|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

May 1, 2010 - Volume

8 Number 5

|

||

|

|

||

|

Park Service, Crow

Tribe Interpret Past For Youth

|

||

|

by BRETT FRENCH of The

(Billings, MT) Gazette Staff

|

||

|

credits: photos by David

Grubbs of The (Billings, MT) Gazette Staff

|

|

Lodge Grass students tour sites of Fort C.F. Smith and Grapevine Creek battle FORT SMITH — In a pasture past a white mobile home with three bent satellite dishes drooping like faded gray sunflowers, a gravestone-sized marker has been erected in the fenced-off field.

"It's really interesting that anywhere else in America, this would be a really big site," said Col. Berris Samples, leader of the Lodge Grass Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps, on Tuesday. Samples brought his Crow students to the site as part of a daylong trip looking at two different historical sites — Fort C.F. Smith and the Grapevine Creek battle between Crow and Blackfeet Indians. Both are on the Crow Reservation. Working in concert with the Junior ROTC group, the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area's staff was able to access and interpret the sites for the students. Many parts of the reservation are closed to nonmembers of the tribe. "This is the first interpretive program ever given at the site of Fort C.F. Smith," said Chris Wilkinson, chief of interpretation for the Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area, a job he began just six months ago. He is also the first person to hold the job at the recreation area in at least 10 years.

"It's an opportunity for the Crow Tribe, if they want," Samples said. Wilkinson's talk to his young audience was short, covering the history of Fort C.F. Smith. The fort was established along the Bozeman Trail to protect wagon trains as they moved to Virginia City. Before it was built in 1864, an estimated 1,500 emigrants used the route. It was favored for making the trip to the gold mining town 450 miles shorter. But the Sioux saw the fort as an intrusion into their treasured hunting grounds. By 1866, raids on emigrant wagon trains by the Sioux as well as the Cheyenne had shut the trail down. To protect the emigrants, the U.S. Army decided to build forts along the route. Wilkinson called Fort C.F. Smith "the most remote and isolated of the three posts along the trail." Although the structure was only manned from 1866 to 1868, during those two years it was a flash point of conflict between the Sioux and the Army. But it also marked one of the first cooperative efforts between the Army and members of the Crow Tribe. "Your ancestors, the Crow Nation, were stuck in the middle of this," Wilkinson told the JROTC students. Without the help of Crow Indians acting as scouts, mail carriers and providing food to starving soldiers in the winter of 1867, Fort C.F. Smith might not have lasted two years. "I do not believe there is any greater example of hospitality to the U.S. Army," Wilkinson said. "Why do I tell you this today?" he asked rhetorically. "By celebrating your legacy, you are following in your ancestors' footsteps and extending hospitality. We thank you for allowing us to visit your sites." The students then loaded onto their bus, went back to the Park Service's contact station where they presented a diorama they had created of the Grapevine Creek battle to recreation area Supervisor Jerry Case. Then the entourage caravanned northwest into a remote field, site of the battle.

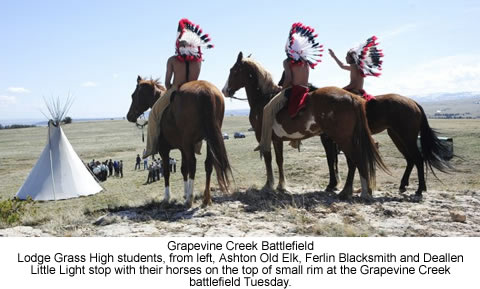

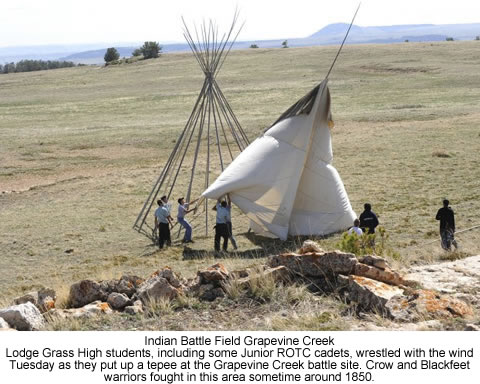

Arriving at the battle site, Ashton Old Elk, Dustin Kruger and Ferlin Blacksmith put bridles on the horses, jumped on bareback and tore across the wide pastures, working the horses into a lather. As a steady wind out of the north bowed the dry stalks of last year's prairie grass and meadowlarks trilled in the distance, Tim Spotted Horse went methodically and quietly about setting up the Crow canvas tepee in keeping with centuries-old traditions.

