|

The

spectacular but endangered California Condor is the largest bird

in North America. These superb gliders travel widely to feed on

carcasses of deer, pigs, cattle, sea lions, whales, and other animals.

Pairs nest in caves high on cliff faces. The population fell to

just 22 birds in the 1980s, but there are now some 230 free-flying

birds in California, Arizona, and Baja California with another 160

in captivity. Lead poisoning remains a severe threat to their long-term

prospects. The

spectacular but endangered California Condor is the largest bird

in North America. These superb gliders travel widely to feed on

carcasses of deer, pigs, cattle, sea lions, whales, and other animals.

Pairs nest in caves high on cliff faces. The population fell to

just 22 birds in the 1980s, but there are now some 230 free-flying

birds in California, Arizona, and Baja California with another 160

in captivity. Lead poisoning remains a severe threat to their long-term

prospects.

At a Glance

|

Habitat

|

|

Food

|

|

Nesting

|

|

Behavior

|

|

Conservation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mountains

|

|

Carrion

|

|

Cliff

|

|

Soaring

|

|

Critically Endangered

|

|

Measurements

Both Sexes

Length

46.1–52.8

in

117–134

cm

Wingspan

109.1 in

277 cm

Weight

246.9–349.2

oz

7000–9900

g

Relative Size

Larger than

a Bald Eagle; this is the

largest bird in North America.

Other Names

Condor de Californie (French)

Condor californiano, Buitre (Spanish)

|

Cool Facts

- What’s in a name? The name “condor” comes

from cuntur, which originated from the Inca name for the Andean

Condor. Their scientific name, Gymnogyps californianus, comes

from the Greek words gymnos, meaning naked, and refers to the

head, and gyps meaning vulture; californianus is Latin and refers

to the birds’ range.

- In the late Pleistocene, about 40,000 years ago, California

Condors were found throughout North America. At this time, giant

mammals roamed the continent, offering condors a reliable food

supply. When Lewis and Clark explored the Pacific Northwest in

1805 they found condors there. Until the 1930s, they occurred

in the mountains of Baja California.

- One reason California Condor recovery has been slow is their

extremely slow reproduction rate. Female condors lay only one

egg per nesting attempt, and they don’t always nest every

year. The young depend on their parents for more than 12 months,

and take 6-8 years to reach maturity.

- Condors soar slowly and stably. They average about 30 mph

in flight and can get up to over 40 mph. They take about 16 seconds

to complete a circle in soaring flight. By comparison, Bald Eagles

and Golden Eagles normally circle in 12–14 seconds, and Red-tailed

Hawks circle in about 8–10 seconds.

- At carcasses, California Condors dominate other scavengers.

The exception is when a Golden Eagle is present. Although the

condor weighs about twice as much as an eagle, the superior talons

of the eagle command respect.

- Condors can survive 1–2 weeks without eating. When they

find a carcass they eat their fill, storing up to 3 pounds of

meat in their crop (a part of the esophagus) before they leave.

- California Condors once foraged on offshore islands, visiting

mammal and seabird colonies to eat carrion, eggs and possibly

live prey such as nestlings.

- In cold weather, condors raise their neck feathers to keep

warm. In hot weather, condors (and other vultures) urinate onto

a leg. As the waste evaporates, it cools off blood circulating

in the leg, lowering the whole body temperature. Condors bathe

frequently and this helps avoid buildup of wastes on the legs.

- Adult condors sometimes temporarily restrain an overenthusiastic

nestling by placing a foot on its neck and clamping it to the

floor. This forceful approach is also a common way for an adult

to remove a nestling’s bill from its throat at the end of

a feeding.

- Young may take months to perfect flight and landings. “Crash”

landings have been observed in young four months after their first

flight.

- California Condors can probably live to be 60 or more years

old—although none of the condors now alive are older than

40 yet.

|

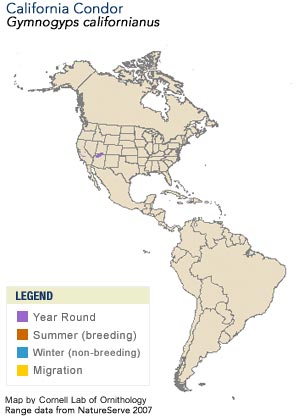

California Condors have been reintroduced to mountains of

southern and central California, Arizona, Utah, and Baja California.

Nesting habitats range from scrubby chaparral to forested mountain

regions up to about 6,000 feet elevation. Foraging areas are

in open grasslands and can be far from primary nesting sites,

requiring substantial daily commutes. Condors glide and soar

when foraging, so they depend on reliable air movements and

terrain that enables extended soaring flight. They are so heavy

that they can have trouble taking off, so they often use open,

windy areas where they can run downhill or launch themselves

from a cliff edge or exposed branch to get airborne. Before

captive breeding programs began in the 1980s all remaining condors

foraged in an area encompassing about 2,700 square miles; this

range is now expanding as the wild population grows. Young condors

learn the full extent of their range partly from other more

experienced birds. |

|

California Condors eat carrion of land and marine mammals

such as deer, cattle, pigs, rabbits, sea lions, and whales.

