|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

January 1, 2010 - Volume

8 Number 1

|

||

|

|

||

|

Walking Into the

Earth's Heart: The Grand Canyon

|

||

|

by Henry Shukman for

The New York Times

|

||

|

credits: Photos by Richard

Perry - The New York Times

|

|

“I

HAVE heard rumors of visitors who were disappointed,” J. B.

Priestley once said of the Grand Canyon. “The same people will

be disappointed at the Day of Judgment.”

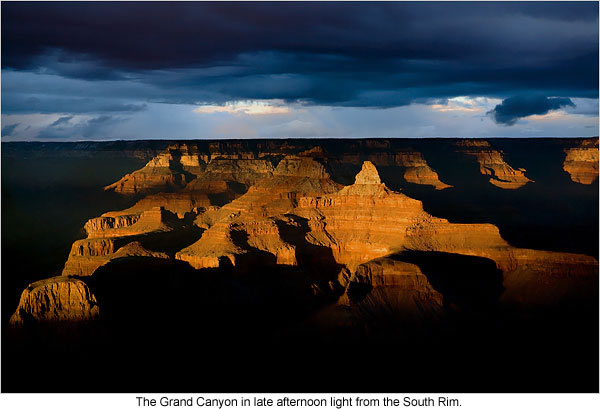

At this magnitude, scale is deceptive. Pedro de Castañeda, a Spaniard on the Coronado expedition of 1540, whose members were among the first Europeans ever to see the canyon, reported that a group of them scrambled some way down, and found that boulders they’d seen from the rim were not as they’d thought, the height of a man, but “taller than the great tower in Seville” (presumably the Giralda Tower, more than 300 feet high). We only stayed an hour or two. But before we left, from the rim I saw a trail, pale as chalk, winding down a huge slope beneath a cliff. There’s something about a trail seen from far away. That thread snaking over the landscape — where does it go, who uses it, why does it seem so intimate with the land? And why does it arouse such an intense longing to follow it? An unknown path seems almost necessarily a metaphor. We like to conceive of life as a thread, after all, a path crossing unexpected terrain on its journey to another element. When the trail winds across empty desert, up and down huge hillsides — as in the Grand Canyon — it’s all the more insistently allegorical. There wasn’t time to follow it, and I left with a nagging sense of opportunity lost, and that pale thread of a path still pulling at me.

