Moonchildren

settle back. Remember the cold. Remember the dark nights and

short days of time before time and when the Earth is at rest.

Sit closely together in the long nights of time and recall the

stories told and retold. Moonchildren

settle back. Remember the cold. Remember the dark nights and

short days of time before time and when the Earth is at rest.

Sit closely together in the long nights of time and recall the

stories told and retold.

Winter stories from many tribes

on this Indian land. Our voices sustain us as we spin in the

universe as the seeds spin in gourd rattles. Stand closely

together, link arms and dance. Dance in our orbits of life

and tradition.

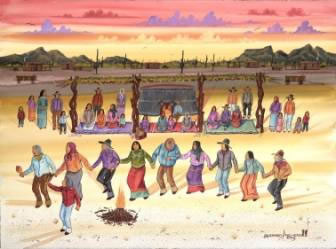

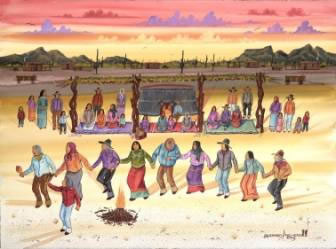

Circles of life are the round dance

in form and in respect the example of our celestial relations.

We are all made of star stuff. Dance our brother sun back

from these short days and cold nights. Our songs are a prayer

and the dance a testament to our spirituality. Dance, dance,

dance and let the stories fill your heart.

At the Winter Solstice, we honor

our children and dance to bring warmth, light and cheerfulness

into the dark time of the year. Winter Holidays such as these

have their origin as special days. They are the way human

beings have marked the sacred times in the yearly cycle of

life.

The

winter solstice is the moment when the earth is at a point

in its orbit where one hemisphere is most inclined away from

the sun. This causes the sun to appear at its farthest below

the celestial equator when viewed from earth. The

winter solstice is the moment when the earth is at a point

in its orbit where one hemisphere is most inclined away from

the sun. This causes the sun to appear at its farthest below

the celestial equator when viewed from earth.

Solstice is a Latin borrowing and

means “sun stand”, referring to the appearance that

the sun’s noontime elevation change stops its progress,

either northerly or southerly. The day of the winter solstice

is the shortest day and the longest night of the year.

The sun image at left is from rock

paintings of the Chumash, who occupied coastal California

for thousands of years before the Europeans arrived. Solstices

were tremendously important to them, and the winter solstice

celebration lasted several days.

Another winter dance is the Bear

Dance symbolizes putting the Great Bear to sleep for his winter

hibernation. First, the Bear appears (as a ghost) and walks

the area of the dance to clear it of all bad spirits that

may be present. When Bear is done clearing the area, the living

Indians start a log fire and begin the Bear Dance with song

or chant. As they dance, their ancestors join the dance in

spirit form. Slowly the Bear is lulled to sleep for the winter

and the dance is complete.

Another dance that usually follows

the Bear Dance is the Round Circle (or Cycle) of Life dance.

This dance begins with a log fire symbolizing the light and

warmth of the sun and continues until the light fades or dawn.

Before the Maya of Central America

built their arrow-straight roadways, the creative Hopewell

culture flourished in North America’s Midwest to rise

up monuments of earth that rivaled England’s Stonehenge

in their astronomical accuracy.

In the area that comprises Ohio,

Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois, the Adena, Hopewell and Fort

Ancient peoples erected hundreds of astronomical circles,

octagons, rectangles (and later animal effigies) stretching

thousands of feet in length and reaching 15 feet in height.

The works served as incredibly precise in plotting and marking

the moon’s subtle rhythms.

The remarkable technical capacity

and culture of the Adena (who built cones and rings starting

from 600 BC), the Hopewell (who specialized in geometric enclosures

from 100 BC to AD 400), and later the Fort Ancient (building

animal shapes from 700-1200 AD) peoples are, at best, overlooked

even within the region where they concentrated their efforts,

erecting earthworks of astonishing size and precision.

Cherokee: In the beginning, there

was only darkness and people kept bumping into each other.

Fox said that people on the other side of the world had plenty

of light but were too greedy to share it. Possum went over

there to steal a little piece of the light. He found the Sun

hanging in a tree, lighting everything up. He took a tiny

piece of the Sun and hid it in the fur of his tail. The heat

burned the fur off his tail. That is why possums have bald

tails.

Buzzard tried next. He tried to

hide a piece of Sun in the feathers of his head. That is why

buzzards have baldheads.

Grandmother Spider tried next. She

made a clay bowl. Then she spun a web (Milky Way) across the

sky reaching to the other side of the world. She snatched

up the whole sun in the clay bowl and took it back home to

our side of the world.

Zuni story: Back when it was always

dark, it was also always summer. Coyote and Eagle went hunting.

Coyote was a poor hunter because of the dark. They came to

the Kachinas, a powerful people. The Kachinas had the Sun

and the Moon in a box.

After the people had gone to sleep,

the two animals stole the box.

At first Eagle carried the box but

Coyote convinced his friend to let him carry it. The curious

Coyote opened the box and the Sun and Moon escaped and flew

up to the sky. This gave light to the land but it also took

away much of the heat, thus we now have winter.