Surrounded and far from home, the Blackfeet had constructed 23 rock breastworks a few feet high to protect themselves as they fought off the more numerous Crow warriors. In the end, the rocks weren't protection enough. The Blackfeet managed to turn back the first few assaults, but in they end they were overrun. All but one or two of the Blackfeet were killed. The day's successful combat was due in large part to the bravery of Stump Horn, a Crow medicine man, according to the tribe's oral history.

Park Service archaeologist Chris Finley then talked to the JROTC students about how the area had been a migration route for humans for at least 10,000 years. Bison had long roamed these foothills, he said, providing food for tribal people. "For the Crow people, this was the heart of their home," he said. Three female JROTC students wearing ceremonial elk-tooth dresses then emerged from the school's bus. Together with the now-shirtless horseback riders — Old Elk, Blacksmith and Deallen Little Light — wearing leather pants and headdresses, the students posed in front of the tepee for photographs. Some wore green Army dress uniforms with shiny black dress shoes. Standing away from the hubbub, Theo Hugs smiled. She worked for the Bighorn Canyon NRA for 38 years, retiring just last year. She said the interaction between the tribe and the National Park Service is long overdue. "I think the kids need to know their heritage," she said. |

|

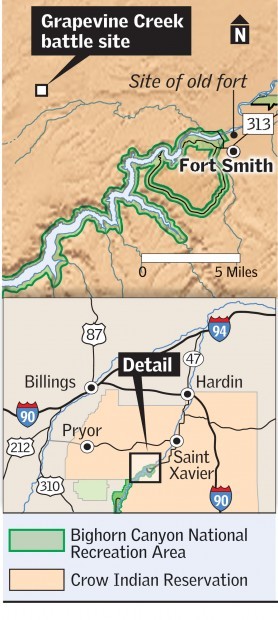

insert map here

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010

of Vicki Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010

of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Dedicated

in 1933, the stone and metal marker denotes the middle of what was

once Fort C.F. Smith, an isolated outpost built by the U.S. Army

to protect travelers on the Bozeman Trail to the gold camps of Virginia

City. Now, only humps in the dandelion-spotted terrain mark the

outer walls of the post, built on a bluff overlooking the Bighorn

River.

Dedicated

in 1933, the stone and metal marker denotes the middle of what was

once Fort C.F. Smith, an isolated outpost built by the U.S. Army

to protect travelers on the Bozeman Trail to the gold camps of Virginia

City. Now, only humps in the dandelion-spotted terrain mark the

outer walls of the post, built on a bluff overlooking the Bighorn

River. Members

of the recreation area's staff are hoping Tuesday's events are the

beginning of a mutually beneficial relationship between the tribe

and the National Park Service, although the details are still being

worked out.

Members

of the recreation area's staff are hoping Tuesday's events are the

beginning of a mutually beneficial relationship between the tribe

and the National Park Service, although the details are still being

worked out. Battle

site

Battle

site Just

behind him, on a small rise rimmed on three sides by white limestone

speckled with orange lichen, his ancestors 160 years ago nearly

wiped out a rival band of about 35 Blackfeet warriors. The incident,

about 10 miles north of Bighorn Canyon on the Crow Reservation,

is now known as the Grapevine Creek battle.

Just

behind him, on a small rise rimmed on three sides by white limestone

speckled with orange lichen, his ancestors 160 years ago nearly

wiped out a rival band of about 35 Blackfeet warriors. The incident,

about 10 miles north of Bighorn Canyon on the Crow Reservation,

is now known as the Grapevine Creek battle. Living

history

Living

history