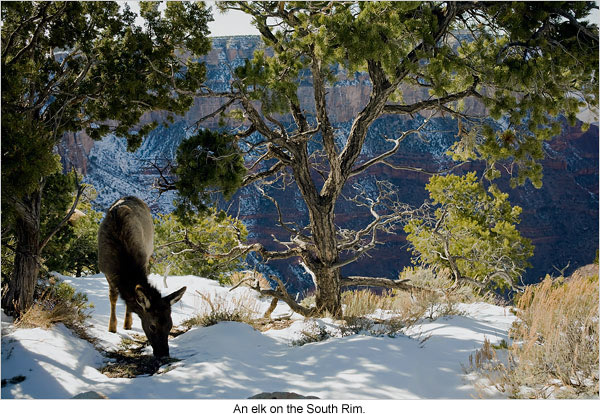

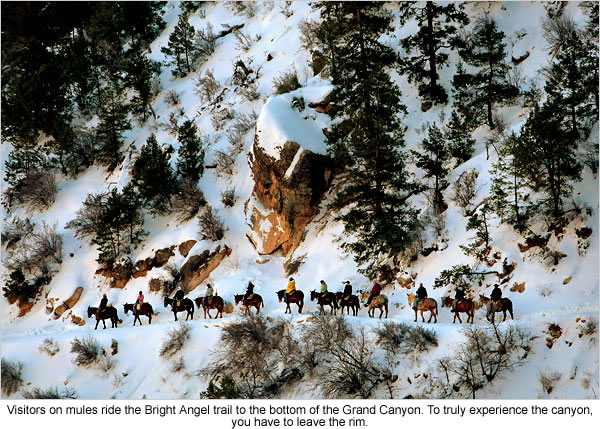

Winter is cool, and cool is good for hiking. To sweat actually uses energy. It’s true there’s snow on the trails, and long-molded tongues of ice pounded into enamel-like smoothness by the mules that go up and down with supplies, but that’s only on the highest reaches. Drop 2,000 feet from the rim and you’ll most likely be free of it. Sunlight becomes a blessing instead of a 120-degree curse, when you step out of chill shade into some welcome warmth. To experience the canyon, you have to leave the rim. The frustration aroused by the bigness, the grandness, on a rim-only visit becomes a liberation once you drop down. The modern world falls away. It’s not just a trip out of the human realm, but into the deep geology of the earth. Layer upon layer of the planet’s crust is revealed, stratum by stratum: the Toroweap limestone, the Coconino sandstone, the Redwall limestone, the Tonto Group; the Vishnu schist deep down, close to two billion years old, nearly half the total age of the planet — the stuff that is under our very feet as we go about our lives is laid bare here. And in the silence and stillness, in the solitude of the canyon in winter, it’s all the more impressive. Teddy Roosevelt said that all Americans should try to see it. He also declared, “We have gotten past the stage, my fellow-citizens, when we are to be pardoned if we treat any part of our country as something to be skinned.” Alas, he had no idea what was coming. But the Grand Canyon has not yet been skinned. Though not for want of trying.

This was all very well, but the canyon is one mile deep, and the trail itself about 10 miles long, and that translates to a very arduous walk, especially for an 8-year-old. By some arcane family algebra, it was Saul, our younger son, who was due a trip with me. After an impossibly smooth two-hour ride in the vintage coaches of the Grand Canyon Railway from the town of Williams, Ariz., the nearest major settlement south of the canyon, we checked in at Bright Angel Lodge near the canyon rim, to reconfirm our bookings for Phantom Ranch, down in the bottom. The woman behind the desk glanced at my young son and said: “I hope you’re planning to leave immediately, if not sooner.” It was already 1 o’clock, and most hikers set off in the morning.

