|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 1, 2010 - Volume

8 Number 12

|

||

|

|

||

|

Northern Arapaho

Seek To Restore Historic Link To Buffalo

|

||

|

by Tom Mast - The (Casper,

WY) Star-Tribune staff writer

|

||

|

On the other side, a band of people waits. In 1889, a Paiute prophet saw buffalo returning, and spread the good news among Northern Arapahos and other plains people. Those hopes turned to bitter tears. But a hundred years on, Arapaho elders were dreaming buffalo again. "When we getting our buffalo?" people ask. It's a question J.T. Trosper, a burly man with mustache and black ponytail, hears often these days. "It could be a while," he responds. There are buffalo sources, fences and finances, to think about first. In the spring of 2009, Trosper was certain the buffalo would come. But turbulent waters blocked the way. Arapahos and bison have come down the same road. Even as a tiny remnant of the Buffalo Nation survived in Yellowstone National Park, the last Northern Arapahos bunched together on the Wind River reservation. "The white people wanted to come and take our land, take everything away from us, and they couldn't do it for quite a while because we fought them, we resisted," Trosper says. "And as long as we had buffalo, we could do that. And they recognized that the way to beat us wasn't to fight us, it was to kill buffalo. If they kill the buffalo, they kill us. And that's what they did." "But we didn't die. We both grew and survived, and we're carrying on now," Trosper says. "And now it's time to bring that connection back."

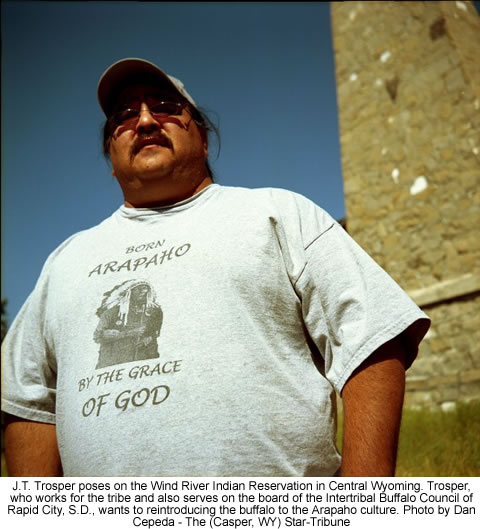

Rough stone structures, arranged in a circle, comprise the Episcopal mission of St. Michael's. A circular hearth sits at its heart, with a buffalo symbol etched in concrete. Once, buffalo here were flesh and blood, though memories about when prove elusive. Perhaps it was the 1970s? St. Michael's provided a young J.T. Trosper a first glimpse of the Buffalo Nation; just a few head confined in a corral, and a child who did not fully comprehend the totality of their presence, in history or tradition. Still, he says, "I knew they were important to us." One day, the buffalo just disappeared. Trosper, 45, works for the tribe, tasked with creating a plan for buffalo. He also serves on the board of the Intertribal Buffalo Council of Rapid City, S.D., which has helped many tribes with buffalo herds. Trosper makes cell-phone calls, surfs the Web for buffalo facts, talks with officials and tribal members, all the while negotiating a way for buffalo onto Arapaho land. It has been talked about for nearly two decades; Trosper has come closest to making it happen. Trosper operates with scant administrative tools. His office consists of a back-row seat at the Wind River Tribal College computer lab, or the driver's side of his pickup. He wears a T-shirt to work: "Born Arapaho," it reads, "By The Grace of God." More than material, encouragement of tribal elders has sustained him. "It's for us, our Arapaho people, to remember and thank those buffalo for what they did all those years," he says. "We got to provide them a home now, just like they provided for us all those years." For Trosper, Yellowstone bison enjoy serious credibility. Wild and free, blessed with good genetics, they embody a time before white settlement. The rub is brucellosis.

