|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

September 1, 2009 -

Volume 7 Number 9

|

||

|

|

||

|

Stickball Workshop

Introduces Craft, Art Of Traditional Game

|

||

|

by Kelly Koepke - Indian

Country Today correspondent

|

||

|

As part of the center's ongoing exhibit "Celebrating Native Legacies: Works in Clay" by Kathleen Wall, Victor Wildcat journeyed from Muskogee, Okla. to share his knowledge and skill of this traditional game, considered the oldest sport in America. Wildcat, part of the Cherokee Savannah Clan with Creek and Natchez descent, has taught Cherokee cultural crafts for 15 years as a Title VII Native American instructor at Ft. Gibson Public Schools. He conducts stick making workshops and guides the games in the Cherokee language. "For the Cherokee, this is how we're trying to immerse the language into everyday life and increase language skills and vocabulary. I try to incorporate language into everything I teach." According to the Cherokee Heritage Center, stickball is an ancient game that southeastern American Indians called the "Little Brother of War" because it required many of the same skills and rituals as battle. It is considered the forerunner of modern lacrosse, and was historically a method to settle disputes between towns, and sometimes between tribes. The modern objective of stickball is to score points by handling a ball with a pair of sticks; by throwing the ball through poles, hitting the top of the pole or the pole itself, an individual or team scores. In a style of stickball played most often in Oklahoma, the objective is to hit a wooden fish on top of the pole. "In the social game played by the Cherokee, the whole community or clan would play. The men use sticks, and the women use their hands," Wildcat said. "The younger ones will be mentored by older players, and those with more skills will learn to be more compassionate to others. The fish is now carved from cedar, representing the black drum game fish. The poles are upwards of 30 feet." Stickball is a highly physical game that takes athletic ability, stamina and agility. It also takes skill to maneuver the sticks, which are made from hickory. Like lacrosse sticks, they have a small net on one end, in this case, made from deer hide strips. Wildcat brings pre-cut hickory lengths to his workshops. He shows and assists participants in heating and bending the wood. "They are gathered in the winter from fallen trees. We look for straight wood with tight grains. If the tree grows near water, the grains are larger and they aren't as good. Then the wood is soaked in water to kill any worms." From one hickory tree, Wildcat can make up to 40 sticks. He's refined the traditional methods to be more efficient, since the older ways yield only about 10 sticks per tree.

While historical stickball games could last all day, today they extend only about an hour. "People get tuckered out, especially if it's hot," Wildcat said. The stickball maker's invitation to Albuquerque came as a result of tribal connections to Wall, who is Jemez Pueblo and Chippewa. Wall knows cousins of Wildcat's, who traveled to Oklahoma reunions and played stickball. "I wanted to show my children that they are also part Cherokee and to know this part of their heritage," Wall said. "I really want my children to know their grandma was Cherokee and they have got relatives there and these are their traditional games. This is what they have from that side of their family." One featured piece in her show incorporates rotating slides of playing stickball and two sticks. Though only men played stickball in ancient times, it was the women who made the sticks. Today, Wildcat said for cultural preservation purposes, one must make his or her own sticks. Back home, he teaches the making of black locust longbows, flutes, baskets and necklaces, as well as conducts language competitions, stickball games, food and pottery expositions, and other cultural presentations. He also runs a summer youth camp where he teaches how to make Creek-style sticks. This is his first time teaching the stickball workshop outside his area. "There's great self-esteem for kids when they finish. When you make it yourself, it's great. Because that's how life is, you make it your own if you want it. No one is going to give it to you." |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Paul

C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

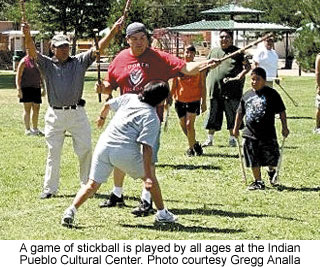

ALBUQUERQUE,

N.M. – During a cloudless weekend in July those curious about

Cherokee stickball visited the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center to

make sticks, hear the Cherokee language, and play a friendly game

of the ancient American Indian sport.

ALBUQUERQUE,

N.M. – During a cloudless weekend in July those curious about

Cherokee stickball visited the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center to

make sticks, hear the Cherokee language, and play a friendly game

of the ancient American Indian sport.  On

the second day of the workshop, Wildcat shows participants how to

attach and weave the netting that catches the ball. Once the handles

are turned, the stick is ready for play.

On

the second day of the workshop, Wildcat shows participants how to

attach and weave the netting that catches the ball. Once the handles

are turned, the stick is ready for play.