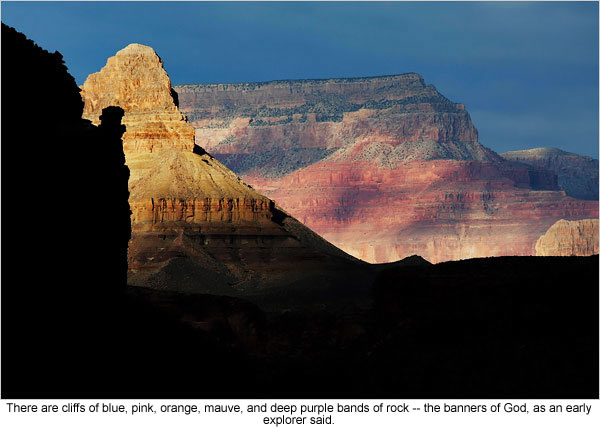

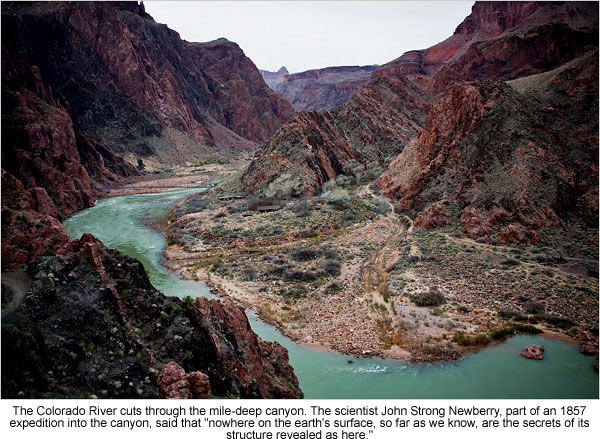

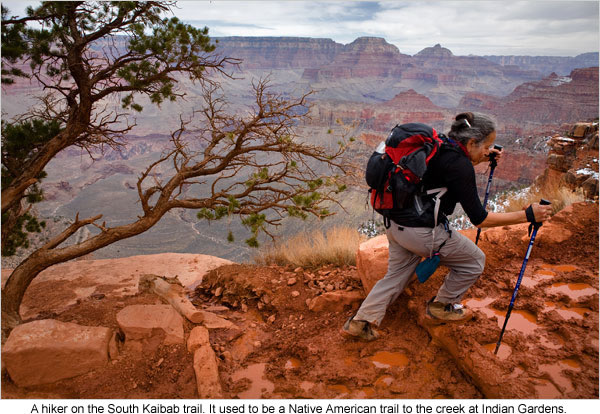

The fear only amplified over the first spectacular mile of trail, where we had to pick our way precariously over ice. But then we were out on the spine of a ridge, the aptly nicknamed Ooh-Aah Point, that dropped precipitately to either side, and the ice was all melted away. Here, it wasn’t so much about looking at a view as being in the midst of one. As we were gazing around us, two condors came gliding right over, so close we could hear the wind ruffling their feathers. “Keep in the middle,” I implored Saul, as he took to scampering along the parapet of rocks. Kids apparently can’t resist a parapet, no matter the drop beyond it. I wouldn’t want a creationist to misinterpret this, but I always find geology more or less unbelievable. Were these hundreds of square miles of limestone hundreds of feet deep truly made by trillions of marine creatures dying? Could a river really carve out a gash this deep? But before the construction of the Glen Canyon Dam, in a single day the Colorado River used to carry away 380,000 tons or more of silt, enough to fill a train 25 miles long. Each day. A river this size is indeed an efficient grinding tool. Below us, sweeping brown plateaus bulge as if they were soft upholstery. There are cliffs of blue, pink, orange, mauve, and deep purple bands of rock — the banners of God, as an early explorer said. True enough, the stark minerality of the desert always seems to rouse the inner mystic. The scientist John Strong Newberry, part of an 1857 expedition into the canyon, said that “nowhere on the earth’s surface, so far as we know, are the secrets of its structure revealed as here.” After the cliffs of pale Coconino limestone, we descend the Redwall limestone, into a deep tub of crimson stone. Finally at Skeleton Point we catch the first glimpse of the river, thousands of feet below us, announced by a distant roar. A vast sweep of shadow is coming off the rim above, spreading over the Tonto plateau. We plunge in and out of the shade on the switchbacks. So far, we have seen just four people.

Around 4 p.m., when we’ve descended some 4,000 feet, deep in the echoing inner canyon, amid runnels and gullies of deep shadow, beneath shoulders of shale and scree, Saul gets a kind of oxygen narcosis, skipping around, giggling, singing “Blue-blue-blue-blue” from “Austin Powers,” while my left knee goes supersonic, screeching at me to just please take one pace up instead of down. Enough with the down. Then Saul discovers the echo deep in the billion-year-old rock. “Go away, echo!” he shouts vainly, again and again. Endless new levels, new shears, shelves and tables to descend. Then all of a sudden, there the bridge is again. This time, we can see its individual railings, and as we approach, through a tunnel hewn straight through the rock, the thick, deep air beside the rushing river is like a balm. Whether it’s the late afternoon light, the fatigue, the pain in my knee, or the relief of getting down, I find myself wallowing in a wonderful endorphin bath. The world goes glassy. The canyon cliffs and trapezoids and pinnacles of rock all become resonant. I watch myself walk, as if the real me were a deep witness to my life, rather than the one who apparently lives it.

