|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

November 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 11

|

||

|

|

||

|

Masks Reveal The

Maker's Inner Self

|

||

|

by Rosalie Robles Crowe

- Arizona Daily Star

|

||

|

credits: photos by James

Gregg - Arizona Daily Star

|

|

With no hesitation, he chooses a block of wood about 10 inches tall to carve into a Yoeme pascola mask, the kind for which he is becoming so well-known among art collectors. Pulling a machete from the ground, he begins to hack away pieces. Nearby are the other tools he'll use, all simple ones — a file or rasp, a chisel and a utility knife, the kind you use to open cardboard boxes. The carving goes quickly for him, in part because the wood — cottonwood, mostly — is soft. It's also because he already knows what he will carve when he chooses the wood, from the area around Empire Ranch southeast of Tucson. It's not a case of taking whatever he can find, however. Choosing the wood is, in itself, a prayer. "We ask the Creator (to guide us) when we take the wood," he says. "To me, the wood has to be special. It talks to me — it wants to be carved." But some wood is not to be. It doesn't want to become a mask, "so I leave it." The wood is cut into suitably sized blocks. Using the machete, he begins forming the head for the face he sees in the wood. With the file, he shapes the wood into an oval and smooths any rough edges. Then he uses the utility knife to form the features and the chisel for the eyeholes and mouth.

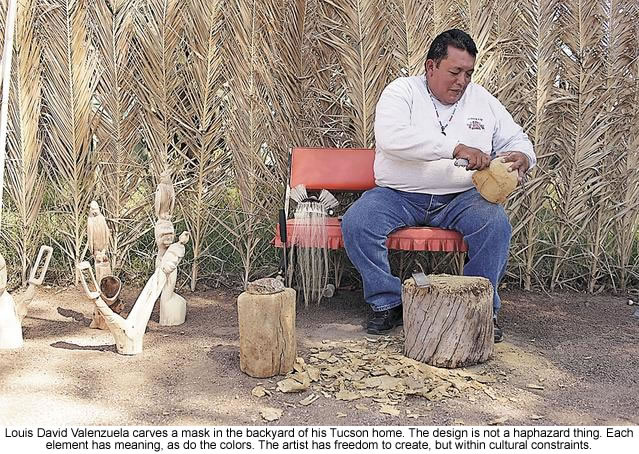

It is the painting that is time-consuming. The wood is sanded, and a base coat — usually black — is applied. Then comes the design in white and red, possibly other colors. But the design is not a haphazard thing. Each element has meaning, as do the colors. The artist has freedom to create, but within cultural constraints. You can see some of Valenzuela's masks, paintings and sculptures today at Tohono Chul Park's celebration of Yoeme art and culture.

The exhibit, "Yoeme Carving: Generations of Wooden Faces," also features art by several other Yoeme artists, including the celebrated Martinez family — Feliciana, Eddie and the late Frank and Frank Jr. Also, David Moreno and the late Mexican-American artist Arturo Montoya. Valenzuela carves masks for use in Yoeme ceremonies, and others for exhibit or art collectors only. The difference is that the ones he creates strictly as art are not "blessed," never intended for use by a pascola — "the old man of the fiesta." And while he does sell the masks he makes as art, he never charges for the masks a pascola uses. Those are for the pascola only and should not be touched by another person.

It was Montoya who taught him the basics: "to mix paints, to mix colors. He saw my talent when I was a kid," Valenzuela says. "He would give paintings to other kids who would help him, but he wouldn't give one to me, even though he picked me as his assistant. " 'Why?' I asked him. 'Because you are going to be a great artist,' he said." Valenzuela didn't begin to work with Acuña until he was 25. Acuña "would carve the mask, and I would design them with my art." "But I was curious, and I wanted to carve, too. He said, 'You can do it; just put your mind to it.' "The first mask that I carved looked like a Frankenstein," Valenzuela says. Then he starts laughing: "A woman bought it." Valenzuela, 46, has been doing art — painting and sculpture as well as mask carving — for about 36 years, but it has been only in the last several that he has begun to gain recognition. "Sometimes we take life for granted," Valenzuela says, recalling the many years when he drank. But five years ago his older brother, Christopher Gregory Valenzuela, was diagnosed with cancer. While he struggled with the disease, he asked his younger brother to promise to quit drinking. "I couldn't promise sobriety," Valenzuela says, because every past promise he made, he broke. Still, he said he'd quit. Today, he is sober and his art is flourishing and gaining recognition. He is taking a stronger part in his community and finding ways to reach out to others, particularly children who show an interest in art. He recalls the words of his friend and fellow artist, the late Leonard F. Chanda, who always urged him to give up drinking and to join him in an art show: " 'When you're ready, the way will open up for you,' he used to say," Valenzuela recalled. "He was right." These days, Valenzuela devotes much of his time to giving back to his community. He teaches art to children at Hohokam Elementary School during its end-of-the-year camping trip, and he's active in the Yaqui community. Contact reporter Rosalie Crowe at 573-4105 or rcrowe@azstarnet.com

|

|||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Paul

C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Louis

David Valenzuela is seated on an old kitchen chair in a favored

spot in his home art studio — a corner of his backyard shaded

by trees and screened for privacy with palm fronds woven through

the chain-link fence.

Louis

David Valenzuela is seated on an old kitchen chair in a favored

spot in his home art studio — a corner of his backyard shaded

by trees and screened for privacy with palm fronds woven through

the chain-link fence.

Valenzuela

began his art when he was 10, learning from Montoya, whom he calls

his mentor. He learned carving from Yoeme elder Jesus Acuña.

Valenzuela

began his art when he was 10, learning from Montoya, whom he calls

his mentor. He learned carving from Yoeme elder Jesus Acuña.