Navajo Indians of North America,

Tsohanoai is the Sun god. Everyday, he crosses the sky, carrying

the Sun on his back. At night, the Sun rests by hanging on

a peg in his house.

Tsohanoai’s two children Nayenezgani

(Killer of Enemies) and Tobadzistsini (Child of Water) were

separated from their father and lived with their mother in

the far West. Once they were older, they tried to find their

father, hoping he could help them fight the evil spirits tormenting

mankind.

They met Spider Woman, who gave

them two feathers to keep them safe on their journey.

Finally, they found Tsohanoai’s

house, and he gave them magic arrows to fight off the evil

monsters, Anaye.

Northwest Coast: Tells us of the

time when the sky had no day. When the sky was clear there

was some light from the stars but when it was cloudy, it was

very dark.

Raven had put fish in the rivers

and fruit trees in the land but he was saddened by the darkness.

A chief in the sky kept the Sun

at that time in a box.

The Raven came to a hole in the

sky and went through. He came to a spring where the chief’s

daughter would fetch water. He changed himself into a cedar

seed and floated on the water.

When the girl drank from spring,

she swallowed the seed without noticing and became pregnant.

A boy child was born which was raven.

As a toddler, he begged to play with the yellow ball, that

grandfather kept in a box. He was allowed to play with the

Sun and when the chief looked away, he turned back into Raven

and flew back through the hole in the sky.

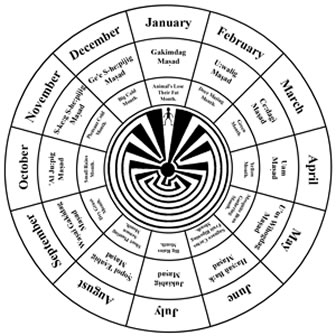

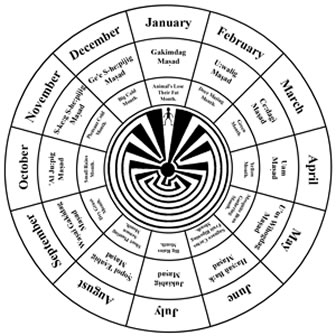

The Tohono O’odham name for

December - “moon of the backbone.” This is because

the days are half dark and half light. Seems fitting for the

month of the winter solstice. Ofelia Zepeda tells of traveling

to Waw Giwulig, the most sacred mountain of the Tohono O’odham,

to ask for blessings-and forgiveness. She writes that one

should always bring music to the mountains, “so they

are generous with the summer rains.” And, still, “the

scent of burning wood / holds the strongest memory. / Mesquite,

cedar, piñon, juniper, . . . / we catch the scent of

burning wood; / we are brought home.” It is a joy to

see the world afresh through her eyes.

The

earlier Hohokam were concerned about their place in the universe

and, therefore, the observations and solstice/equinox markings

served to initiate and confirm ceremonial cycles important

to the Hohokam. Near Phoenix, Arizona the Shaw butte site

has indications that that Certain group rituals may have been

performed in the cleared areas inside the compound before,

during or after special solar or lunar events, as determined

by a sacred calendar maintained by Hohokam priests. For rest

of the year, an individual sun watcher may have been responsible

for maintaining the site and making observations. The Tohono

O’odham (Papago) Indians assigned sun and star watching

to a single individual, who reported his observations to the

village chief. Those observations established a seasonal ritual

calendar. The

earlier Hohokam were concerned about their place in the universe

and, therefore, the observations and solstice/equinox markings

served to initiate and confirm ceremonial cycles important

to the Hohokam. Near Phoenix, Arizona the Shaw butte site

has indications that that Certain group rituals may have been

performed in the cleared areas inside the compound before,

during or after special solar or lunar events, as determined

by a sacred calendar maintained by Hohokam priests. For rest

of the year, an individual sun watcher may have been responsible

for maintaining the site and making observations. The Tohono

O’odham (Papago) Indians assigned sun and star watching

to a single individual, who reported his observations to the

village chief. Those observations established a seasonal ritual

calendar.

The Hopi sun priests make use of

thirteen points on the horizon for the determination of ceremonial

dates. Their ritual year begins in November with a New Fire

ceremony, which is given in an elaborate and extended from

every fourth year, for it then includes the initiation of

novices into the fraternities. Other ceremonies are similarly

elaborated at these same times; while still other rites, as

the Snake- and Flute Dances, occur in alternate years. The

Hopi year is divided into two unequal seasons, the greater

festivals occurring in the longer season, which includes the

cold months. Five and nine days are the usual active periods

for the greater festivals, though the total duration from

the announcement to the final purification is in some instances

twenty days. Of the greater festivals, the Soyaluna follows

the New Fire ceremony of November at the winter solstice.