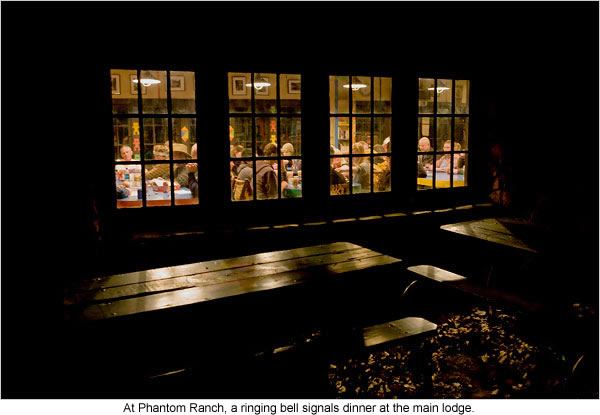

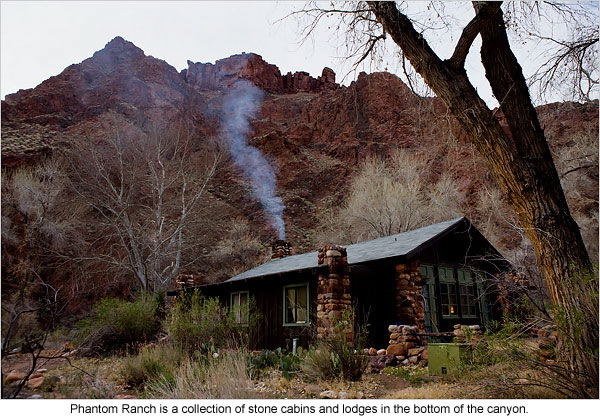

By the time we reach Phantom Ranch, its own side canyon, Bright Angel Creek, is deep in chilly shade. To reach the quiet huddle of stone and timber cabins under their grove of silvery cottonwoods, the trees tattered with old dry leaves, with a bunk waiting, and hot showers in the bathhouse, and the creek plashing by — relief floods in. But even though we’ve descended to 2,000 feet above sea level, it’s still freezing. When the ranch bell rings for dinner, some two dozen guests troop from the cabins through the frigid dusk to the main lodge, where we quietly feast on stew, corn bread and salad. We’re from all over, all walks of life: a student from Quebec, a trucker from Kentucky, a fisherman from Alaska, a college student from New York, a woman in insurance, from Pennsylvania. All these trappings of people’s lives seem to fade in the context of this deep retreat from the world. We’re just people, making the pilgrimage from cradle to grave. At 8 p.m. the dining room turns into a kind of mess hall. People sit around playing cards, or Trivial Pursuit, drinking wine or beer, and the counter opens for the sale of odds and ends. On a shelf sits the box for river mail, where letters wait for rafters coming downstream.

At first light Bright Angel Creek is chalky, vague. Then distant bluffs of red stone get picked out by the sun, and more and more bright geometries emerge. While I’m wondering what to do, rows of Easter Islandesque monoliths along the top of a cliff turn bright, and when the early sun strikes the high outcrops, I can see how they got their Egyptian and Hindi names. They do indeed look like sphinxes and Oriental temples. At 8 a.m. I go to the lodge and ask if they have a thermometer. They radio down to the nearby ranger station, and 10 minutes later Eston Littleboy Jones, a tall ranger equipped with a holstered automatic pistol and a Taser gun, tends to my son. Saul’s eyes light up at the sight of the guns. A quick checkup, and he’s bouncing back. By 10 he’s once again climbing from bunk to bunk, urging me to join in, and by 11 he’s insisting we walk the Overlook Trail mentioned by Eston, one and a half miles up to an outcrop overhanging the creek, then the River Loop Trail. Apparently, it was a swift-moving stomach bug. My legs are stiff as stilts. It’s as if never having been near a Stairmaster, I decided to spend all of yesterday on one. But homeopathically, hiking seems to ease them.

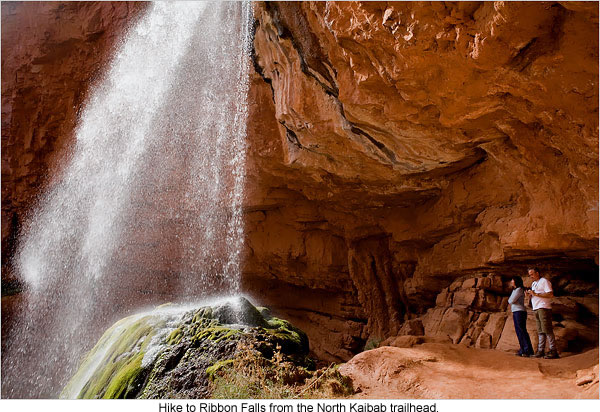

The next day we make the climb back up the Bright Angel Trail. Like the Kaibab Trail, this was also built for mules, having first been a Native American trail to the creek at Indian Gardens, halfway up. Mule trails are good for hikers. The beasts won’t put up with anything too steep. The trail makes its way up cliffs in endless switchbacks. Rows of flying buttresses, a soaring ship’s prow throwing a huge flag of shadow across a cliff, a forbidding wall of masonry half a mile above us: the views never stop coming. Way above, on the whitish cliffs just under the rim, something is winking. Could it be the windows of El Tovar, the old hotel where we’ll be spending the night? Along the climb at Devil’s Corkscrew, a chain of little waterfalls has carved out smooth dark basins in the rock. Again and again it strikes me how perfect the temperature is for hiking. Through a grove of willow the brilliant stream flashes by, icy cold. On that day we pass five hikers in all. Once again, it’s just us and the canyon. And the circling condors high overhead.

