|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

January

2013 - Volume 11 Number 1

|

||

|

|

||

|

Oklahoma Schools

Push to Keep Native Languages Alive

|

||

|

by Lynn Armitage

Indian County Today

|

||

|

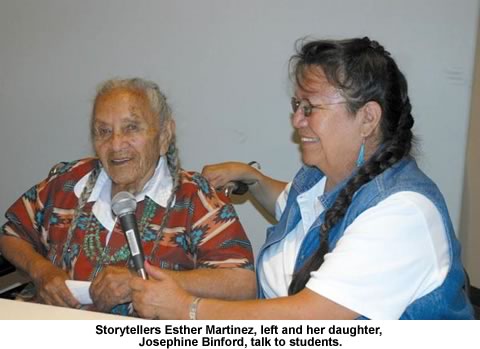

credits: photo courtesy

of Indian Country Today

|

| On September 13, the U.S. House and Senate

introduced bipartisan legislation to continue funding that will help

keep Native American languages alive and spoken throughout our country’s

tribal communities. The

Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act, first

funded in 2008 and set to expire at the end of this year, has funneled

more than $50 million into tribal language programs.

Impassioned sponsors of the bill understand the crisis facing Native American languages today. Many languages are endangered and could very well disappear in the next decade if something isn’t done to pass them on to younger generations. According to UNESCO, there are 139 Native American languages in the United States—some spoken by only a scant number of elderly tribal members. UNESCO claims that more than 70 of these languages could die off completely within five years if immediate efforts aren’t made to preserve them. Language advocates agree that it would be a tragedy to lose even one more Native language, as each language carries with it the rich history, values, wisdom and spiritual beliefs of a tribe. As one indigenous language instructor recently: “Our language is the number one source of our soul, our pride, our being, our strength and our identity.”

One survey says nine different Native

languages are taught in up to 34 public schools, K-12, all over

Oklahoma: Cherokee, Cheyenne, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Comanche, Kiowa,

Osage, Pawnee and Ponca. Desa Dawson, director of World Language Education for the Oklahoma State Department of Education, says 1,355 elementary and high school students in Oklahoma are taking Native American language classes this year as their world language requirement. Why the intense interest? “We’re Oklahoma, for heaven’s sake!” Dawson says, adding that while students—both Native and non-Native—take these language classes to satisfy either a foreign language credit or as an elective, there are other things that draw them in: “It’s an opportunity for Natives who aren’t immersed in the language at home to learn more about their heritage; and [for] non-Natives [who] are surrounded by so many tribes here in Oklahoma, there is a natural curiosity about them.” Dawson, who speaks Spanish fluently and knows a few Native words (for hello and thank you), says the biggest challenges facing language education in the schools are a lack of teachers fluent in tribal languages and a lack of language textbooks. “Teachers make their own materials, and sometimes tribes furnish what is needed in the classroom.” She says several groups are tackling the first problem. The Oklahoma Native Language Association is working hard on the professional development of language teachers, and several tribes have created their own language-learning departments from within. One success story comes from the Sac & Fox Nation from Stroud, Oklahoma. Dawson says the tribe had fewer than five people who spoke Sauk, their native tongue, as their first language, and they were all more than 70 years old. The tribe started a special program in which aspiring teachers of Sauk were schooled by Native speakers 15 to 20 hours a week. As a result, four more teachers have become fluent in Sauk and a language program is being developed for the local high school to help grow even more speakers. Start Young, Very Young To this end, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma started a preschool language immersion program where young children who are just learning how to speak are taught and spoken to in their native tongue only. Enrollment at the Mvnettvlke Enhake immersion school is currently at six students, from 6 months to 3 years old, with 10 other children on the waiting list. After the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma learned from a survey conducted 10 years ago that no one under the age of 40 was conversational in their language, the tribe kicked into high gear. It started a language-immersion school, which began as private preschool in 2001, where preschool and elementary students would hear and speak nothing but Cherokee all day. The Cherokee Immersion School recently became a public charter school and now receives some funding from the state. The school made history this year when it graduated its first class of nine students. The Old College Try While Linn says these Native languages aren’t difficult to learn, the challenge comes in how often—and where—they can be spoken outside the classroom. “You do not get enough exposure to the language or enough time to practice speaking in 50 minutes, even five days a week,” she says. “It is not just a disadvantage to University of Oklahoma students learning these languages; it is why these languages are endangered.” Northeastern State University in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, is doing what it can to keep languages in the state off the endangered list. Through the Department of Languages & Literature, students can earn a bachelor of arts degree in Cherokee language education that will prepare them to become teachers and speakers of the language. At Southeastern Oklahoma State University in Durant, Oklahoma, students can earn a minor in Choctaw through the English, Humanities & Languages department. For students at Southeastern Oklahoma State University who are intent on becoming a Choctaw language teacher, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma Language Department offers a full scholarship that includes tuition, fees, books, a living stipend of $1,500 per month, tutoring, testing fees, relocation-assistance stipend (if necessary) and laptop computer and printer. For more details, visit ChoctawSchool.com. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2013 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2013 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Oklahoma

Schools Step It Up

Oklahoma

Schools Step It Up