In 1901, only about 25 wild buffalo remained in Yellowstone National Park. The U.S. Army, no ally of buffalo during the Indian wars, helped save the herd from extinction. In 1917, officials discovered brucellosis in Yellowstone bison, a bacterium that can cause cows to abort their calves. They probably contracted the disease from domestic cattle raised to provide milk and meat to park visitors. For livestock producers, brucellosis is no trifling matter. The disease can result in quarantine, government destruction of cattle and big financial losses. The U.S. Department of Agriculture declared war on brucellosis in 1934; billions were spent over the next 70 years toward eradication efforts. By February 2008, the USDA announced that for the first time, all 50 states could be declared brucellosis free. The disease has since cropped up again in Wyoming cattle. At the same time, conservation of Yellowstone's bison succeeded admirably, and they rebounded from the brink of extinction. The herd now numbers about 3,900 head. Yellowstone buffalo are among the most important anywhere: free-roaming, with no evidence of genetic mixing with cattle and ranked high for genetic diversity. Accordingly, they have excellent potential for starting new herds. But brucellosis persists in Yellowstone. Inherent tension between buffalo and cattle ranchers erupted in the winter of 1988-89. Great wildfires burned over much of Yellowstone Park the previous summer, destroyed large areas of grass and sagebrush, as well as timber. Cold and snow forced buffalo to roam far afield in search of food. The state of Montana opened a special season on hungry bison leaving the park. In scenes reminiscent of the 19th century, hundreds were shot, many in burrow pits along U.S. Highway 89 between Gardiner and Livingston. But this time, the carnage made the nightly news. The hunt became a bloody spectacle, in full public view. "We became a pariah in the nation," says Joe Gutkoski, president of the Bozeman-based Yellowstone Buffalo Foundation. "[In 1989] we lost 50 percent of our tourist trade." By Gutkoski's count, more than 5,000 Yellowstone buffalo have been slaughtered since the winter of 1988-89, including more than 1,300 shipped from Yellowstone Park in 2007-08 without even being tested for brucellosis. In 2008, the federal Government Accountability Office found serious flaws with the interagency management of Yellowstone's buffalo. Some changes ensued; however, criticism and lawsuits have continued. But the controversy also produced an opportunity. And Trosper, on behalf of the Arapaho people, tried to make the most of it.

Jack Rhyan, a brucellosis expert for the USDA, helped lead an effort to determine if Yellowstone buffalo that tested positive for brucellosis could be successfully separated from those that would remain negative over time. The goal, essentially, was to explore management options for dealing with extra bison that did not involve meat hooks, and thereby preserve their excellent genetic traits. The project, launched in 2005, examined possible latency of brucellosis in bison. A quarantine facility was constructed in Montana, and frequent blood tests monitored calves for the presence brucellosis antibodies. Those that cleared the rigorous process were ready for release in the spring of 2009. A call went out to find the bison a home. Three tribes responded, including the Northern Arapaho. The Arapahos were deemed best prepared. Fittingly, a buffalo range would be established on the Arapaho Ranch -- in some ways, a remnant of America before Christopher Columbus. By this point, ranch manager David Stoner says, wildlife officials expressed little worry about brucellosis, and he shared their confidence: "This was the cleanest group of ungulates in the country." Of greater concern were good fences to keep buffalo from wandering off the ranch. Of course, the General Council, made up of Arapaho adults in sufficient number to constitute a quorum, needed to provide its blessing. But that seemed like a foregone conclusion. In all his work to bring buffalo back, Trosper had heard nary a negative word. The stars were aligned, or so it seemed. "Why would I be worried?" Trosper says. "We're Arapaho people, and that's our culture ... We were about four or five days away from them actually being here. I wasn't worried about it." Then he adds, "I guess I should have been."

