|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

April

1, 2011 - Volume 9 Number 4

|

||

|

|

||

|

Language Preservation

Vision Shared for all Tribes

|

||

|

by Donna Laurent Caruso

- Indian Country Today

|

||

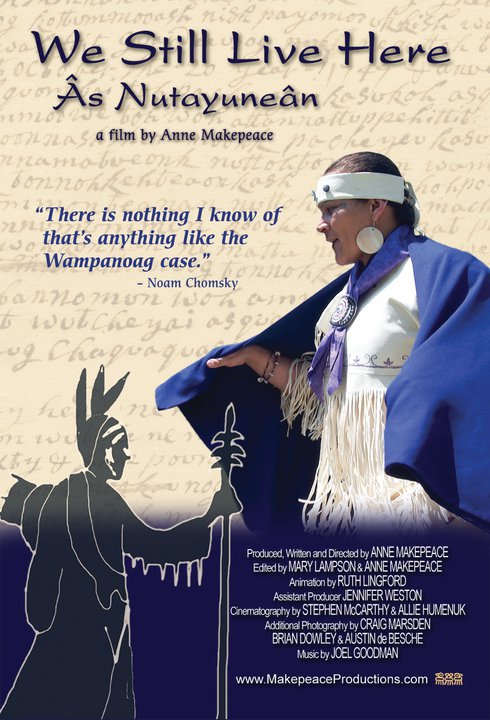

“If

the Wampanoag could bring back their language without a single Native

speaker, then anything is possible,” Anne Makepeace, the creator

of a documentary about the revitalization of the Wôpanâak

language said. “I think this film can serve as a cautionary tale

for Native people whose languages are endangered and a model of inspiration

for those working to preserve and revitalize their languages.” “If

the Wampanoag could bring back their language without a single Native

speaker, then anything is possible,” Anne Makepeace, the creator

of a documentary about the revitalization of the Wôpanâak

language said. “I think this film can serve as a cautionary tale

for Native people whose languages are endangered and a model of inspiration

for those working to preserve and revitalize their languages.”

The Wampanoag people greeted and helped the Pilgrims but ultimately lost most of their land; their language had not been spoken in a century. “We Still Live Here Âs Nutayuneân,” opens with Jesse Little Doe Baird (Mashpee Wampanoag) driving past Wampanoag place name signs while traveling from Mashpee to the ferry for Martha’s Vineyard. Baird lives there in a home built by her husband, Jason Baird, who is also the medicine man of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah), and their 6-year-old daughter, who is now the first Wampanoag to speak their ancestral language from childhood. While waiting for the ferry, Baird, who has been speaking Wampanoag for over a decade, tells us of her visions: “It was prophesied that language would go away from us and when the appointed time came, there would be a way made for the language to return.” She explains that the ancestors requested her to first ask other Wampanoag people whether they wanted the language home. She asked the groups (beginning with Mashpee and Aquinnah) and it was agreed they wanted to bring their language home. Her question brought communities together and “this never happens,” Baird said, smiling. Baird had been co-director since 1993 of the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project (with Helen Manning, Aquinnah Wampanoag, now deceased). Baird ultimately earned a master’s degree in linguistics in 2000 at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), working alongside scholar of indigenous languages Ken Hale, a descendant of colonists. The filmmaker is also a descendant of colonists “who stole their land,” Makepeace admits. Initially angry that she would need the help of “a white man” to take the next steps for her language programs, Baird’s dreams clarified that the descendants of those who broke the circle of language would be vital to close the circle again. Last September, Baird’s work was recognized with a MacArthur Foundation genius grant of $500,000. That same week, The Wôpanâak Language Project was awarded a $530,000 federal grant. The foundation wrote, “Wampanoag was spoken by tens of thousands of people in southeast New England when 17th century Puritans/missionaries learned the language, rendered it phonetically in the Roman alphabet and used it to translate the King James Bible for the purpose of conversion. Baird…is providing precious links to our nation’s complex past.” Makepeace’s film shows some of the original documents written in Wampanoag that Baird used to create her dictionary, grammar, and school lessons: deeds, letters, petitions, even notes in the margins of family bibles. Baird’s dedication is captured in the documentary; you may find yourself whispering your own first new phrases. The documentary shows how Baird learns new words using vowel and pronunciation charts, and dictionaries from one of the 40 Algonquian languages that are still spoken, such as Passamaquoddy. It also shows students in the classroom, and sometimes, learning “Wamp” does not look easy. Tobias Vanderhoop, tribal administrator, Aquinnah, describes how children, and therefore language and culture, were taken. The camera scans an original English document and you read each column: An unnamed child, their sex, then age, then price and place they’re sent. Fifteen years later, the children might return home from servitude in places like Lexington or Cambridge. “I think it pleases the Creator,” said Eva Blake (Assonet Wampanoag), in a voice-over while the film shows the viewer a recent Aquinnah pow wow. Because of Baird’s work, we learn one of the many Wampanoag creation stories and Makepeace devises a way to tell us by using a series of animations that solve the cultural and language problem of presenting Natives’ dreams. The animations were created by Ruth Lingford, professor of animation at Harvard. Just this February, Baird was in Hale’s hometown of Lexington, Massachusetts giving a presentation. Coming full circle, she told a children’s story that she wrote: Sâpaheekanuhtyâtôn (Let’s Make Soup). Visit the Makepeace Productions website for ordering information and clips from the film. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010,

2011 of Vicki Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011

of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||