|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 12

|

||

|

|

||

|

OUTSIDE SHOT

|

||

|

by Carmen Renee Thompson

|

||

|

Basketball couldn't be further from Devon LeBeaux's mind as he stands amid a row of bare-chested Oglala Lakota Sioux men on South Dakota's Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Here in Thunder Valley, he is focused on the final stretch of the annual Sun Dance ceremony, a centuries-old, four-day ritual of fasting, praying, chanting and sweating. It's dusty and hot in the secluded clearing; temps on this June day have hit 100°. The men are barefoot, dressed only in ceremonial pants. LeBeaux is thirsty, hungry, sunburned and exhausted. But he stands there proudly, a red stripe painted across his nose and a sage crown with two black-and-white feathers atop his buzz cut. This is the fourth summer that LeBeaux has broken himself down to build up family and tribe. On cue, the brand new high school grad and other chosen singers belt out the closing chant, which includes the Lakota word for thanks: Pilamayelo. This year, the ceremony has been notably rigorous. Two days earlier, with the endless Black Hills and 140 members of his tribe as witnesses, the lanky six-footer underwent the voluntary sacrificial act called "hanging." His shoulder blades pierced with sharpened eagle bones attached to ropes, he was hoisted from a giant cottonwood tree, until his flesh ripped and broke him free. Later he, like the rest of the men, bore streams of dried blood on his back as a reminder of the offering. Full recovery usually takes several days. But that's time LeBeaux doesn't have.

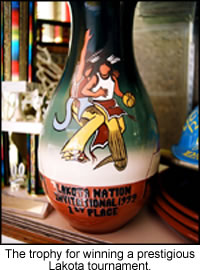

Between scrimmages, as Hornbeck's big German shepherd, LeBron, lounges courtside, the Regulators discuss how they might measure up against a stacked NABI field that includes highly rated teams like the Seminoles, from Florida, and the Apache Rez Runners, from Arizona. The guys from Pine Ridge have dominated their share of local rez tournaments and events in South Dakota, North Dakota and Colorado over the previous four years, but the NABI trophy has become the most prestigious hardware for a reservation, short of a state title—which usually requires a team to overcome predominantly white and wealthier schools and, in some cases, refs. LeBeaux's sun-darkened face brightens at the thought of being seen and recruited at NABI. He says the tourney is going to be fun because he's never been to Phoenix. But it's clear he's hoping it won't be the last time hoops takes him off the rez. The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, roughly the size of Connecticut, sits 110 miles south of Rapid City, S.D. Many of the 30,000 tribal members on the rez live in run-down trailers or small, one-story houses. Some are clustered, others are miles apart. It is a majestically beautiful, but isolated, place, with no movie theaters or malls. A new public transit system is just now getting off the ground. Although Pine Ridge is dry, kids learn early about Whiteclay, Neb., a "town," pop. 14, consisting primarily of liquor stores, just over the state line three miles away. Asked how prevalent drug and alcohol abuse is on the rez, LeBeaux turns somber. "It's pitiful," he says. "You see 5- and 10-year-olds smoking pot, getting junk, too. Meth and coke are the main reasons there are shootings." Just as poverty-stricken urban ghettos spawned graffiti, hip-hop and streetball as outlets for the anger and frustration housed within, so has the rural desolation of reservation living produced its own art form. Rezball—as Native Americans have dubbed it—is the most popular sport in Pine Ridge and on scores of reservations across the country. "Back when we were a great nation roaming the plains, people didn't make it unless they had physical ability," says Regulators head coach Dave Archambault, Hornbeck's grandfather. "You had to be strong enough to guide a horse into a buffalo herd using just your legs, so your arms were free to shoot a bow and arrow. Nowadays, there's nothing else on a reservation that comes as close to that physicality as basketball." The old Lakota paths to manhood are different from what they once were, but their imprint remains in the ways young men on the rez now search for respect. Here, LeBeaux seems to have an advantage, not just because he can play the revered sport of basketball but because he is the youngest son of legendary Pine Ridge coach Lyle "Dusty" LeBeaux. The senior LeBeaux won a state title in 1995 and has led all three rez high schools to the title game. Family bloodlines run deep on the rez. Many people know their forefathers all the way back to before the Lakota Sioux became a people interrupted. Reverence is high for the greatness of chiefs like Sitting Bull, Red Cloud and Crazy Horse, whose brave resistances to being put on reservations in the mid- and late-1800s included defeating Custer at Little Big Horn. Many, especially the young, embrace that warrior culture and try to update it. Not surprisingly, that means a strong affinity for hip-hop's street culture and ghetto glamorization.

