|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

August 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 8

|

||

|

|

||

|

Director Chris Eyre:

10 Years After Smoke Signals

|

||

|

by DAVID HOFSTEDE -

Cowboys and Indians Magazine

|

||

|

It is May of 2009, and director Chris Eyre is where all directors dream of being — in demand and busy with a number of high-profile projects.

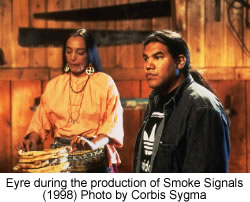

Also on the itinerary, however, is hitting the road for two screenings of Smoke Signals, the film he directed more than 10 years ago, and for which he is still best remembered. "I don't know if that's a good thing or a bad thing," he says, with a mix of pride and resignation. "On the good side it's a wonderful story about forgiveness, and I think in 20 years it will hold up. I've made several more movies since then, and I think I've done some better work, but Smoke Signals is still the one everyone remembers best. I wonder if I'll be known better for a movie after that, but either way, I'm fine." As first impressions go, it's easy to understand why Eyre's feature directorial debut remains so prominently attached to his name. Smoke Signals (1998) won the Sundance Film Festival Filmmakers Trophy and the Audience Award, and it was hailed as a breakthrough film that transcended stereotypes to capture contemporary Native American lives and humor. The film received not just glowing reviews but also major coverage in The New York Times, Time magazine, and other influential media outlets. Most of the stories played up the novelty of a theatrically released film from a Native American director. Some claimed this was the first time that had happened, though there were Native American directors as far back as the silent era. But the point, if not technically accurate, was still noteworthy — after nearly a century of being defined by westerns, here was an Indian with a different story to tell about the Native American experience.

Approaching the sometimes-prickly Alexie with that request, armed only with a thin resumé and nonexistent track record, was his first challenge. But Eyre has always been one to visualize his goals before setting out to achieve them. "I remember after high school traveling to the University of Arizona and a woman asking me what I want to do, and I said that I was a director," Eyre recalls. "Then she asked what I had directed, and I said, 'Well, nothing yet.' My thing is you have to say it before it comes to pass." It was a high school photography class — and the historical Native American images of Edward Curtis — that inspired Eyre into his career behind the camera. "It came from wanting to touch those people. I kept wondering who they were," he says. The desire to connect with his Indian heritage was particularly strong in Eyre, an Indian of Cheyenne-Arapaho descent who grew up as the adoptive son of white parents in Klamath Falls, Oregon. At age 25 he found his birth mother. "I had 10 years with my biological mother before she died, and afterwards I was still angry that she left me twice." Hardly surprising then that a yearning for family and roots has been a prominent theme in his filmography. "Smoke Signals is a great example of 'home,' " he says. "It's about a boy who misses his estranged father, then the father dies and he doesn't get to reconnect with him." While attending NYU's graduate film school, Eyre wrote and directed Tenacity (1995), a short film about a confrontation between Indian boys and a group of rednecks. The film earned him awards and grants, as well as the courage to approach Sherman Alexie. "He had to prove himself," Alexie told the Los Angeles Times of that first meeting. "I'm one of the biggest Indian writers in the country, he wants to do a film based on my book, and he showed up 20 minutes late. I thought, He's Indian." Using material from a chapter in Alexie's book The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven titled "This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona," the author adapted his novel into the screenplay for Smoke Signals.