Forty-one Yellowstone buffalo were intended for the Arapaho Ranch; they would form the core for a herd of 300. A setting for bison more fitting than the Arapaho Ranch is hard to conceive. At 595,000 acres, it runs nearly 100 miles east to west in the heart of central Wyoming, from the Wind River Canyon to Washakie Needles, roughly twice the size of Grand Teton National Park. Much of the land remains unspoiled. Fresh springs and streams flow across the varied land, with elk and bear, wolves and bighorn sheep. The ranch raises cattle, including about 3,000 mother cows, in a manner that mimics the natural order. No chemicals are applied, no growth hormones, no genetically modified seed, no antibiotics. The beef is certified organic. "The tribe embraced it completely," says Stoner, 58, who listens to opera while attending to ranch details. "It fits their belief system, that they are part of the land. They're a guest here." The Arapaho Ranch began in 1940. In the days before casinos, it was a rarity -- a successful, tribally owned enterprise. Ranch management reflects a traditional belief that the earth must be respected. "The tragedy of reservations, and the breaking up of the ways of life of American Indians, is that they didn't believe in land ownership," Stoner says. "The land belonged to everyone. And everyone had a responsibility to take care of the land, and the resources." Not all people are enamored of the Arapaho Ranch. Some grumble that its benefits are not spread sufficiently among tribal members, but for many, it continues to be a powerful symbol. "As it became more successful, it really was a great source of pride for the tribe," Stoner says. But buffalo also resonate, as a potent cultural icon. "The buffalo were here first," says Alonzo Moss Sr., an Arapaho elder who wryly introduces himself as Buffalo Bill. "Just like us were here before you guys." "This is their land. Not the cows'." Even so, much has happened since buffalo grazed the plains. Two world wars, fast foods and space shots to the moon, automobiles and the Internet, all passed by, as buffalo became strangers in their own country. In an economic sense, cattle became today's buffalo. Families depend on them to make ends meet. Range units divide the reservation, and permits to graze animals pass down like family wealth. Preston Smith, a range management specialist for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, says some ranches have annual receipts of $100,000 -- not large by Wyoming standards, but the basis for a living in an area with historically high unemployment. Two women share a meal at the Ethete Senior Center, talking about buffalo. Soon, ambivalence becomes apparent. Buffalo are good for the tribe, yes, but ... "As long as they're not with our cows," Georgie Crawford says. "They carry brucellosis, and once they get it, our beef that we have is not worth selling." And the Arapaho Ranch? "Aaahh, that's a cow operation," exclaims a man in soiled work clothes. No buffalo there.

What happened at the General Council in April 2009 depends on who you talk to. Brucellosis, and the specter of the state killing off the tribe's infected cattle, played prominently. Perhaps it was bad timing, or a meeting just gone on too long. Or maybe the idea hadn't been explained enough, or some elders didn't follow the fast flow of English words, or the resolution was poorly worded. Uncertain, even fearful, some people abstained; and on a close vote, the Yellowstone buffalo were turned back from the Arapaho Ranch. Culture notwithstanding, maybe it was just a dream after all.

The rattlesnake may have seen it coming, coiled defensively as if to strike and tattooed against the pavement. Perhaps it was a big RV, carrying summer vacationers to Yellowstone, which turned the snake into a highway decal. The road ditches to Ethete crawl with grasshoppers; a coyote-size dog, gray and lean, scratches for some morsel in the dry grass. At first sight, life on the Wind River reservation seems bare and disjointed. Ethete consists of a few tribal buildings, a convenience store, an old Christian mission and a stop light. Houses colored a blue-gray sameness dot the prairie, horses in the front yard, rotting car hulks out back, piles of kids' bicycles and basketball standards, a traditional sweat lodge covered with a blue plastic tarp. In the Hines General Store, a few miles away, there's beef in the grocery display. But for buffalo, traditional meat of the Arapaho diet, check JB's in Lander, a tourist town off the reservation. The only bison seen regularly around Ethete nowadays sing like steam calliopes as middle-age women watch for their luck to turn up on the Little Wind Casino's "Buffalo" penny slot machines. The aim of acculturation was extinguishment of self. "The sooner the Indian youth is thrown among the whites the better his chance for making a livelihood when a man," the U.S. government declared at the dawn of the reservation era. "The Indian is essentially imitative and will soon learn the white man's ways when forced to ..." Arapaho elders, though gracious and modest, seem beleaguered. Language and traditions have splintered under the weight of repression and absorption, and inevitable social change over the course of a century. Such incongruity to the Arapaho way comes out sideways. High school graduation rates are the lowest in the state. Alcohol and drug abuse are widespread; American Indians and Alaska Natives suffer the highest rates of diabetes in the country. Among more than 9,200 enrolled members of the tribe, only about 250 people still speak Arapaho fluently. "Right now, everything's extinct, just like the buffalo are," Ruth Big Lake says. "Time has gone by so fast, it's our kids who are the ones that's lost. They're lost. They're not within our circles. It's like they're drifting away from us. These different avenues that they get into are no good." Old and young, people frequently point a finger at drugs and strong drink. Ruth the elder envisions a long period of sustained intervention; not in a substance abuse sense, but culturally, speaking the language and bringing in buffalo like spiritual mentors. Priests at boarding school tried to beat the Arapaho out of 72-year-old Alonzo Moss Sr. It didn't work. In books and other forums, Moss strives to keep the language alive. "It's got to start with your ceremonial people," he says. "They've got to keep the language alive by speaking all the time. No using English in ceremonies." William C'Hair compares his culture to a braided rope, the strands of which have become confused. He talks about circles embedded in the universe, in atomic nuclei and orbiting electrons, teepee rings and long cycles, the lives of buffalo and Arapaho people. But with the buffalo gone, the circle of life has been disrupted, and the natural order undermined. That circle is now broken, William C'Hair says. "But the buffalo would heal it." When asked about efforts to start a buffalo herd on Arapaho land, some young people merely shrug. But not all. "Right now our way of thinking is based upon the white man world. In my opinion, most Arapahos don't think like an Arapaho," says Randee Iron Cloud, 23, a student at Wind River Tribal College. "It wasn't like they chose that road. It's what was being offered at the time. But I think we need to start thinking like Arapaho again. The buffalo here, that can only get us a step closer to where we want to be."

