|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 12

|

||

|

|

||

|

A Bridge To The Past

|

||

|

by Matt Durkee, The

(Crescent, CA) Daily Triplicate

|

||

|

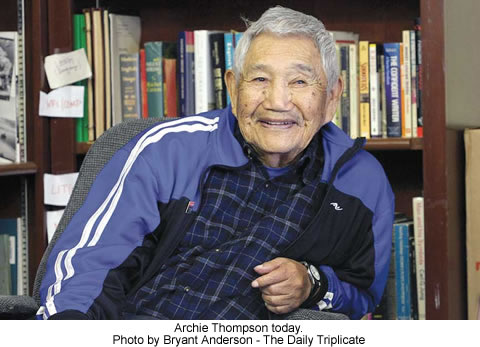

At age 90 he still aids youths with native language

"She didn't speak English, and I used to make fun of her all the time, but that's how I learned. She spoke to me every day," Thompson said. "I learned (Yurok) as I went along. She'd teach me as I went." For Thompson, the Yurok language is infused with memories of the sprawling Klamath ranch and the many Yuroks he met there. "We had a ranch with plenty to eat, and I remember all the old Indians used to come down there to eat, some for days or weeks or months, and we fed all of them, and we didn't cost them money, and we would talk. "Sometimes there would be nothing but old Indian people sitting around the stove talking Yurok, and I always remember that." Archie the boy would sit and listen to their entertaining conversations. "They all laughed and someone would tell a good story. It was all Indian talk, and they wouldn't talk no white talk at all." Many decades later, the 90-year-old Thompson is the elder Yurok who is passing on the language to a new generation. Twice a week, Thompson sits in on Yurok language classes for high-schoolers at Klamath River Early College of the Redwoods in Klamath, where he serves as a living resource, one of a handful of surviving fluent speakers.

Thompson participates in the national Foster Grandparent program, which is run locally by North Coast Opportunities, a regional non-profit. His work is so valuable that it has been recognized nationally — this year he traveled to Washington, D.C., to receive the Silver Honor in the Mentor Category from the MetLife Foundation and the National Association of Area Agencies on Aging. The trip was a special experience for Thompson. He hobnobbed with First District Congressman Mike Thompson, and he traveled to North Carolina to see his son, Archie Jr., a retired paratrooper with sons and grandsons of his own — Yurok men who speak with incongruous Southern accents. Thompson speaks of his son with evident pride. "He's got a big home back there. He's not hurting for nothing." SITTING

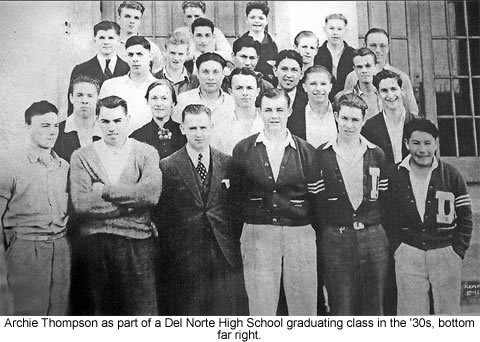

AND LISTENING TO YUROKS AS A CHILD "My mother married a white guy, and they didn't want me around, and they put me in the government school in Hoopa," he said. In that era, Native American children as young as 5 years old were routinely taken from their families by the federal government and placed in distant boarding schools where they were punished for speaking their native languages and forced to wear non-traditional clothing — military uniforms that they would drill and march in. Thompson lived for three years at the school, from age 5–8, and lost much of his knowledge of the Yurok language that was spoken to him as a young child in Wo-tek village where he was born. At 8, Thompson was taken out of the school and brought to his grandmother, Rosie Jack Happell, who had a 25-acre ranch in Klamath. It was a place where, as he puts it, he "excelled in everything." Archie learned how to milk his grandmother's cows and feed the pigs and chickens. Whenever he wasn't helping on the ranch, he was on the river fishing. "I used to dip candlefish all night. My boat would just be white on the bottom with fish, and my grandmother would come with a basket and she would put them in the smokehouse." Thompson spent the rest of his childhood living on the ranch, milking the cows morning and night and spending much of the rest of the time fishing on the river for salmon and eels to put in the smokehouse. "To me," he said, "that was the life. No one had to tell me what to do. I was my boss." Archie attended grammar school in Klamath, and then Del Norte High School in Crescent City, where he competed on the school's football, baseball, basketball and track teams, becoming the school's first Native American to letter in sports, he said. FORCED

BY TRAGEDY INTO SINGLE PARENTING After the war, Thompson returned to Klamath and worked for logging companies, in sawmills, in the woods, and rafting logs down the river. He married and fathered eight children, four boys and four girls, before his wife Elda died from a fall when their youngest was only 2. By virtue of a work mishap two years before that crushed his hip between two logs — Thompson regards it as providence — he had a disability pension that allowed him to stay home and raise his children by himself. "You can't work and raise them, no way. So I stayed home and cooked and washed clothes," he said. In a lengthy interview published in "The Original Patriots: Northern California Indian Veterans of World War Two" by Chag Lowry, Thompson said that he now has "a tribe of his own," with eight children, 25 grandchildren and 20 great-grandchildren. In fact, Thompson's later life has been punctuated with dedicated work building up the legacy of not only his familial tribe, but the greater Yurok tribe. In addition to his current work with high school students at Klamath River Early College of the Redwoods, he has taught Yurok language classes in Crescent City; he has helped with Yurok language projects at Humboldt State, and he has been an important source of knowledge for the Yurok Language Project at the University of California in Berkeley, a major effort to create an online digital archive of the Yurok language: dictionary, grammar, texts and language lessons. ‘SOMETHING

