|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

January 2014 - Volume

12 Number 1

|

||

|

|

||

|

Indian Family Sees

Its History in a Shirt

|

||

|

by Leslie Macmillan

- The New York Times

|

||

|

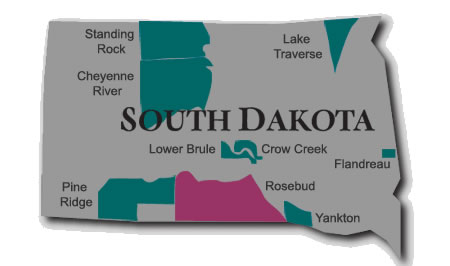

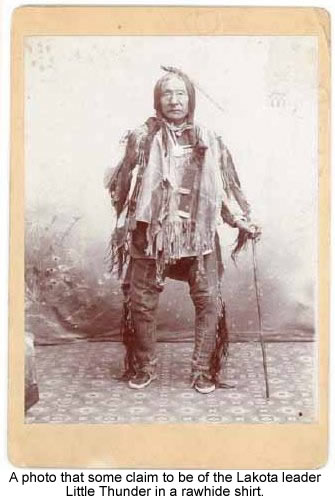

"He was a great leader who always had the greasiest tepee door, because he was generous and was always feeding people," she said. Little Thunder, described by one trader as "six feet or more in height, handsome, with a commanding bearing and superior intelligence," led a band of Sicangu Lakota that lived along the Platte River, which runs east to west across what is now central Nebraska. He rose to prominence in 1854, after United States Army soldiers shot his predecessor Conquering Bear over a dispute involving a "ten-dollar cow that had wandered into a Lakota encampment from a Mormon wagon train," said Peter Gibbs, a retired curator of the Native American art collection of the British Museum, who has done research on the Lakota and has taught at a university on the reservation. In a photograph of a man the family believes to be Little Thunder, taken around 1860, he poses in an elaborate rawhide shirt. On the sleeves are locks of hair given to him by his people or perhaps cut from scalps taken in battle, as well as eagle feathers dyed red and white to symbolize the civil and war responsibilities of his office. Last fall, a history professor on the reservation contacted the family after noticing, in an auction catalog, a shirt that looked like the one in the photo. The Skinner auction house in Boston had listed it as a "Sioux Beaded and Quilled Hide Shirt" and estimated it would fetch between $150,000 and $300,000 at its Nov. 9 sale. But minutes before the bidding began, Skinner withdrew the item from the auction in response to pressure from lawyers and tribal officials representing the Little Thunder family. Karen Little Thunder is the main family member pressing the suit. "This is not just a pretty object that you go and sell," said Mr. Gibbs, who said the shirt has historical significance because of its former owner. Cultural property claims can be complex: The competing interests of good-faith collectors and plundered civilizations have to be adjudicated among complications like the passage of time, the disappearance of records and the evolution of law. Douglas Diehl, director of the American Indian and ethnographic art department at the auction house, would not discuss the matter when reached by phone, but released a statement saying that Skinner "is committed to the highest standards of research and due diligence" and is "particularly sensitive to Native American artifacts." The collector who consigned the item for sale, Charles E. Derby, said that he had good title to the shirt. He bought it, according to his lawyer, William H. Fry, from another collector in the early 1980s and has a bill of sale. Mr. Fry said his client could track the shirt, which has been shown in museums, back to 1955, when it was displayed, and later sold, by a bookstore in Cambridge, Mass. A lawyer for the Little Thunder family, Robert P. Gough, said that a collector would need a lengthier provenance for the shirt to claim good title. Mr. Gough is relying on a series of laws that restricted the buying and selling of land and personal property between Indians and white people. Some of these laws, which protected Indians from desperately selling their property for unfair prices, were in force until 1953, only two years before the shirt was purchased from the bookstore. A transfer, even a sale, of the shirt to a white person that took place before 1953 would have been prohibited by law, Mr. Gough contends, leaving only a two-year window for the shirt to have left the tribe. Mr. Gough says that no one in the family can remember such a transaction then. But Mr. Fry, the seller's lawyer, took issue with that reading of the Indian commerce laws. He said that the laws promoted an outdated and "paternalistic view" of Native Americans and that the last of them were repealed in 1953, at the request of Native Americans. "The law made it illegal for them to buy, sell and possess personal property — it treated them as wards of the state who were incapable of making their own decisions," he said. "There's no doubt it's the old man's shirt," Mr. Gibbs said. If the family cannot negotiate the return of the shirt, Mr. Gough said the family would ask for help from the United States Department of the Interior, which has jurisdiction over cultural property issues for Native Americans. As tensions escalated on the Great Plains in the mid-19th century, Little Thunder played a significant role in ensuing Indian wars. He was a Lakota leader in 1855 when the United States Army marched into his village at the Blue Water Creek, near Ash Hollow, in southwest Nebraska. The Army was on a retaliatory mission: The year before, 29 soldiers had died in a battle with the Lakota. Historians say that Little Thunder tried to surrender but was rebuffed. According to Army records, 86 Lakota were killed that day, and 70 women and children taken prisoner. Little Thunder was wounded. As the battle raged, a teenager named Crazy Horse rode into camp, and the carnage he witnessed made an indelible impression. Twenty years later, he helped lead the Lakota and their allies to wipe out the Seventh Cavalry at the Little Bighorn in 1876. By then, Little Thunder was already living on the Rosebud reservation, where he died three years later. In his lifetime, he had seen the Great Sioux Nation — which once stretched from the Bighorn Mountains in Montana to eastern Wisconsin, and from the border of Canada to the Platte River in Nebraska — shrink to three reservations. For the Little Thunder family, that history still lives. Karen Little Thunder, 48, said the shirt represents greatness that is within reach — only a few generations back. "It gives us," she said, "something to hold on to." |

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2013 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2013 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Ten

years ago, lost to drugs and alcohol, Karen Little Thunder moved

back to the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where, she

said, she saved her own life by reconnecting to her Lakota heritage,

particularly the legacy of her great-great grandfather. He was Little

Thunder, a Lakota leader and a contemporary of Crazy Horse, whose

life spanned several decades central to the history of the tribe

— from the battles it fought across the Great Plains to its

resettlement on reservations.

Ten

years ago, lost to drugs and alcohol, Karen Little Thunder moved

back to the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where, she

said, she saved her own life by reconnecting to her Lakota heritage,

particularly the legacy of her great-great grandfather. He was Little

Thunder, a Lakota leader and a contemporary of Crazy Horse, whose

life spanned several decades central to the history of the tribe

— from the battles it fought across the Great Plains to its

resettlement on reservations. Since

there are no known photographs of Little Thunder, Mr. Fry questioned

how the family could even be sure the man in the photo was an ancestor.

Since

there are no known photographs of Little Thunder, Mr. Fry questioned

how the family could even be sure the man in the photo was an ancestor.