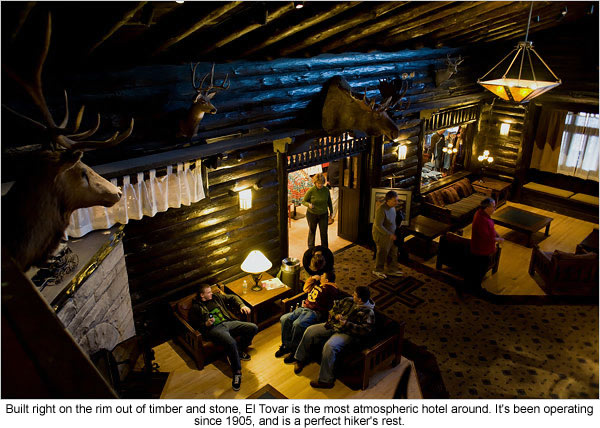

Finally we slump into El Tovar, the oldest Grand Canyon hotel, with its fireplaces of stone blocks and masses of dark timber, a perfect hiker’s rest. The truth is, when I pulled briefly into the Grand Canyon years before, I didn’t even truly comprehend that it was a canyon. It was such a vast landscape it seemed it might go on in pinnacles and gulfs for hundreds of miles. But once you’ve been down into it, you know what it is. You understand. At least a little. And the mere thought of being disappointed by it? I’m positively looking forward to Judgment Day.

WHERE THE VIEWS NEVER STOP COMING GETTING THERE We drove along Interstate 40 to Williams, Ariz., spent a night in the Grand Canyon Railway Hotel, left the car there and then took the Grand Canyon Railway (www.thetrain.com) to the canyon in the morning. The train leaves Williams once a day at 9:30 a.m.; the return train leaves at 3:30 p.m. daily. If that schedule doesn’t work for you, you can hire a taxi for the return trip, at around $120. A round-trip ticket on the train begins at $70 for an adult, $40 for a child. The National Park Service’s Web site (www.nps.gov/grca) is very helpful in planning a visit, as is www.grandcanyonlodges.com.

WHERE TO STAY El Tovar (888-297-2757; www.grandcanyonlodges.com) is the most atmospheric hotel around. Built right on the rim out of timber and stone and open since 1905, it shouldn’t be missed, provided the budget can stretch to it. A standard double room is currently $174. Phantom Ranch (888-297-2757; www.grandcanyonlodges.com) is a magical collection of stone cabins and lodges built in the bottom of the canyon, by Mary Colter. Dorm beds are about $42. The Grand Canyon Railway Hotel (233 North Grand Canyon Boulevard, Williams, Ariz.; 800-843-8724; www.thetrain.com) is not quite the atmospheric old railway edifice I’d imagined, but this is a comfortable, modern hotel. Doubles start at $169. Bright Angel Lodge (888-297-2757; www.grandcanyonlodges.com) is another old timber warren, built in 1935 and still full of charm. A standard room with bath is $90; a cabin on the canyon rim is $142.

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010

of Vicki Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010

of Paul C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

I

have to confess I was disappointed on my first visit to the canyon

more than a decade ago. One July, on our way to Los Angeles, my

family and I swung off the highway and made the 60-mile detour to

the South Rim, and found ourselves caught in a long traffic jam.

When we eventually managed to park, and walked to the rim, the scale

of the sight off the edge was so great it was hard to muster a response.

It was so vast, and so familiar from innumerable pictures, it might

just as well have been a picture. What impressed me most was the

Babel of languages audible among the files of visitors pouring off

the tour buses. It sounded like Times Square on a Saturday night,

with every continent represented in the hubbub.

I

have to confess I was disappointed on my first visit to the canyon

more than a decade ago. One July, on our way to Los Angeles, my

family and I swung off the highway and made the 60-mile detour to

the South Rim, and found ourselves caught in a long traffic jam.

