|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

April 2014 - Volume

12 Number 4

|

||

|

|

||

|

Kachina Carver Overcomes

Obstacles, Passes On Tradition To Son

|

||

|

by Katherine Locke -

Reporter, Navajo-Hopi Observer

|

||

|

Honyumptewa lived in Moenkopi until he was about 17 years old. He attended the Indian school in Phoenix for four years - nine months out of the year. He came home after school to look for a job but when he could not find one he left for New Mexico. "It was hard to find jobs in the isolated mountain communities," he said As a child he learned how to weave wedding sashes. He made his living by trading and selling his weavings to people until he started carving regularly. "I alternated between weaving and carving," Honyumptewa said. But he was carving mostly on the side while looking for other jobs that would pay his bills and help him to survive. He decided that he needed to find a gallery that would help him sell his carvings and ended up in a gallery called Broken Arrow where he honed his craft. "As time went on I got better," he said. Eventually, another gallery, Blue Rain gallery, paid top dollar for his kachina carvings. He said that he gives credit to Steve Cowgill who helped him get his work known. He won five best in class awards within seven years for his carvings, one right after another. "From then on, everything just snowballed," Honyumptewa said.

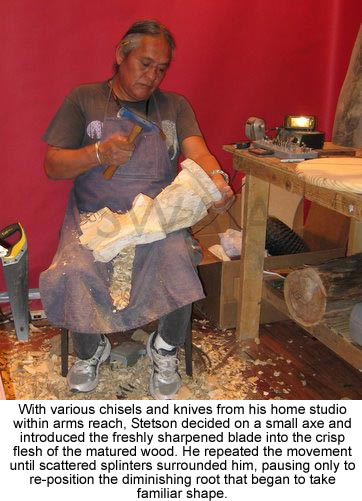

He said his inspiration for carving springs from the Hopi culture. Each carving takes Honyumptewa about three months to make. The time it takes is always dependent on the size of the doll and the detail involved. He makes the dolls out of cottonwood root, which he explained is a traditional medium. "The cottonwood tree is where moisture is in the desert and that is what we strive for at Hopi because it is really dry and we always want rain," Honyumptewa said. "The trees can find water anywhere and we use that to help us make dolls so we can ask for rain." He explained that most of the time he sees something in the wood that shows him what kind of doll he will carve, but sometimes he brainstorms about the carving instead. Honyumptewa said becoming a successful carver has not always been easy. "I used to make the dolls and get paid and the first thing I would do is go drinking until the money was gone," he said, an experience he said is common. "It took me half of my life to realize what I was doing to myself and so I stopped drinking and I am in my ninth year of sobriety." Honyumptewa said anyone can change as long as they remember who they are and where they come from. "You have to look at your background and your culture. That is what they are all teaching us. You can change yourself. It is all up to the individual," he said. "I tried to be the best Hopi I could. I am trying to be Hopi." A New Generation Aaron said his father was influential in his decision to become a carver. He was able to sell some of his carving at a young age at the galleries his father sold to, which was a lucky break. "They were interested because we were his sons, me and my brother, it started me off," Aaron said. Despite his father's encouragement, he went for many years, through high school, without carving because when he had to add details onto his carvings, instead of carving flat dolls, he got nervous and put them aside. "Because it was a piece of wood that he gave me, I felt like it was money, it was not just a piece of wood and I was scared to finish it," Aaron said. He said his father finished that piece for him and he put carving aside. Aaron said his teachers at school were not very encouraging. "They said, 'artists are starving, why do you want to be an artist?'" he said. But carving was not his only creative outlet. He was an illustrator. He made drawings and paintings. He was a musician, too. He said having his first daughter inspired him to pick up carving again. He created a doll that was a side view like the carving had been cut in half.

He told his wife that he was going to stop working and that he would spend the next year trying to make a living as an artist. "I told her that if we can't make it through that year, then I will go back to working," Aaron said. "But I made it through." Aaron does not just make dolls. He also does silkscreen work. He illustrates t-shirts, paints and is a graphic designer. He said that he tried to do anything that was artistic. "I am addicted to the lifestyle," Aaron said. "I don't want to go back to making money for someone else." He uses cottonwood root like his father and said that everything he does he has learned from his father. "He gave me everything that he has, including his tools," Aaron said. "I feel like the ability is still in his tools, it's like touching it when you're able to use those things." Aaron said he gets the inspiration for what to carve from a vision in his head and then he looks for the right piece of wood to see if there is enough space for the vision. When he illustrates he does not sketch out an image first, he just draws from scratch without any fear and he does the same thing with carving. "That's the ability I really wanted to harness," Aaron said. "When I went to carving, if I made a mistake, I had to manipulate it and get it to where it works." Carving, like everything, involves improving over time. He said that learning is never done. Aaron said both he and his father can see the mistakes in the carvings they make, but that the only person they compete with is themselves. "My father said, 'you don't want to say anything about anyone else's work because that's their heart,'" Aaron said. "Each individual is their own competition." For Aaron, art is everywhere, in everything he sees. "Everything to me is inspiration," Aaron said. "That's what they are, the Katsinas, the bringers of life." |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2014 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2014 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

PHOENIX,

AZ - Stetson Honyumptewa overcame difficulties with alcohol and

a lack of career opportunities both in Arizona and New Mexico to

become the signature artist at the 56th annual Heard Museum Guild

Indian Fair and Market March 1-2, 2014.

PHOENIX,

AZ - Stetson Honyumptewa overcame difficulties with alcohol and

a lack of career opportunities both in Arizona and New Mexico to

become the signature artist at the 56th annual Heard Museum Guild

Indian Fair and Market March 1-2, 2014. Two

years ago, Honyumptewa entered the Heard Museum Indian Fair and

the piece he brought with him won best of show. That's how he became

the signature artist this year.

Two

years ago, Honyumptewa entered the Heard Museum Indian Fair and

the piece he brought with him won best of show. That's how he became

the signature artist this year. "My

dad saw that and said 'wow, that is really good, see you have got

some talent there, just push it.' That was the first encouraging

thing," Aaron said. "After that first sale, I said, 'hey I can actually

do this.' All my life all I really ever wanted to do was be an artist."

"My

dad saw that and said 'wow, that is really good, see you have got

some talent there, just push it.' That was the first encouraging

thing," Aaron said. "After that first sale, I said, 'hey I can actually

do this.' All my life all I really ever wanted to do was be an artist."