and would build on

the Lakota Studies Department’s work of Lakota word and curriculum

development. I feel it is imperative that we develop a Lakota K-12

curriculum and insist that it be taught in all our schools on the

reservations, and be available in urban settings as well.

I

have continued to be active as an elder adviser to President Shortbull.

I am strongly encouraging him to establish a Lakota language institute

to be certain we retain and expand the Lakota language. From the

beginning, OLC has had a Lakota studies department. However, this

language institute would be more comprehensive and would build on

the Lakota Studies Department’s work of Lakota word and curriculum

development. I feel it is imperative that we develop a Lakota K-12

curriculum and insist that it be taught in all our schools on the

reservations, and be available in urban settings as well. In

the spring of 1973, I visited my friend Tom Katus who had taken

a position as a program officer with the Phelps Stokes Fund in New

York City. Together we visited the Ford Foundation and within 10

days secured a grant for $25,000 to launch AIHEC, even before it

was officially organized as a 501(c) 3. The Phelps Stokes Fund served

as “fiscal agent” for this grant, but it was totally administered

by the six colleges. We used the grant for a series of organizing

meetings. I served as the first chairman of AIHEC throughout its

first decade. Today, AIHEC has 37 tribal colleges and universities

throughout the United States, and one in Canada.

In

the spring of 1973, I visited my friend Tom Katus who had taken

a position as a program officer with the Phelps Stokes Fund in New

York City. Together we visited the Ford Foundation and within 10

days secured a grant for $25,000 to launch AIHEC, even before it

was officially organized as a 501(c) 3. The Phelps Stokes Fund served

as “fiscal agent” for this grant, but it was totally administered

by the six colleges. We used the grant for a series of organizing

meetings. I served as the first chairman of AIHEC throughout its

first decade. Today, AIHEC has 37 tribal colleges and universities

throughout the United States, and one in Canada.