They swallow bone chips and marine shells to meet their calcium

needs. They favor small to medium-sized carcasses, probably

because smaller bones are easily consumed and digested. Condors

locate carcasses with their keen eyesight (not by smell) by

observing other scavengers assembled at a carcass. Once they

land they take over the carcass from smaller species, but they

are tolerant of each other and usually feed in groups. Condors

are wary of humans while feeding, which is probably why they

do not use roadkill as a food source. In captivity, condors

consume 5–7 percent of their body mass per day to maintain

their weight, but because their crop (an enlarged part of the

esophagus) can hold 3 pounds of food, they may only have to

eat every 2–3 days. Young are fed by regurgitation. |

|

Nesting Facts

Clutch Size

1 eggs

Number of Broods

1 broods

Egg Length

3.6–4.7

in

9.2–12

cm

Egg Width

2.4–2.7

in

6.2–6.8

cm

Incubation Period

53–60

days

Nestling Period

163–180

days

Egg Description

Pale blue-green

bleaching to white

or creamy.

Condition at Hatching

Helpless,

covered in white down

with eyes open.

|

Nesting

Condors lay their eggs directly on the dirt floor of a cliff

ledge or cave, or they construct loose piles of debris from whatever

is available at the nest site, such as gravel, leaves, bark, and

bones. Nests have loosely defined boundaries and are usually about

3 feet across and up to 8 inches deep.

Condors nest mainly in natural cavities or caves in cliffs,

though

they sometimes also use trees, such as coast redwood and, historically,

the giant sequoia. (As the wild population grows, there is the

possibility they may return to the sequoia groves in the Sierra

Nevada.) Condors have multiple nesting sites and may switch

sites between years. Females make the final decision on which

nest location to use. |

|

California Condors can cover hundreds of miles in one flight

as they soar for hours at a time, looking for carrion. These

long-distance travelers pair off during the breeding season

but are highly social at roosting, bathing, and feeding sites;

individuals recognize one another. Generally, condors are not

aggressive towards each other, though dominant birds will threaten

opponents by standing erect, inflating air sacs in the head

and neck, opening the bill and eventually lunging toward the

opponent. Pairs are monogamous. They share nesting duties nearly

equally, stay together throughout the year, and usually endure

until one member dies. Courtship involves coordinated pair flights,

mutual preening, and displays. Young are dependent on their

parents for at least 6 months after fledging; consequently most

condors do not nest in successive years. Condors bathe frequently;

mates and chicks help groom each other’s feathers and skin.

They clean up after feeding by rubbing the head and neck on

a nearby rock or other surface. Condors sun themselves, which

helps dry feathers prior to flight and helps the bird warm up.

Condors roost together on horizontal limbs of tall trees, on

ledges, or in cliff potholes. Sleeping condors sometimes lie

prone on their perch with their heads tucked behind their shoulder

blades. Given their size, condors are not normally hunted by

other animals, except humans and occasionally Golden Eagles;

however, nestlings and eggs are at risk of predation from Common

Ravens, Golden Eagles, and black bears. Young condors play,

especially as late-stage nestlings, mock-capturing all sorts

of objects and vegetation, and leaping about in seeming exuberance. |

|

Conservation

status via IUCN

|

|

|

|

Critically Endangered

|

California Condors are critically endangered. All of the

more than 400 condors now alive are descended from 27 birds

that were brought into captivity in 1987, in a controversial

but successful captive breeding program. As of 2013, there were

more than 230 individuals in the wild in California, Arizona,

and Baja California. The number has been rising steadily each

year, as captive-bred birds are released and wild pairs fledge

young from their own nests. More than 160 additional condors

live in captivity at breeding programs at The Peregrine Fund,

Los Angeles Zoo, and San Diego Zoo. Condors have benefited greatly

from the Endangered Species Act and from aggressive efforts

to breed them in captivity and re-release them into the wild,

but the survival of the species is still dependent on human

intervention. The major threat is lead poisoning, caused by

ammunition fragments in carcasses they eat. Historically, reasons

for their decline also included accidental poisoning from lead

and from strychnine-laced carcasses left out for coyote control

programs. Hunting by humans also had a substantial effect on

condor populations. Condor recovery has been slow because of

their slow reproductive rate: they produce only 1 egg every

1–2 years and do not achieve sexual maturity until age

6-8 years. Wild birds are still supplied with clean (lead-free)

carcasses, but they also feed on their own, sometimes on lead-contaminated

carcasses that can result in their deaths. To alleviate the

lead-poisoning problem, workers catch each condor twice per

year to test their blood lead levels; birds that test high are

treated to remove the lead through a technique called chelation.

In 2010 the Peregrine Fund reported that 72 percent of condors

tested in the Vermilion Cliffs, Arizona, showed lead in the

blood, and 34 condors had to be treated. The only route to self-sustaining

wild populations will be by solving the lead-poisoning problem.

Promising first steps have been taken, including a 2008 ban

on lead ammunition used for hunting in the condor’s California

range, and an innovative voluntary program in Arizona. |

|

The

spectacular but endangered California Condor is the largest bird

in North America. These superb gliders travel widely to feed on

carcasses of deer, pigs, cattle, sea lions, whales, and other animals.

Pairs nest in caves high on cliff faces. The population fell to

just 22 birds in the 1980s, but there are now some 230 free-flying

birds in California, Arizona, and Baja California with another 160

in captivity. Lead poisoning remains a severe threat to their long-term

prospects.

The

spectacular but endangered California Condor is the largest bird

in North America. These superb gliders travel widely to feed on

carcasses of deer, pigs, cattle, sea lions, whales, and other animals.

Pairs nest in caves high on cliff faces. The population fell to

just 22 birds in the 1980s, but there are now some 230 free-flying

birds in California, Arizona, and Baja California with another 160

in captivity. Lead poisoning remains a severe threat to their long-term

prospects.