When we eventually managed to park, and walked to the rim, the scale

of the sight off the edge was so great it was hard to muster a response.

It was so vast, and so familiar from innumerable pictures, it might

just as well have been a picture. What impressed me most was the

Babel of languages audible among the files of visitors pouring off

the tour buses. It sounded like Times Square on a Saturday night,

with every continent represented in the hubbub.  It

wasn’t until last winter that I got to answer that pull. And

the first thing I learned is that for the Grand Canyon, winter is

the time to go. As the chief district ranger John Evans told me,

“You’ll more or less have the place to yourself.”

Although the canyon is a desert, it’s a kind of oasis in winter

— a place of peace, sequestered from the rest of the world.

In three days of hiking I saw only two or three mule trains, each

carrying baggage not riders, and maybe two dozen hikers in all.

It

wasn’t until last winter that I got to answer that pull. And

the first thing I learned is that for the Grand Canyon, winter is

the time to go. As the chief district ranger John Evans told me,

“You’ll more or less have the place to yourself.”

Although the canyon is a desert, it’s a kind of oasis in winter

— a place of peace, sequestered from the rest of the world.

In three days of hiking I saw only two or three mule trains, each

carrying baggage not riders, and maybe two dozen hikers in all. As

I prepared to go, and talked to friends about the coming trip, I

was amazed how many people knew the inner canyon well. One acquaintance

told me that he had spent 300 nights below the rim, falling just

short of a lifetime’s ambition of a full year. In a grocery

store in Santa Fe, where I live, I got talking with a Grand Canyon-crazy

runner who hikes from rim to rim in a single day several times a

year. A woman in a coffee shop line told me about the time a 10-pound

falling rock nearly knocked her off a trail. I began to get the

feeling the Grand Canyon is truly a national monument, analogous

to the Lake District in England in its centrality to the nation’s

psyche. “Each man sees himself in the Grand Canyon,” Carl

Sandburg said. It’s something all Americans share, and can

take pride in.

As

I prepared to go, and talked to friends about the coming trip, I

was amazed how many people knew the inner canyon well. One acquaintance

told me that he had spent 300 nights below the rim, falling just

short of a lifetime’s ambition of a full year. In a grocery

store in Santa Fe, where I live, I got talking with a Grand Canyon-crazy

runner who hikes from rim to rim in a single day several times a

year. A woman in a coffee shop line told me about the time a 10-pound

falling rock nearly knocked her off a trail. I began to get the

feeling the Grand Canyon is truly a national monument, analogous

to the Lake District in England in its centrality to the nation’s

psyche. “Each man sees himself in the Grand Canyon,” Carl

Sandburg said. It’s something all Americans share, and can

take pride in. My

heart dropped. Saul is strong, fit as an Olympic athlete, indomitable

as a Gaul, but still only 8. Was it crazy and cruel to ask him to

walk down then up a whole mile of elevation? What if having got

him down he hurt himself, or his feisty spirit gave out? And then

there was my own bipedal apparatus. What if my own legs failed me?

My

heart dropped. Saul is strong, fit as an Olympic athlete, indomitable

as a Gaul, but still only 8. Was it crazy and cruel to ask him to

walk down then up a whole mile of elevation? What if having got

him down he hurt himself, or his feisty spirit gave out? And then

there was my own bipedal apparatus. What if my own legs failed me?

Then

just after Tipoff Point, the path brings us to another dizzying

corner, overlooking an ancient rusty amphitheater of Tonto Group

rock one way, while to the other, the air drops away to another

sight of the Colorado River far, far below, clay-red, rippling,

bloated. One of the two suspension bridges down there is visible

too. It all looks like a telephoto shot, the unfamiliar vertical

distance baffling the eye.