And so they run. Rezball is a smashmouth game of speed, aggression and stamina. Full-court presses and man D are applied relentlessly, but the transition game is the game. Guards often start a break after receiving the inbounds pass; set plays are rare. Rezball makes the 2007 Suns look like the 1995 Knicks. Squads with three guys taller than 6'3" are rare, so even the short guys know how to play big, and all five positions boast guardlike handles and shooting skills. Watching the best teams will rivet you to your seat—from the way players improvise at warp speed to their sheer endurance and the dialed-in-but-carefree way they ball.

Some have had offers. Ask anybody which players from Pine Ridge were D1 good, maybe even NBA good, and they'll mention Jess Heart, a 6'4" USA Today honorable mention whom Kansas State recruited in 1999 (he chose a junior college but ultimately dropped out), or Willie White, whose academic struggles prevented his college career from taking off. But they aren't the only guys on the roll call of rez talents gone to waste. Being ill-prepared for school is a big obstacle between rezball players and the next level, and so is the culture shock that comes with trading the familiarity of rez life for the anonymity of the city—becoming the lone Native American in the dorm. And low retention rates cause some coaches to think twice about offering a chance in the first place. Just 33 Native American men and women played on D1 hoops teams in the 2005-06 season, out of roughly 9,800 athletes. (Native Americans account for 1.5% of the U.S. population). Before it leads to dreams of the NBA, basketball leads first and foremost to a chance to get more education and, hopefully, better jobs. But part of the problem is that many kids on the rez hate school. Hard to blame them. Some have to travel more than 50 miles each way. Then there's a feeling that the curriculum doesn't speak to them. But no school means no hoops, so those who want to play endure. It's hard to pass up those Friday Night Lights moments that have friends and neighbors coming out in droves to see the kings of the court. If not a king, LeBeaux is at least a prince. He's a decent shooter and a tenacious defensive pickpocket. That skill set plus his leadership qualities would make him a nice addition to most juco squads, for sure. Maybe even a D2 or D3 program, if he had the grades. But whatever comes next, he has to factor in the needs of Aiden, his 3-month-old son. Aiden's arrival helped distract Devon from the unbluntable trauma of the passing of his mom, Tess, 18 months earlier at age 50. "I went crazy and ran away," LeBeaux says softly. "I couldn't handle it." Too-early deaths are a reality all too common in Pine Ridge, where life expectancy is just 48 for men and 52 for women, in each case about 25 years shorter than in the rest of the country. If he could line it up, LeBeaux says, he'd take his son and girlfriend, Brittne, with him to school, get a house, play hoops—hopefully, on scholarship—and try to make it through. But after seeing the same cycle swallow countless other players on the rez, he knows it might be his turn. His high school basketball career is over, and he's got practically no shot left at turning his talent into a golden ticket. Job prospects are poor as ever in Pine Ridge; unemployment is over 80%. That's why the NABI tourney looms so large. The Regulators are one of a record 86 boys' and girls' teams from 16 states who have come to Phoenix to compete in the fifth annual NABI, in July. The tournament, sponsored by rezball admirers in the Phoenix Suns organization, has drawn the most media attention it has garnered yet in its quest to create exposure for the game and its top players. Weary from the travel—Hornbeck's mom, Billie, drove a van to Denver, where they caught a cheap flight—they get off to a slow start. A handful of family members wearing airbrushed Regulators T-shirts cheer urgently from the bleachers, finally coaxing a rally that brings their sons back from 14 points down. A dicey first win under their belts, the team shifts into high gear. A tear through the next few rounds includes the takedown of the Rez Runners. The tournament's early rounds are hosted at gyms on nearby reservations. LeBeaux and the others soak it all in, from the Navajo snacks sold at concession stands, to the Pow Wow drum music that alternates with hip-hop on the loudspeakers during timeouts, to the Native American fans of all ages who crowd around the bracket boards in the lobbies after games. In fact, the players are so engrossed by the sights and sounds that no one notices the paltry number of people wielding clipboards in the stands. Buzz about the upstart Regulators grows among coaches and fans as the team marches to the Final Four, a showdown in US Airways Center with the Oklahoma-based Cheyenne Arapaho squad. Before the game, in the visitors' locker room, LeBeaux leads the team in a chant and prayer to ready everyone for the clash. Out on the Suns' home floor, LeBeaux and Hornbeck wreak havoc with crafty steals and precision baseball passes for layups. The Regulators jump out to a 13-point halftime lead. But Cheyenne Arapaho prove too tall and too tough, banging underneath and hitting long-range threes. They go on to win this game and the next, taking the championship. The Regulators' disappointment at their surprising third-place finish is compounded by the belated realization that Scouts' Row was mostly empty until the end. When team and entourage return to Pine Ridge, Hornbeck's mom drops off each guy at his home. They say simply, "See ya later," not fully grasping that after playing together since elementary school, they've played their last game together as the Regulators. Basketball couldn't be further from Devon LeBeaux's mind as he stands in Thunder Valley, taking part in his fifth Sun Dance ceremony. The 2008 NABI is just weeks away, but he won't be going. The former Regulator's life has been full of challenges since his trip to Phoenix a year ago. Not long after he and his teammates came back from the tourney, he headed off to Killeen, Texas, to be with Brittne and Aiden, putting off enrolling in a local Indian college in the process. After a few months of looking for work and playing pickup ball, the arrangement unraveled, and, unable to make it right, he found himself alone back in Pine Ridge. LeBeaux played in weekend hoops tourneys around the rez, helped brother Jerome, took a construction job and wrote rap songs about his mom, son and life on the rez. This spring, he received an offer to coach basketball at local Porcupine Day School. Flattered, he still turned it down. "I want to coach, and I think I could be good at it," he says. "But I wasn't ready just yet." Some of his former teammates weren't ready to take the next step either. LeBeaux was bummed to hear that two of three Regulators who went to play at jucos dropped out. Now both are back. One got a job at the rehab center; the other is still looking.

