|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 2013 - Volume

11 Number 12

|

||

|

|

||

|

The Coolest Cowboys

Are From Indian Country At National Rodeo Finals

|

||

|

by Tristan Ahtone -

Al Jazeera America

|

||

|

credits: all photos by

Tomas Muscionico for Al Jazeera America

|

|

At the Indian National Finals Rodeo, Native Americans give lessons on what a 21st century cowboy looks like

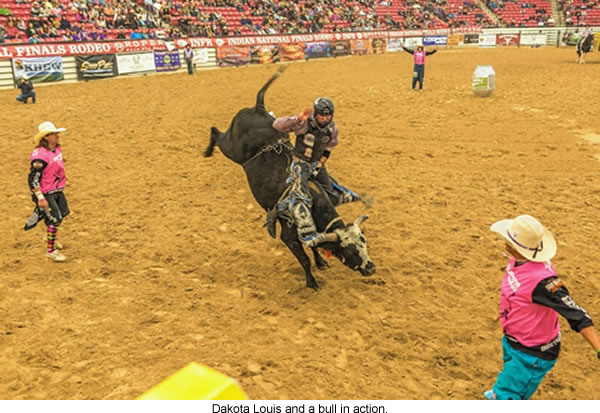

LAS VEGAS — By the final round Saturday night at the Indian National Finals Rodeo, all Dakota Louis needed to do was stay on his bull for 8 seconds and score more than 53 points to win his third world-champion bull-riding title. All the bull had to do was buck hard enough to throw him off before the whistle blew in this, its final rodeo outing before retirement. The two knew each other. Three years ago, Louis was 18 when he first competed in bull riding at the finals, and he was on the same top-ranked bull, a behemoth named Slow Ride. Louis, a Northern Cheyenne tribe member from Montana, won that round. Only one other bull rider has ever garnered three world-champion titles in the history of this rodeo, and Louis' father is a two-time Indian world-champion bull rider. If Louis won, he would surpass his father and enter a whole new class of rider. All he needed was 8 seconds. "Bull riding has been voted the most dangerous sport in the whole world," Louis said earlier in the day. "So I guess they look at us like gladiators." Rodeo is an integral sport to many in Indian Country. And the INFR, the championship competition for tribal members held each year in Las Vegas, is the pinnacle. At its core, the finals are a celebration of the farm and ranch lifestyle in Indian Country as well as a lesson in what a cowboy looks like in the 21st century. Competitors are heirs to the legacy of the indigenous peoples in whose cultures the horse was key. For some tribes, their skill with horses meant they could drive bargains and treaties with white settlers and governments, saving land and lives. In the old game of cowboys and Indians, there was a cultural expectation of who would win. But at the rodeo, Native Americans are out of the shadow of national guilt, malice and confusion. They're still on horseback.

Practically a family reunion Unlike other, non-Native rodeos, this event almost feels like a family reunion. In this crowd, families compete together, and the extended family grows each year, with contestants swapping and borrowing equipment and even livestock, exchanging tricks, tips and services and finding ways to support one another from rodeo to rodeo across the United States. For instance, this year the Louis family competitors included Dakota's father wrestling steer, Dakota's little brother also riding bulls and their sister barrel-racing in the junior division. "When you go to a non-Indian rodeo or sport, it's like the professional basketball players. You go there as your own. They're not brothers," said Freddy Heathershaw, a former INFR judge. "It's just way different." The notion that Indians make better cowboys because of their long history with horses is prevalent among the competitors, judges and spectators at INFR. For the last 38 years, Native Americans competing at INFR have ridden bulls and broncos, roped calves and barrel-raced. Not much has changed in the years since the competition began or even since people began climbing atop bulls to see how long they could stay on. "These guys, maybe they got some professional training, but when they get on a horse and that gate opens, they're no different than it was 20 years ago," said Heathershaw. "They might have better equipment and stuff like that, but you still gotta have the balls to do it." A working man's sport The difference between the INFR and other highly competitive national rodeos is ultimately racial identity. To be considered Indian, competitors must be enrolled members of a federal recognized tribe. Competitors come dressed in their cowboy and cowgirl best — pearl-button-snap shirts, perfectly fitted cowboy hats, worn boots and tight-fitting jeans. Nearly all participants are in excellent shape, many working out daily. Contenders aren't required to wear protective gear, so many don't. Those who do often adopt items like leather vests to provide some protection for internal organs should they be kicked by a horse, and a few don helmets to guard against the kind of life-threatening injuries that a 1-ton bull can inflict when angry. Younger riders are beginning to adopt life-saving gear in greater numbers. "They're wearing helmets, they're wearing protective vests, and a lot of that is just becoming more natural to everybody," said Steve Williamson, an arena physician with the INFR. "What they're learning is if they're not healthy, there's no chance for them to get a paycheck." Rodeo is a working man's sport. While players injured in the NFL go on the injured list and continue to collect salaries, rodeo competitors that don't play don't get paid.