After the General Council's decision in April 2009, a scramble ensued. Rejected by the Northern Arapaho, the Yellowstone herd found itself marooned. Mike Volesky, natural resources policy adviser to Montana Gov. Brian Schweitzer, said a casual encounter between Schweitzer and a manager for one of Ted Turner's ranches led to the bison being transferred to the media billionaire's Green Ranch. Despite the setback, it wasn't long before Trosper had buffalo on the agenda again, which the General Council didn't reconsider for many months. Trosper discussed, explained and negotiated in the meantime. To counter fears of brucellosis, he argued not all good buffalo come from Yellowstone. Bison at Wind Cave National Park near Hot Springs, S.D., have all the virtues of Yellowstone but none of the down side. Brucellosis hasn't been detected at Wind Cave since the 1980s. Trosper talked about starting small and working smart, good management practices to avoid disease in cattle and buffalo, about culture and ceremonies and tradition. On Oct. 2, the General Council reassessed what to do about buffalo. Harvey Spoonhunter, chairman of the Northern Arapaho Business Council, says there wasn't much discussion, let alone controversy. On an overwhelming vote, the General Council approved buffalo on Arapaho range and directed the Business Council to find a proper home for them. In a simple declaration, the tribe reaffirmed a dream. "I guess they know deep down inside what buffalo is to our people," Trosper says. "I guess that decision that happened, however it happened, whatever the reasons were, was the wrong decision for our tribe. To save what we have left, the buffalo has to be part."

Arapaho children at Ethete's Immersion School learn nouns first, matching words to pictures. Two preschoolers distract each other as Alvena Friday points to photos of cats and airplanes, soft drinks and bananas, even a National Geographic image of a blue-eyed Afghan girl. For each, she enunciates an Arapaho word. "Listen to the teacher," school director Alvena Oldman reproves a little girl, and then fixes on her friend. "You too." After all, this is serious business. The parents of these children -- or even their grandparents -- often don't speak Arapaho. While the children don't know it, they are being asked to save a culture. Today, the kids color and learn a word for buffalo. Three-year-old Anessa White hasn't grasped it yet. She covers her eyes, and then suddenly opens her fingers. "Peek-a-boo!" she exclaims. Anessa will catch on soon enough. Oldman says kids ages 3 to 5 learn the language quickly. But if Arapaho isn't spoken, at home or in schools, such knowledge will perish. "I'm glad I'm here on this earth," Arapaho children say back for their teacher. "I walk on this earth. I sing. On this earth I live." Language and buffalo are parts of the same life tree. One carries seeds of culture across time; the other provides a sturdy root. In 2006, the Arapaho Ranch accepted bison from the Medano-Zapata spread of southern Colorado. The small band was corralled, never intended for release. But one day, they busted out and headed for the hills. The ranch manager didn't believe the buffalo would last. Arapaho hunters had permission to shoot, but few seem inclined to do so. "I think they just love seeing them out there," David Stoner says. Last spring, a buffalo calf appeared, bringing the total to six since 2007. Unexpectedly, some old friends of the Northern Arapaho found their own way back, though they may not have survived this year's hunt. Jean Yellowbear, an Arapaho woman with a gentle voice and manner to match, tells with assurance where the buffalo have gone. "That's why you see that Milky Way in the sky. That's all the buffalo that went home." So maybe it stands to reason that each time a falling star lights up the night, a buffalo calf is born. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010

of Vicki Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010

of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

ETHETE

-- Dreams of buffalo have arisen on the Wind River Indian Reservation

of central Wyoming, reaching like long shadows down to the banks

of the Big Wind River.

ETHETE

-- Dreams of buffalo have arisen on the Wind River Indian Reservation

of central Wyoming, reaching like long shadows down to the banks

of the Big Wind River.