This

is which the germ god is supplicated and the return of the

sun, in the form of a bird, is dramatized; the Powamu, or

Bean-Planting. This time comes in February. The main object

being the renovation of the earth for the coming sowing and

the celebration of the return of the Kachinas, to be with

the people until their departure at Niman. Following the home

dance, summer solstice; the Snake Dance alternates with the

Flute-Dance in the month of August. Theseare only a few of

the annual festivals, a striking feature of which is the arrival

and departure of the Kachinas. The period during which these

beings remain among the Hopi is approximately from the winter

to the summer solstice. Also, found only in Kachina ceremonies,

is the presence of clowns or “Mudheads”–a curious

type of fun-maker whose presence in Zuni Cushing ascribes

to the ancient union of a Yuman tribe with the original Zunian

stock. This

is which the germ god is supplicated and the return of the

sun, in the form of a bird, is dramatized; the Powamu, or

Bean-Planting. This time comes in February. The main object

being the renovation of the earth for the coming sowing and

the celebration of the return of the Kachinas, to be with

the people until their departure at Niman. Following the home

dance, summer solstice; the Snake Dance alternates with the

Flute-Dance in the month of August. Theseare only a few of

the annual festivals, a striking feature of which is the arrival

and departure of the Kachinas. The period during which these

beings remain among the Hopi is approximately from the winter

to the summer solstice. Also, found only in Kachina ceremonies,

is the presence of clowns or “Mudheads”–a curious

type of fun-maker whose presence in Zuni Cushing ascribes

to the ancient union of a Yuman tribe with the original Zunian

stock.

Spinning rattles in the night. Songs

calling the people to smile, cry, love and live in the life

our elders told and retold us. Rattles spin in time and call

to our relations of the past and celestial to shine.

|

Moonchildren

settle back. Remember the cold. Remember the dark nights and

short days of time before time and when the Earth is at rest.

Sit closely together in the long nights of time and recall the

stories told and retold.

Moonchildren

settle back. Remember the cold. Remember the dark nights and

short days of time before time and when the Earth is at rest.

Sit closely together in the long nights of time and recall the

stories told and retold.

The

winter solstice is the moment when the earth is at a point

in its orbit where one hemisphere is most inclined away from

the sun. This causes the sun to appear at its farthest below

the celestial equator when viewed from earth.

The

winter solstice is the moment when the earth is at a point

in its orbit where one hemisphere is most inclined away from

the sun. This causes the sun to appear at its farthest below

the celestial equator when viewed from earth. The

earlier Hohokam were concerned about their place in the universe

and, therefore, the observations and solstice/equinox markings

served to initiate and confirm ceremonial cycles important

to the Hohokam. Near Phoenix, Arizona the Shaw butte site

has indications that that Certain group rituals may have been

performed in the cleared areas inside the compound before,

during or after special solar or lunar events, as determined

by a sacred calendar maintained by Hohokam priests. For rest

of the year, an individual sun watcher may have been responsible

for maintaining the site and making observations. The Tohono

O’odham (Papago) Indians assigned sun and star watching

to a single individual, who reported his observations to the

village chief. Those observations established a seasonal ritual

calendar.

The

earlier Hohokam were concerned about their place in the universe

and, therefore, the observations and solstice/equinox markings

served to initiate and confirm ceremonial cycles important

to the Hohokam. Near Phoenix, Arizona the Shaw butte site

has indications that that Certain group rituals may have been

performed in the cleared areas inside the compound before,

during or after special solar or lunar events, as determined

by a sacred calendar maintained by Hohokam priests. For rest

of the year, an individual sun watcher may have been responsible

for maintaining the site and making observations. The Tohono

O’odham (Papago) Indians assigned sun and star watching

to a single individual, who reported his observations to the

village chief. Those observations established a seasonal ritual

calendar. This

is which the germ god is supplicated and the return of the

sun, in the form of a bird, is dramatized; the Powamu, or

Bean-Planting. This time comes in February. The main object

being the renovation of the earth for the coming sowing and

the celebration of the return of the Kachinas, to be with

the people until their departure at Niman. Following the home

dance, summer solstice; the Snake Dance alternates with the

Flute-Dance in the month of August. Theseare only a few of

the annual festivals, a striking feature of which is the arrival

and departure of the Kachinas. The period during which these

beings remain among the Hopi is approximately from the winter

to the summer solstice. Also, found only in Kachina ceremonies,

is the presence of clowns or “Mudheads”–a curious

type of fun-maker whose presence in Zuni Cushing ascribes

to the ancient union of a Yuman tribe with the original Zunian

stock.

This

is which the germ god is supplicated and the return of the

sun, in the form of a bird, is dramatized; the Powamu, or

Bean-Planting. This time comes in February. The main object

being the renovation of the earth for the coming sowing and

the celebration of the return of the Kachinas, to be with

the people until their departure at Niman. Following the home

dance, summer solstice; the Snake Dance alternates with the

Flute-Dance in the month of August. Theseare only a few of

the annual festivals, a striking feature of which is the arrival

and departure of the Kachinas. The period during which these

beings remain among the Hopi is approximately from the winter

to the summer solstice. Also, found only in Kachina ceremonies,

is the presence of clowns or “Mudheads”–a curious

type of fun-maker whose presence in Zuni Cushing ascribes

to the ancient union of a Yuman tribe with the original Zunian

stock.