Risk, rush, reward While injuries occur in rodeo, there has been only one death at the INFR. Last year, on the final night of the championship, bronc rider J.D. Jones and the horse he rode both died. Jones tried to dismount the horse after completing his run but caught his leg in the stirrup. At the same time, the horse jumped and fell. Jones was kicked in the head, and the horse broke its hip. "They know when they get on that horse or when they get on that bull that they might not be coming back to their family," said Williamson. "So that's why they give their spouse a hug and a kiss, they hug their kids one more time before they get on the animal, because that might be the last time that they see them." It's this risk and rush that attract many rodeo adherents. The cash prizes don't hurt either. In bull riding alone, cash prizes at the INFR run roughly $2,000 per night, plus a best overall score cash prize of about $4,000. The only way to make rodeo a full-time job is to keep competing and winning. Equipment isn't cheap. "For a kid to start out — let's say in the saddle bronc riding — you probably need about $2,000 to buy the equipment you need," said Todd Buffalo, an INFR judge. "Bronc saddle is going to cost you over a thousand dollars. Chaps nowadays are four or five hundred dollars. Boots are two, three hundred dollars. Spurs are going to cost you a hundred dollars." Because almost everyone involved in rodeo comes from a family involved in farming or ranching, many rodeo officials, like Buffalo, are worried about the sport's future. With taxes, a volatile marketplace and shrinking land bases, ranching is a tough life and one that seems to be slowly disappearing in the United States, regardless of ethnicity. "The first time I entered Crow Fair in the bronc riding, they had 90 bareback riders, they had 120 saddle bronc riders, and they had 160 bull riders," said Buffalo. "Nowadays we might have 20 bull riders, we might have 14 bronc riders, we might have six bareback riders."

Slow Ride's last ride In spite of that dispiriting trend, you didn't see that attitude in competitors Saturday night when ropers and riders stepped out to make their final plays for the title of world champion. "He's had this bull before," the announcer bellowed to the crowd as Dakota Louis prepared for the ride that would send him home or crown him world champion for a third time. "It's a good draw," continued the announcer. "He likes him. He knows him. He's a jump at a time. The bull can't read your resume." Baby-faced Louis strode up a platform to his waiting bull. Save for a silver cross on a large silver chain, Louis wore all black: black shirt, black chaps, black vest and black hat, which he traded for a black helmet. Clang! As soon as the metal gates were flung open, he was out in the arena on the back of an angry, bucking bull — crowd screaming, announcers shouting, competitors cheering, children hooting and violent death or glory just seconds away. Bloooot! Eight seconds up. "That bull tried to get out from under him," the announcer said. "No way, Jose." "We only needed 53," intoned another announcer, referring to the number of points Louis needed to win. "How about 63? He's the world champion three times!" The crowd erupted. Music blared. The rodeo queens entered the sandy arena on horseback to escort Louis on a victory lap. Audience members got to their feet, hollering even as some of them began to file out. As Louis left the stage, his fiancee pulled him close and kissed him. Repeatedly. Slow Ride left the ring, never to return. And Freddy Heathershaw looked on with pride. "Cowboys are the coolest, Indian cowboys especially," he said. "They are the coolest (expletive) goin' down the road, man." |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2013 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2013 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||