|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

June

1, 2011 - Volume 9 Number 6

|

||

|

|

||

|

Centuries of

Interruption and a History Rejoined

|

||

|

by Brian McGrory - Boston

Globe Columnist / May 11, 2011

|

||

Commencement

season is arriving in this grand metropolis, the higher education

capital of the world. Every graduate has a story. Tiffany Smalley’s

just happens to be 346 years old. Commencement

season is arriving in this grand metropolis, the higher education

capital of the world. Every graduate has a story. Tiffany Smalley’s

just happens to be 346 years old.

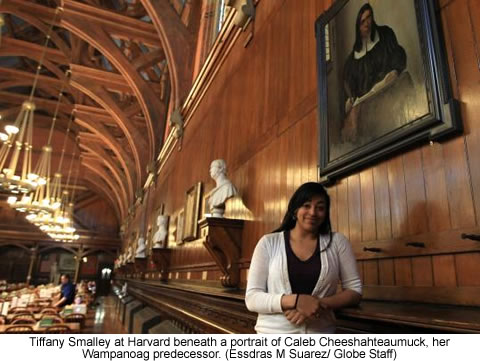

She sat in a Harvard Square coffee shop one recent morning telling it in the understated way of hers, repeatedly talking about two young men, Caleb and Joel, Joel and Caleb, as if they might breeze through the door and start hashing over weekend plans. The familiarity, even the affection, is understandable. They are all Wampanoag Indians, these three. They are accomplished people. They all left Martha’s Vineyard to prosper over four years at Harvard. There is, however, a key distinction: Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck and Joel Iacommes hark from the 1600s, while Tiffany, sipping a Frappuccino and rushing off to an internship, is every bit of the modern world. Come May 26, the bond between Smalley and both her ancestors will come full circle. That is the day she will stride across the stage to accept a diploma and become the first Wampanoag to graduate from Harvard College since Caleb received his degree in 1665. “The connection, recognizing those roots, is really important to feeling at home here,’’ Smalley said. “And I’ve felt really at home, knowing Caleb did this. It gives you perspective. He was just thrown into it, and for him, it was a whole different world.’’ That connection will be realized with Joel on commencement day in an even more extraordinary way. Harvard officials plan to announce today that the university is granting a posthumous degree to Joel Iacommes, Caleb’s classmate who was killed in a shipwreck while he visited his family on Martha’s Vineyard just before graduation. Nearly 3 1/2 centuries later, Smalley will accept the diploma that has been lost in the dust of time. The awarding of the degree will have various meanings to different people. For the record keepers, it will be, almost certainly, the oldest posthumous diploma ever given in the United States. For Harvard, it marks a new front in rediscovering and highlighting its heritage as a university chartered to educate Indians alongside Puritans. For the Wampanoags from Aquinnah and Mashpee, it is a triumphant dose of hard-earned recognition. And for Tiffany Smalley, it is simple justice for a young man who didn’t live to claim what he so richly earned, and has lately been lost in the growing shadow of his more prominent tribe member, Caleb. Harvard officials unveiled a portrait of Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck in December. And he is being introduced to the larger world as the namesake character in “Caleb’s Crossing,’’ a historical novel written by Pulitzer Prize winning author Geraldine Brooks and published last week to early rave reviews. “Caleb’s gotten a lot of shine this year,’’ Smalley said. “And now, finally, it’s Joel’s turn.’’ Left unstated is the profound accomplishment of Smalley herself, the brainy, dimpled student described by Harvard historian Lisa Brooks as “an amazing young woman.’’ “This is a place full of leaders, full of intelligent and prominent students,’’ Brooks said. “Tiffany is all of those things, and she is carrying a great legacy and much humility.’’ Smalley has been deeply involved in the push by Harvard to reconnect with its Indian roots. She was among the many students who have embarked on an archeological dig for the last several years in the area of Harvard Yard where the Indian College once stood. They also built a wetu, or Indian hut, on campus. Harvard president Drew Faust was on the phone recently saying that the dig, occurring just outside her window, was unearthing essential truths along with artifacts. “We’ve been rediscovering the history right before our eyes — literally,’’ she said. “It’s focused a lot of attention on our Indian origins.’’ Those Indian origins run true and deep, though not consistently. The school stipulated in its 1650 charter that the goal was “the Education of the English and Indian Youth of the Country,’’ a mission that attracted much-needed money from England in the name of converting Indians to Christianity. Henry Dunster, the university’s first president, envisioned Harvard as “the Indian Oxford as well as the New English Cambridge.’’ Joel and Caleb, sons of Wampanoag tribal leaders, were sent to preparatory school in Roxbury and Cambridge, then entered Harvard in 1661, to be educated alongside five Englishmen. They became fluent in Latin, Greek, English, and enough Hebrew to read parts of the Old Testament. “By all accounts, Joel and Caleb excelled at college,’’ said Brooks, the historian. “They were as good, or better, than their English classmates.’’ Despite the early success, the mission — and missionary work — came to an abrupt halt in 1675, with King Philip’s War. The Indian College was torn down by 1698. Harvard basically pushed aside the Indian tenets in its charter, until the 1970s, when recruiting began anew. When Smalley was a high school sophomore, she visited Harvard as part of a six-week program geared toward Native American students and quickly became enamored of it. Neither of her parents graduated from college. The oldest of three siblings, she came from a secluded community on the Vineyard. But she remained undaunted. “I imagined everyone would be extra smart and stuck up,’’ Smalley said. “But everyone’s been really down to earth. Smart, yes, but down to earth.’’ By last fall, 2.7 percent of the incoming freshmen were of Native American descent, by every measure a banner year for recruitment at Harvard, though that number fluctuates significantly from year to year. Some have begun pushing for Joel and Caleb scholarships for Native Americans. Faust herself said she hopes the attention on the posthumous degree “will draw the attention of Native Americans to Harvard.’’ But for now, for Native Americans, it’s a moment to celebrate. “It means a lot to us as a tribal community that Joel was one of ours, and to Indians across the country that we had Indians graduating from Harvard in 1665, not one, but two,’’ said Cheryl Andrews-Maltais, chairwoman of the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe. And some 346 years later, for the Wampanoags, a third one as well. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010,

2011 of Vicki Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011

of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||