If they do come back, the game will be waiting, a reason to run and sweat, another source of tribal spirit. LeBeaux sees his experience—and that of all the others who played rezball before him with no next level on the other side—as part of the sacrifice, part of the cycle that may one day produce a rezball player who can ride his game to college and beyond. All that wasted talent isn't wasted at all, LeBeaux says. Like the Sun Dance, there is honor in hardship endured for the benefit of others. |

|||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Paul

C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

It's

called Rezball—an amped-up style of hoops created on Reservations

and showcased in a huge all-native tourney. But when the games are

done, the stars are left wondering: how long will they get to shine?

It's

called Rezball—an amped-up style of hoops created on Reservations

and showcased in a huge all-native tourney. But when the games are

done, the stars are left wondering: how long will they get to shine? As

LeBeaux talks, his eyes follow his teammates as they go hard in

a heated scrimmage against older guys from around the rez. He cheers

as junior point guard Brice Hornbeck, a rabbit-quick and wily ballhandler,

conducts a lightning-swift rebound/outlet/thread-the-needle-in-traffic

bounce pass/layup sequence. "People like how I fire up the

team," LeBeaux says. "The guys are shy. I'm loud, and

it brings them out of their shells."

As

LeBeaux talks, his eyes follow his teammates as they go hard in

a heated scrimmage against older guys from around the rez. He cheers

as junior point guard Brice Hornbeck, a rabbit-quick and wily ballhandler,

conducts a lightning-swift rebound/outlet/thread-the-needle-in-traffic

bounce pass/layup sequence. "People like how I fire up the

team," LeBeaux says. "The guys are shy. I'm loud, and

it brings them out of their shells." The

game is all action, no filler, which is why fans pack local gyms

to see the powerhouse teams square off, and the top players get

their 15 minutes of fame as heroes, asked to sign autographs and

pose for pics after games. But 15 minutes is almost always all rezballers

get. "We've had a lot of talented players around here,"

says LeBeaux. "But they ended up stuck here and started using

drugs and stuff." Few scouts make the trip out to Pine Ridge.

"There's a lot of guys, who if good colleges had asked them

to come, I bet their lives would have been different."

The

game is all action, no filler, which is why fans pack local gyms

to see the powerhouse teams square off, and the top players get

their 15 minutes of fame as heroes, asked to sign autographs and

pose for pics after games. But 15 minutes is almost always all rezballers

get. "We've had a lot of talented players around here,"

says LeBeaux. "But they ended up stuck here and started using

drugs and stuff." Few scouts make the trip out to Pine Ridge.

"There's a lot of guys, who if good colleges had asked them

to come, I bet their lives would have been different."  So

hope remains. Red Cloud coach Rama is sending four of his seniors

to junior colleges this fall. That's more than in any of his previous

five years in the job. He says he's had some success in motivating

players to want more for themselves, to think about their futures.

But he knows how the revolving door works. Many kids go off to college,

almost as many come back. Awaiting the next turn is always his quiet

fear. "I try to give them the tools to handle pressures on

and off the court," says Rama. "After that I can just

hope for the best."

So

hope remains. Red Cloud coach Rama is sending four of his seniors

to junior colleges this fall. That's more than in any of his previous

five years in the job. He says he's had some success in motivating

players to want more for themselves, to think about their futures.

But he knows how the revolving door works. Many kids go off to college,

almost as many come back. Awaiting the next turn is always his quiet

fear. "I try to give them the tools to handle pressures on

and off the court," says Rama. "After that I can just

hope for the best."