HANDED DOWN BY YOUR FOREFATHERS' "It's good to learn your own language! You should never lose it. It's something handed down by your forefathers. "They've been on this land for a long time; they know exactly what is happening. They know when the salmon go up the river; and the sturgeon and the eels. They know all these things." Even though Thompson doesn't always feel well, he is dedicated to making his twice weekly trips on Tuesdays and Thursdays from his home in Crescent City to the school in Klamath, where he sits with the students and helps with the lessons. "If I need to remember how to say something or I don't know how to say it, he will say it," explained language teacher Barbara McQuillen. "He's like a resource person for me in the class because Yurok was his first language. I have an English accent and will always have that. He will always have that first-language accent. It helps the students to hear him say it as opposed to hearing me say it." Thompson also helps the class in other ways, McQuillen said. "He's always willing to help with assignments. They will move next to him and he will help them whenever they need help. And he will help with classroom management. He likes to tell students the importance of paying attention and learning, not just in the language but in life." McQuillen said Thompson gets an impish kick out of of being the first to answer the teacher's questions. "And then I have to say, ‘OK, I know you know this,' and he laughs and thinks it's funny. And the very next question he'll be the very first to answer again, and the students after the first few classes learn he's going to get the answer and so they move closer to him so they can hear because he starts saying it quieter, only to them. But I think it shows he just loves the language and loves hearing them speak." KEEPING

A CULTURE'S FLAME ALIVE "A lot of kids don't have grandparents here in the community, so what they get from (foster grandparents) is respect. They learn to be gentle and kind and nice, to be careful: all of those things that come with fragile grandparents — and some of them aren't even so fragile," Yost said. As a teacher, McQuillen sees firsthand how foster grandparents make an impact on students. "For any of the foster grandparents that come into the program, the students make sure they have a good seat, a comfortable chair, that they're warm enough, have enough to eat at lunch, they get them a plate, put the heater next to them. I think they really think about the respect part of being elders and their place in the community," McQuillen said. Elders are especially important in the Yurok culture because they keep culture's flame alive and represent a bridge between the tribe's long past and an uncertain future. "They bring a different perspective for why we do things the way we do them," McQuillen said. Thompson's memory and experiences are especially important to the tribe, said tribal educational director Jim McQuillen, because Thompson lived in such a pivotal time for the Yurok. "He grew up in a generation that saw a lot of change for the American Indian community, where the language was changing to English. Living strictly from the land was changing and people were being moved off their traditional lands and pushed into other areas. So he's seen a lot of history in his 90 years." Thompson's humorous yet soft-spoken manner belies a wealth of information about the tribe's ancient ways, Jim McQuillen said. "He's got fantastic stories of his own childhood in this area, walking in the land and mountains here, hunting quail and ducks and geese and other things," Jim McQuillen explained. "Yuroks were known for their network of trails, and he has stories of that, so he captivates students with that information along with his knowledge of the language." Specifically in matters of the Yurok language, Thompson represents something particularly rare and special, according to Andrew Garrett, a linguistics professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Garrett is one of two language experts overseeing the Yurok Language Project, and he has recorded many native Yurok speakers over the years to compile a comprehensive record of its words, grammar and oral literature. "Like every language, there are local differences in the language," Garrett explains. "So It was great to work with Archie because there haven't been many we've worked with who speak the river mouth/coast accent version of Yurok. Archie's the only person I've worked with who talked like that." Over the years, Thompson has earned the respect and appreciation of many people within his family and his tribe. What he represents as an elder to his children, both literal and tribal, is worth far more than any "Silver Award" can convey. In his quiet laugh and ancient language are the whispers of thousands of his people who have lived and died, a priceless treasure of a nation determined to survive. "Guys like Archie are just making it happen," Jim McQuillen said. "Just leaving the gift behind for anyone who wants it." |

|

|

insert map here

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Paul

C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Archie

Thompson learned the Yurok language as a boy living on his grandmother's

ranch.

Archie

Thompson learned the Yurok language as a boy living on his grandmother's

ranch.  After

graduating from high school in the late '30s, Thompson went to Sherman

Indian School in Riverside, a place that taught manual labor skills

to many Native Americans from Northern California. There he learned

metal-working, welding and repair. He worked in Los Angeles shipyards

and was drafted into the Navy at the onset of World War II. Thompson

taught welding classes stateside and was then sent to the South

Pacific, where he spent the war repairing damaged ships.

After

graduating from high school in the late '30s, Thompson went to Sherman

Indian School in Riverside, a place that taught manual labor skills

to many Native Americans from Northern California. There he learned

metal-working, welding and repair. He worked in Los Angeles shipyards

and was drafted into the Navy at the onset of World War II. Thompson

taught welding classes stateside and was then sent to the South

Pacific, where he spent the war repairing damaged ships.