|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

October 2013 - Volume

11 Number 10

|

||

|

|

||

|

Touring Hopi Via

A 10K Running Race At Dawn

|

||

|

by Jonathan Thompson

- High Country News

|

||

| I run. And I weep. My tears may come from the fact that it’s

6 a.m., or perhaps from the burning in legs and lungs as I try to

hold the pace of the leaders. But I’m pretty sure my sobs come

from a deep joy inspired by the way the rising sun lights up the ancient

buildings of Old Oraibi on a mesa distant, and the way it does so

at the very moment that gravel road gives way to a narrow rain-dampened

trail. This trail, I imagine, has been trod for centuries by runners

vying against one another, or heading off to distant farms to tend

to the corn. My 97 fellow runners and I, it seems, have transcended

time.

It’s early September, and this is the 40th annual Louis Tewanima 10 kilometer footrace, which takes place in and around the Hopi village of Shungopavi in northern Arizona. The race is named after a Hopi who was yanked as a young man from his home in Shungopavi in 1907 and shipped off to boarding school in Carlisle, Penn. There, the cross-country coach noticed the youngster’s talent, and Tewanima began running competitively. He finished 9th in the 1908 Olympic Marathon, and won the silver medal in the 1912 Olympic 10,000 meter run, setting an American record that held until Billy Mills, a Sioux, broke it in 1964.

The Hopi culture is as deeply embedded as any in the canyons and mesas of the Southwest. Their ancestors are the Ancestral Puebloans, neé Anasazi, who once inhabited much of the Four Corners Region, and built the pueblos of Chaco Canyon, Mesa Verde and Hovenweep. Over time the Puebloans packed up and moved, as people sometimes do, migrating to other parts of the region, and various branches of their descendants now live in the pueblos along the Rio Grande, Zuni and in the 12 Hopi villages on and around three mesas that extend into the high desert like fingers from Black Mesa in northern Arizona. Here the Hopi endured and then, in a well-coordinated Pueblo uprising in 1680, cast off Spanish colonists. And they’ve continued to successfully keep much of their culture and traditions intact, despite intrusions from the outside. One of those traditions is the art of arid farming. There is no rich, loamy Iowa soil here, or huge sprinkler systems or, for that matter, a ditch. One can find corn growing, seemingly impossibly, in little sandy plots among brush and desert grass. Another tradition that endures is running, which was connected to farming, among other things, writes Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert in his paper, Marathoner Louis Tewanima and the Continuity of Hopi Running:

These days, Hopi farmers probably drive, not run, to their distant fields. But they still run for both ceremonial and competitive purposes. The Hopi High School cross-country team has won every state championship in its division since 1989, and the Tuba City team, with both Navajo and Hopi runners, vies with Chinle for dominance of its division. Several runs are hosted by Hopi villages in late summer, including the Tewanima footrace.

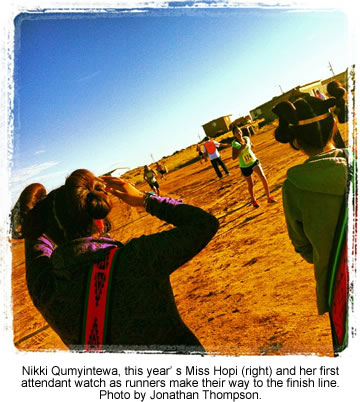

“The Hopi are very welcoming people,” says Sampson Taylor, Tewanima’s great-nephew and president of the committee that organizes the run. Indeed, the racers, be they Hopi, Navajo, Zuni or WASP, are all warmly received in a way that puts most such events to shame. The number pickup the night before the race is as much social event as anything, where a group of local women pile plates high with pasta, green chiles and more. Nearby, a group of volunteers works to drain the baseball field/starting line of a huge puddle brought by that day’s deluge. The Hopi Cultural Center hotel, the only lodging establishment nearby, is teeming with runners from all over, and is chock full for the night. Though it’s still officially summer, a chill, and a light fog, hang over the mesa as runners congregate at the starting line. A good-sized crowd of spectators is not deterred, though, and gathers around to lend encouragement and cheers. Runners gather haphazardly on the line and in the still-sunless dawn, Nikki Qumyintewa, this year’s Miss Hopi, gives the starting order via megaphone.

Bawcom mixing it up with the men doesn’t seem to enflame any machismo resistance. In fact, there’s a famous story, recounted by Harold Courlander in The Fourth World of the Hopis, about a running race between the old villages of Payupki and Tikuvi. The fastest runner from Payupki is a young woman who can run circles around her brother and, to his astonishment, still grind corn afterwards. Her Tikuvi rival, a boy, is transformed into a dove at one point during the race, and takes the lead. But the Payupki runner has Spider Grandmother on her side (sitting in her ear whispering instructions). The woman wins.

