|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

January 2013 - Volume

11 Number 1

|

||

|

|

||

|

Spiritual Home

|

||

|

by Jackie Jadrnak /

Albuquerque Journal North Reporter

|

||

|

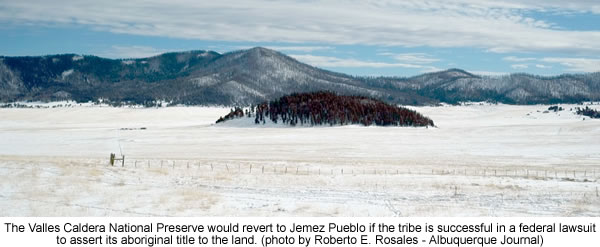

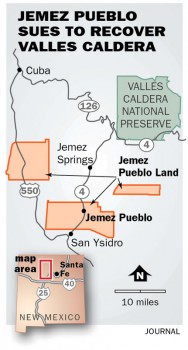

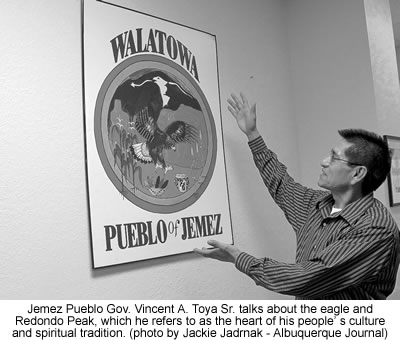

JEMEZ PUEBLO — For generations, people of Jemez Pueblo have asked what they are doing in the valley where their current home of Walatowa sprawls, according to Pueblo Gov. Vincent A. Toya Sr. "We used to be up on the mesa area," he said. "We're mountain people, yet we ended up down here." Now, the pueblo is trying to get at least a piece of that ancestral mountain homeland back under its control. It has filed a complaint in federal court to recover all the land now contained within the Valles Caldera National Preserve. "All our songs, our traditional calendar, refer to this area," Toya said, sitting at a table Friday in the tribal administration building. "It is so dear to us, because it has everything in our heart up there." Redondo Peak, referred to as Wav e ma by the Towa-speaking people, contains a profile of an eagle with a lightning bolt coming from its beak. This was the sign the ancestors were told to look for when they were given a migration route from the place of emergence in the Four Corners, Toya said. More than seven centuries ago, they came to set up villages throughout the area of the Jemez Mountains — more than 60 archaeological sites have been found linked to Jemez ancestral people on the western side of the mountains, according to the federal complaint filed in July. Redondo Peak served as the sacred and ceremonial center. In testimony before a Senate committee concerning the Valles Caldera National Preserve, then-Gov. Joshua Madalena put it this way: "The Valles Caldera is our cathedral. It is just as important for us as the Vatican is for Catholics, and as the famous Blue Lake is to Taos Pueblo.

Toya said the board of trustees that runs the preserve has been very open and cooperative with the Jemez people in getting access for ceremonial and other activities. He hopes to maintain their good will, he said, as the Pueblo attempts to get the land back as its own. Terry McDermott, spokesman for the preserve, said the board would not comment on any pending litigation. The U.S. Department of Justice is defending the case. Elizabeth Martinez, spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney's Office in Albuquerque, noted that office is due to file a response to the complaint in mid-February. She said the attorneys would not discuss their legal arguments before then. Jemez has the support of other pueblos in its effort, getting a 14-0 vote Dec. 3 from the All Indian Pueblo Council endorsing the return of the Valles Caldera to the Jemez people. Aboriginal land The concept of aboriginal Indian title has its roots in Spanish colonial law, with the United States government then adding another layer assuming U.S. ownership of the land, according to Thomas Luebben, the Albuquerque attorney representing Jemez Pueblo. There are three ways that Indian right of occupancy can be terminated, he said: if the land is ceded in a treaty, if a tribe officially has abandoned the land, or if an Act of Congress asserted ownership of the land. "In this instance, Congress never did that," Luebben said, adding that neither did the other two actions take place. Instead, in 1860, the heirs of Luis Maria Cabeza de Baca got 99,289 acres that included the Valles Caldera as part of a settlement for a Mexican land grant that happened to conflict with the Town of Las Vegas (N.M.) Community Grant, according to the Pueblo's court filing. "Interestingly, the U.S. never issued a deed to it," Luebben said. "And they never dealt with the subject of the Jemez Pueblo aboriginal title." On July 25, 2000, the U.S. government purchased some 94,761 acres from the Dunnigan family, who owned the land then, for the Valles Caldera National Preserve.

As far as he knows, Luebben said, this is the first time that a tribe has sued to regain land under the quiet title act that Congress adopted in the mid-1970s, giving people the right to sue the federal government to contest its land ownership. "In the whole history of civil rights, the U.S. has never been able to bring itself to do the right thing about Indian land," Luebben said, adding that he's not advocating the return of the entire continent to tribal people. "If there's a town, that's one thing. But, in the Valles Caldera, no one lives there." What to do with land? When the word "casino" comes up, Toya exclaimed, "No, no, no!" But, he added, that was only his perspective. The people of the Pueblo have yet to come together to make a plan on what they want. After all, the legal battle could drag on for years. "There are many preliminary thoughts," Toya said, mentioning recreational use and eco-tourism. The preserve's current board of trustees has been approached by many "entrepreneurs" who want to develop businesses in the Valles Caldera, and the Pueblo would probably be hit with the same sales pitches if it gains control, he said. Most likely, the Pueblo would build on what the preserve has already been doing, he suggested. Any development would likely be in line with current usage of the preserve, such as adding a hunting or fishing lodge, he said. The Pueblo is doing a feasibility study on the economic viability of Valles Caldera, Toya added, looking at how to maximize the recreational opportunities and economic benefits to the area. In any case, the Pueblo would want to allow public access. "We'll let Tom go fishing if he wants to," Toya said, smiling at Luebben.

Valles

Caldera National Preserve |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000 - 2013 of Vicki Williams Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999 - 2013 of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

"It

is where the spirits of our ancestors reside, and it is our most

important spiritual place."

"It

is where the spirits of our ancestors reside, and it is our most

important spiritual place." The

Pueblo had a 12-year period in which to contest that federal ownership

and assert its aboriginal rights, Luebben said. That happened with

last July's federal court filing, just before the deadline.

The

Pueblo had a 12-year period in which to contest that federal ownership

and assert its aboriginal rights, Luebben said. That happened with

last July's federal court filing, just before the deadline.