|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

August 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 8

|

||

|

|

||

|

Native Orphan Recognized

And Honored

|

||

|

by Doug Meigs, Indian

Country Today correspondent

|

||

|

credits: Photos by Doug

Meigs

|

|

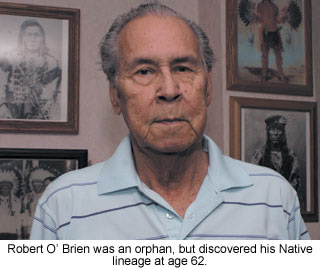

Robert O'Brien was an American Indian orphan. He grew up to become a leader of numerous Native outreach programs in Nebraska. On June 20, the Nebraska Urban Indian Health Coalition recognized O'Brien for his life of service. Tears welled in the eyes of Donna Polk-Primm, NUIHC executive director, as she presented him with an honorary plaque and star quilt. On top of his inspiring dedication to Nebraska's Native community, Polk-Primm knows his uplifting life story, how he retraced his lineage to "tribal royalty." From his birth Feb. 28, 1931 until early adulthood, O'Brien had never met another Indian. He spent his teenage years working for room and board on a farm in rural Minnesota. Friends at the small town school called him "Chief." He was a leader among the boys – strong, tall, articulate, president of the 4-H Club. O'Brien snuck into the Navy Reserve at age 16. His 20-year military career spanned enlistments in the Navy and Air Force; fellow soldiers often referred to O'Brien as "the Indian." He met a Native American for the first time while serving in France. The Navajo sergeant asked him about tradition, song and ceremony. "What tribe are you?" O'Brien had no answer. He grew up without one.

The boy introduced O'Brien to his father, Peter Thomas, a member of the Winnebago who was helping to organize a local Native community group in the late '60s. When O'Brien attended the first meeting, he had never seen so many Indians in one room. To his astonishment, they voted him president of the Indian Community Center Association, and O'Brien began his first immersion among people of America's First Nations. "When we were going out to the parking lot to get in the car, I thought, 'what in the hell have I gotten myself into?' Because I didn't know anything about Indians." They began with a dream of creating a Native health clinic for Indian people, and over the next 40 years, O'Brien helped guide the dream through the reality of numerous Native programs. In 1986, he helped establish the NUIHC. Shortly after, the state of Nebraska invited him to become an Indian commissioner. However, O'Brien said an influential naysayer protested that he didn't belong: "'He doesn't even know if he's Indian. We don't even know if he's Indian. He doesn't have an enrollment number.' So they withdrew the offer to be on the Indian Commission because I didn't have an enrollment number." Then, in 1990, IHS announced that he could no longer serve on the NUIHC board of directors. Without proper paperwork, he wasn't eligible. He began assembling the puzzle pieces of his origin story. On a summer road trip, he stopped by the orphanage where nuns raised him in St. Paul, Minn. The building was gone. After some research, he found a paper trail leading to his birth certificate. He found a name. Arthur Mandan. O'Brien learned his father was the first chairman of the Three Affiliated Tribes of Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara in North Dakota. His great-grandfather was Chief Red Buffalo Cow, the last recognized Mandan chief, who signed the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie. After 62 years without siblings, he had more family than he could have possibly imagined. He found a welcoming network of sisters, brothers, cousins, nephews, nieces and clan relations. And he learned of his mother. She was a nun (the orphan child of German immigrants). When she became pregnant, the Catholic Church spirited her back to Minnesota from the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. The church took her newborn child, who received an Irish name and a hidden identity. He grew up in the same orphanage as his mother. He enrolled in the TAT in 1992. The same year, he rejoined the NUIHC board of directors. Energized by positive momentum, he said, "We're going to make a go of this. "That's really all I wanted to do; for so long, we had heard people complaining and bringing up charts and graphs and showing how Indian health was the worst in the country. Everybody talked about how bad it was. … (I thought,) let's get in there and do something instead of sitting on our butts and complaining." Under his leadership, the coalition's annual budget grew from $300,000 to $2 million, and NUIHC established many key programs, including residential and outpatient behavioral health treatment, the "Tired Moccasin Elders Program," transportation, diabetes education/services, and HIV/AIDS testing and counseling. "If we could ever get the money to buy our buildings, I would love to rename them in honor of Bob O'Brien," Polk-Primm said. "We are who we are because of him." He retired from the NUIHC in 2006 and regularly chats over the phone with his remaining brother and sisters in North Dakota. As he sits in his living room, a picture of his father hangs over his shoulder. The black and white image shows Arthur Mandan shaking hands with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Mandan visited the president with a delegation to rescue a sacred bundle from the Heye Museum in New York. O'Brien's face is Mandan's reflection; they share facial features – the same high cheekbones, identical slicked-back hair. After a 1992 ceremony, they even share the same name – Mea Iràaxi Madoush "Spirit Woman." Tony Mandan said their father received the name from someone who saw a spirit woman in a vision. After a prolonged search, O'Brien found his mother, Marie (Gdanietz) Bruestle, and he hugged the former nun outside her home in Mendota, Minn. She lived her final years in Omaha with her lost son. The broken circle of their lives mended. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Paul

C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

OMAHA,

Neb. – He was an Irish kid until the first grade. Then, the

orphanage children discovered cowboys and Indians. Ever after, he

was "the Indian." Only later in life would he discover that his

blood carries not a drop of Irish heritage.

OMAHA,

Neb. – He was an Irish kid until the first grade. Then, the

orphanage children discovered cowboys and Indians. Ever after, he

was "the Indian." Only later in life would he discover that his

blood carries not a drop of Irish heritage. He

moved to Omaha after being stationed at Offutt Air Force Base. On

a stormy afternoon, he noticed a soggy paperboy seeking refuge from

the elements. O'Brien invited him inside for hot cocoa. Surprised,

the boy stared and said, "You're an Indian, aren't you!" The paperboy

was Indian, too.

He

moved to Omaha after being stationed at Offutt Air Force Base. On

a stormy afternoon, he noticed a soggy paperboy seeking refuge from

the elements. O'Brien invited him inside for hot cocoa. Surprised,

the boy stared and said, "You're an Indian, aren't you!" The paperboy

was Indian, too.