|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

February 1, 2010 - Volume

8 Number 2

|

||

|

|

||

|

Preserving Cultural

Knowledge

|

||

|

by Amy Fletcher - Juneau

(AK) Empire

|

||

|

credits: All images courtesy

of Mark Kelley and the Sealaska Heritage Institute

|

|

Tlingit carver Rick Beasley releases step-by-step guides to a traditional art form A new series of books on traditional Tlingit carving offers an innovative approach to learning the art, by providing a detailed description of the techniques in printed form.

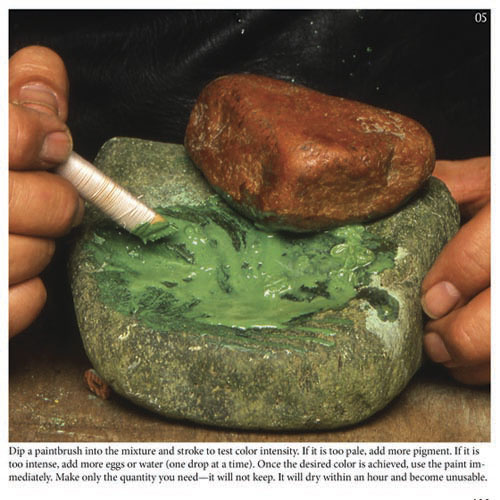

The three books, "How to Carve a Tlingit Tray," "How to Carve a Tlingit Hat" and "How to Carve a Tlingit Mask," are narrated by local carver Richard Beasley. Through a combination of step-by-step photos and text, Beasley breaks the often quite technical processes down into small, clear and manageable pieces. "This will take a person through from the very beginning to the very end," he said. "It's kind of like a road map or a blueprint." Though teaching Native carving through a print product is an innovative approach, the techniques Beasley outlines in the series are very traditional, drawing on knowledge passed from generation to generation, extending back thousands of years. "(In the books) we teach how to paint, how to make the paint with the minerals and rocks and dog salmon eggs," he said. "We teach how to inlay abalone and operculum (little white shells shaped like a lima bean). These are all methods that were used since before time we can record." Each of the three books contains sections on tools, paint, paintbrushes and inlay techniques, so artists can use one of the three volumes independently of the others.

"It's part of an idea that I want to leave my knowledge in print to others that it will be most beneficial to, mainly tribal members," Beasley said. A general introduction by SHI President Rosita Worl places Tlingit carving in its historical context and explains how a tradition that had existed for millennia was disrupted upon Native contact with Europeans. The apprenticeship system was weakened, she writes, but the art was kept alive. Artists such as Beasley play a critical role in the continued strength and survival of the culture, she writes. Each individual project is also introduced with an essay by Kathy Miller, former SHI ethnologist, who provides an overview of the significance of the items throughout history. The textual descriptions of how to complete the projects are matched with photographer Mark Kelley's vibrant color images of the artist at work. Kelley was an easy choice, Beasley said. "The photography is the most important part, and initially that's who I had in mind from the very beginning," Beasley said. "I just like the story his photos portray. He doesn't just document an image, he tells a story through his visual capabilities." Kathy Dye, director of media and publications at SHI, edited and designed the book. She said the texts are structured so that even beginners can use them. "One of our goals was for someone with no experience to pick up the books and learn the technique," she said. Dye sat by Beasley as he worked in the studio taking notes, as Kelley documented each step with his camera. After the photos were printed, Dye and Beasley went through them, put them in chronological order and then worked through the language for the captions to represent exactly what was happening in the frame. In some cases, the pair worked out additional cues to make the steps as clear as possible, such as adding letters and arrows to individual images that indicate specific spots on the wood, or show the direction of a carving stroke. Dye embarked on one of the projects herself to be sure the instructions were clear. "After we had the instructions roughed out, I did go through the tray project just to make sure I could do it," Dye said. "I figured if I could do it, anyone could do it." Dye said she was successful in following the directions, and that her appreciation for Native art was deepened after watching Beasley at work, an experience she described as a privilege.

"You'd get your wood and everything at school - your designs and your technical help - you'd carve at school and then take it home and carve at home," he said. "It's the kind of thing you'd just want to do. You could stay up until 2 in the morning carving up in your bedroom." The drive to carve also was fed by the inactivity of the long Juneau winters, he said. "A long time ago in Juneau there wasn't a darn thing to do here," he said. "The radios went off at midnight, there would be big snowbanks all they way up until April. And we'd carve like mad." There may not be as many group settings available to today's young artists, and the apprenticeship system may be less active than it once was, but there is no shortage of skill in Southeast, Beasley said. "There's a lot of talent out there, a lot of talent," he said. For carvers, the tray is the easiest of the three projects to make, Beasley said, followed by the hat and then the more difficult mask. The tray involves 69 steps, the hat 107, and the mask 310. One thing the books do not attempt to cover is the issue of design, something Beasley said would entail a whole separate volume. Instead, the series focuses on the technical and artistic specifications and techniques for producing each item, many of which are determined by the rules set down by tradition. Avoiding common mistakes was another reason Beasley was inspired to pursue the books project. "I don't want people having to fight to figure stuff out, or listen to people's suggestions that may not be right, go down dead alleys and all that," Beasley said. For example, Beasley said that when he was a student, he was instructed to carve a 4-inch ladle out of a huge block of wood. Later he learned that using a big chunk of wood to create a small item is not only time consuming, he said, but also disregards the nature of the wood itself. "The best wood to carve is the outer inch of the wood, that's where it's the densest, the freshest, the liveliest. So when you use these big pieces of wood, you end up using the wood that's inside of the tree that's not the best." One of the best local sources for fresh wood is Basin Road, he said, adding that local wood is ideal for the projects he describes because of its tight grain, the result of having growing up slowly in a cold environment. Beasley said he hopes to continue the "how to" series of art books. He is currently working on one on beading, and may include one metal work, the discipline he studied in college. Accomplished in all the Native arts, Beasley said documenting his knowledge has so far been very rewarding. "I loved it. Just absolutely loved it. Because I kind of think we're all responsible for passing on our knowledge and not letting it die with us. We're at that point in life." |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010

of Vicki Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010

of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Traditionally,

the cultural knowledge inherent in the creation of the artwork has

been passed down through master-apprentice relationships and workshops,

and the books' introduction makes clear this is still the best way

to learn. But for those without access to a teacher or a class,

and for those who live outside Southeast Alaska, the series offers

a way in.

Traditionally,

the cultural knowledge inherent in the creation of the artwork has

been passed down through master-apprentice relationships and workshops,

and the books' introduction makes clear this is still the best way

to learn. But for those without access to a teacher or a class,

and for those who live outside Southeast Alaska, the series offers

a way in.  In

documenting Beasley's expertise, the books, produced through Sealaska

Heritage Foundation and made possible through a federal grant from

the Administration for Native Americans, offer more than a "how

to" series for artists. They also provide a visual record of

Tlingit cultural knowledge for current and future generations.

In

documenting Beasley's expertise, the books, produced through Sealaska

Heritage Foundation and made possible through a federal grant from

the Administration for Native Americans, offer more than a "how

to" series for artists. They also provide a visual record of

Tlingit cultural knowledge for current and future generations.  Beasley,

who is a Raven of the Coho clan, is a lifelong carver who apprenticed

under many prominent Native artists. He said that when he was growing

up in Juneau, everybody carved. The art also was integrated into

the school system.

Beasley,

who is a Raven of the Coho clan, is a lifelong carver who apprenticed

under many prominent Native artists. He said that when he was growing

up in Juneau, everybody carved. The art also was integrated into

the school system.