Then

just after Tipoff Point, the path brings us to another dizzying

corner, overlooking an ancient rusty amphitheater of Tonto Group

rock one way, while to the other, the air drops away to another

sight of the Colorado River far, far below, clay-red, rippling,

bloated. One of the two suspension bridges down there is visible

too. It all looks like a telephoto shot, the unfamiliar vertical

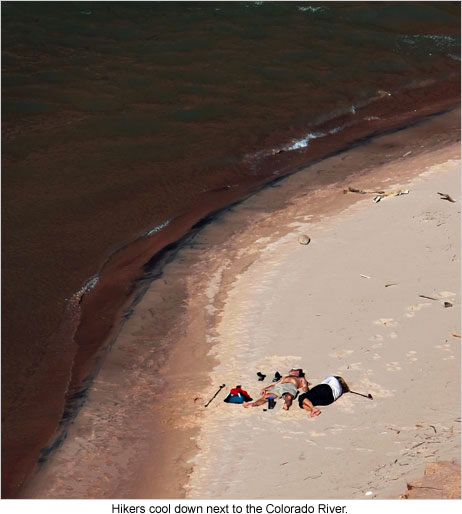

distance baffling the eye. Down

here, with the enormous Colorado River beside us, encased in the

immense walls of the inner gorge, we pass the old settlement of

Anasazi Indians who lived here 1,000 years ago. They planted corn

and squash, and used nothing that didn’t come from their immediate

surroundings. It occurs to me that today it takes a whole afternoon

on vertiginous trails to accomplish the reverse: to enter an environment

without human imports. This is surely the kind of immersion a hiker

seeks; this is why it feels like a pilgrimage to come here. It’s

good to reflect that if America has a heart, this just might be

it.

Down

here, with the enormous Colorado River beside us, encased in the

immense walls of the inner gorge, we pass the old settlement of

Anasazi Indians who lived here 1,000 years ago. They planted corn

and squash, and used nothing that didn’t come from their immediate

surroundings. It occurs to me that today it takes a whole afternoon

on vertiginous trails to accomplish the reverse: to enter an environment

without human imports. This is surely the kind of immersion a hiker

seeks; this is why it feels like a pilgrimage to come here. It’s

good to reflect that if America has a heart, this just might be

it. It

is 2 a.m. when a cry pierces the peace in our cabin: “I feel

sick, Daddy.” No sooner have I sprung from my bunk to fetch

the trash bin than Saul is hunched over it, retching. By 6 he is

hot with fever. It has happened: stuck at the apex of a mile-high

inverse mountain in winter, with a sick child.

It

is 2 a.m. when a cry pierces the peace in our cabin: “I feel

sick, Daddy.” No sooner have I sprung from my bunk to fetch

the trash bin than Saul is hunched over it, retching. By 6 he is

hot with fever. It has happened: stuck at the apex of a mile-high

inverse mountain in winter, with a sick child. From

one of the two suspension bridges we stare down at the river. “It

looks like they’re fighting a war,” Saul says of the white

waves. “Fighting to get up the river.” The frothing eddies

do seem to be struggling with the current. Two plumes of ripples

curve into one central stream like trails of smoke sucked into a

flue. The canyon walls create a constantly changing concertina effect

with volume. There’s a great bow of a pebble beach, except

the pebbles are the size of cars. It’s a landscape from “Lord

of the Rings,” with a perilous cliff path to match. Any minute

our way will be blocked by an orc.

From

one of the two suspension bridges we stare down at the river. “It

looks like they’re fighting a war,” Saul says of the white

waves. “Fighting to get up the river.” The frothing eddies

do seem to be struggling with the current. Two plumes of ripples

curve into one central stream like trails of smoke sucked into a

flue. The canyon walls create a constantly changing concertina effect

with volume. There’s a great bow of a pebble beach, except

the pebbles are the size of cars. It’s a landscape from “Lord

of the Rings,” with a perilous cliff path to match. Any minute

our way will be blocked by an orc. On

the last two miles, stalactites of milky ice hang beside the trail.

Then solid gray snow is underfoot, like lacquer, impregnated with

dust, slowing us right down. As we stand still waiting to see if

we can catch the sound of wind in the feathers of a condor gliding

by, we hear from up above the deep gurgle of the first motorbike.

Three days away from carbon culture, the modern world seems like

Thunderdome now.

On

the last two miles, stalactites of milky ice hang beside the trail.

Then solid gray snow is underfoot, like lacquer, impregnated with

dust, slowing us right down. As we stand still waiting to see if

we can catch the sound of wind in the feathers of a condor gliding

by, we hear from up above the deep gurgle of the first motorbike.

Three days away from carbon culture, the modern world seems like

Thunderdome now.