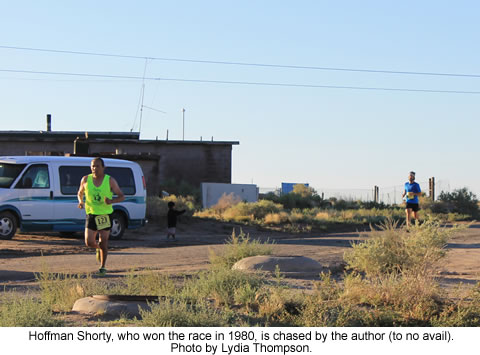

But that’s okay, because this isn’t just some weekend runner, it’s Hoffman Shorty, who crushed the competition in this race back in the late 1970s and early 1980s and was immortalized in Ed Abbey’s story, “Footrace in the Desert,” about the 1980 Tewanima run. Abbey actually started the race that year, less than a decade before he died. But he dropped out after the first mile to concentrate on his “journalistic duties,” and wrote about Shorty, a Navajo, taking an early lead and then pouncing the mostly Hopi field by a quarter of a mile or more. This year, I dig deep to keep Shorty in sight, figuring my relative youth might enable me to pass him on the final climb. I am wrong.

As we watch the one- and two-mile racers – many of them young children, some running in skirts – a local spectator and I start talking. The last mile of the race includes a brutally steep climb up to the mesa top, much of it on steps carved from sandstone. On my climb I also noticed a parallel trail of hand and footholds – so-called moqui steps – next to the main path. I ask the man if he knows about the trail, how old it is, and what it’s used for. The local smiles and tells me a long, wandering story about running out into the desert and hunting rabbits with throwing sticks and the farms at Moencopi. He bemoans the changes that have occurred – the old stone houses replaced by trailers, the power lines transecting the blue sky. He tactfully avoids my questions about the steps. I read somewhere that the Hopi consider trails to be the veins and arteries of every village, and that running on them keeps the village vital. If it’s true, I’m happy to have done my part. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2013 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2013 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Today’s

race, organized by Tewanima’s kin, celebrates the Olympian’s

legacy with a 10k, 5k, two-mile and one-mile run, and is a continuation

of a tradition of running that dates back hundreds of years. It

draws a total of some 300 runners from Indian Country and beyond,

giving participants a glimpse of a Hopi that they might not otherwise

see.

Today’s

race, organized by Tewanima’s kin, celebrates the Olympian’s

legacy with a 10k, 5k, two-mile and one-mile run, and is a continuation

of a tradition of running that dates back hundreds of years. It

draws a total of some 300 runners from Indian Country and beyond,

giving participants a glimpse of a Hopi that they might not otherwise

see.

A

lead pack, moving at a blistering pace, soon establishes itself.

In it are a group of aerobic torpedoes like the pony-tailed, teen-aged

A

lead pack, moving at a blistering pace, soon establishes itself.

In it are a group of aerobic torpedoes like the pony-tailed, teen-aged

To

my middle-aged legs, it seems as if Bawcom, Begay and the others

are also relying on magic as they float gracefully through the village.

After about a half mile, I abandon my futile quest to keep them

in sight and enter into a more age-appropriate rhythm, and for a

while, I have the trail to myself. About two miles into the run,

however, I’m caught and then passed. In his fifties, with a

thin black braid laced with silver, my new nemesis runs lightly

on thin calves and ankles. His posture is almost rigid, his head

and shoulders not bobbing at all. To the volunteers along the way,

offering water and a soft-spoken “askwali” or “kwahkway,”

I imagine I must look like a flailing, slow beast behind this guy.

To

my middle-aged legs, it seems as if Bawcom, Begay and the others

are also relying on magic as they float gracefully through the village.

After about a half mile, I abandon my futile quest to keep them

in sight and enter into a more age-appropriate rhythm, and for a

while, I have the trail to myself. About two miles into the run,

however, I’m caught and then passed. In his fifties, with a

thin black braid laced with silver, my new nemesis runs lightly

on thin calves and ankles. His posture is almost rigid, his head

and shoulders not bobbing at all. To the volunteers along the way,

offering water and a soft-spoken “askwali” or “kwahkway,”

I imagine I must look like a flailing, slow beast behind this guy. Begay

wins the year’s race in just 40 minutes and 13 seconds, a dozen

seconds faster than the record he set the year before. Anthony Masayesva

is just thirteen seconds behind, nipping his brother Brian at the

line. Trent Taylor – another relative of Tewanima – is

in fourth, with Bawcom rounding out the top five. By the time I

finish, far behind Begay and company and a good half-minute behind

Shorty, most of the village has gathered at the finish line to cheer

the runners on and sell them breakfast: A burrito with eggs, sausage,

potatoes and, in some cases, Spam; or a yogurt and fresh fruit parfait.

Begay

wins the year’s race in just 40 minutes and 13 seconds, a dozen

seconds faster than the record he set the year before. Anthony Masayesva

is just thirteen seconds behind, nipping his brother Brian at the

line. Trent Taylor – another relative of Tewanima – is

in fourth, with Bawcom rounding out the top five. By the time I

finish, far behind Begay and company and a good half-minute behind

Shorty, most of the village has gathered at the finish line to cheer

the runners on and sell them breakfast: A burrito with eggs, sausage,

potatoes and, in some cases, Spam; or a yogurt and fresh fruit parfait.