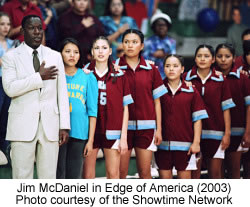

"I felt it was a challenge I was ready for, but I still didn't know what I was doing to a large degree," Eyre admits. "I'll never forget waking up the night before we started shooting and seeing 18-wheelers appear overnight in the parking lot for a 100-person crew. Millions of dollars were being spent and I was supposed to be in charge. Just show up and figure it out — that's the way I've always done it." Apparently he figured it out right. The film was screened at the White House and described by Time magazine as "a shrewd portrait, sly, casual yet palpably authentic, of the principal ways members of any minority try to respond to an uncomprehending world." Eyre's next film, Skins (2002), was a tale of murder, brothers, and blood. Starring Graham Greene and Eric Schweig, the movie was filmed entirely on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota — once home to Red Cloud and the site of the Wounded Knee siege of 1973. Lacking the comedic moments of Smoke Signals and opening after the zenith of the independent film movement, Skins did not attract a wide audience, though it was selected to close the 2002 Human Rights Watch International Film Festival. It fittingly received its most enthusiastic reception on reservations like the one where it was filmed. First Look Pictures created the "Rolling Rez Tour," a series of free screenings at Indian reservations throughout the country. Edge of America, about an African-American high school teacher (NYPD Blue's Jim McDaniel) whose preconceptions about Indian culture are challenged when he coaches a girls' basketball team at a Utah reservation school, was selected as the opening night film of the 2004 Sundance Film Festival and brought Eyre a Directors Guild of America award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement. Though this touching and perceptive film didn't reach the audience it deserved, it did find a fan at NBC, who admired Eyre's handling of an inspirational sports story and invited the director to visit the set of Friday Night Lights. Eyre directed "Keeping Up Appearances," the seventh episode of the series' 2008 season, and later helmed an episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. "We shot a 48-minute episode in six days," Eyre says of his Friday Night Lights experience. "It's blazing fast and exciting, and a great ride when you're working with actors that are stellar in their performances." The series' loose and free-flowing camerawork offered an ideal match with Eyre's evolution as a filmmaker. "When I was getting started I didn't know anything about style. I think whoever directed Cannonball Run was my hero," Eyre says. He studied film theory at the University of Arizona and had a breakthrough while taking courses in Japanese cinema. "My favorite director was Yasujir Ozu, who made movies like A Story of Floating Weeds (1934) and The Only Son (1936), which were basically home dramas shot in a piecemeal style. Ozu didn't use dollies, pans, or tilts. What he had were still photographs with actors in the frame. That's where I identified my original style." Compare Smoke Signals with Eyre's more recent projects, most notably We Shall Remain, and you might think you're watching the work of a different director. "If you watch the third part of the series, you'll see how I've diversified my visual style," he says. Though he once said, "The only thing you get in making period pieces about Indians is guilt," Eyre accepted the challenge of participating in one of the most ambitious television series on Native history ever produced, involving a multifaceted story of Native perseverance that spans three centuries — from the battles of the Wampanoags of New England in the 1600s to the American Indian Movement leaders of the 1970s.

Eyre had the daunting task of shaping a balanced portrayal of Major Ridge, played by Wes Studi. Ridge was a prosperous Cherokee landholder who decided it was in the interest of his people to give up an independent Cherokee homeland in the southern Appalachians in hopes of peace and resettlement in land west of the Mississippi. It is remembered as one of the most shameful chapters in the history of U.S. relations with Native Americans. "I hope Wes Studi and I have made him into a three-dimensional human being who was not a noble or a savage," Eyre says. "Ridge was a man who had to make a choice, and he made the best one he could for the preservation of his people, but he was damned either way." Being a go-to director for Native American projects has been a boon to Eyre's career, but he's also gratified when he's invited to take on a project that does not have an Indian component. After making Smoke Signals, he was offered the director's chair on the Rob Schneider comedy Deuce Bigalow, Male Gigolo. He turned it down. Even though the film was nobody's idea of a classic, the chance to do it still qualifies as progress for Eyre and for Hollywood. "I'm happy to make films I'm passionate about, and that's what I've done," he says. "If the subject is Native American, I think I can go to a place that's richer than other filmmakers, but it's not the driving force for me. It's more important to try and transcend even that." Currently Eyre is developing A Year in Mooring, a supernatural drama that is not related to the Indian experience, but he also hopes to film the story of the controversial Native American activist Leonard Peltier. "After that, I'd like to do Dances with Wolves in the style of Blazing Saddles," Eyre says. Of course, given the current climate of political correctness, it's doubtful that Blazing Saddles could get made today. A Native American version could really stir up trouble. "I know," Eyre says. "That's why it would be great!" |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Paul

C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

We

Shall Remain, a five-part documentary on the Native American experience,

for which he directed several episodes, is playing on PBS to glowing

reviews. He's attempting to launch a new theatrical film and awaiting

an invitation to return to the TV series Friday Night Lights after

directing an episode from the previous season.

We

Shall Remain, a five-part documentary on the Native American experience,

for which he directed several episodes, is playing on PBS to glowing

reviews. He's attempting to launch a new theatrical film and awaiting

an invitation to return to the TV series Friday Night Lights after

directing an episode from the previous season.  "When

I read Sherman Alexie's story 'This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix,

Arizona,' I knew that was the movie I wanted to make," Eyre

says. "His writing hit upon something that I related to in

a very deep way."

"When

I read Sherman Alexie's story 'This Is What It Means to Say Phoenix,

Arizona,' I knew that was the movie I wanted to make," Eyre

says. "His writing hit upon something that I related to in

a very deep way."  The

story focuses on two young Indians, Victor (Adam Beach) and Thomas

(Evan Adams), who travel from Idaho to Arizona to pick up Victor's

father's ashes. Filmed in 22 days on a $1.7 million budget, Smoke

Signals grossed more than $8 million at the indie box office.

The

story focuses on two young Indians, Victor (Adam Beach) and Thomas

(Evan Adams), who travel from Idaho to Arizona to pick up Victor's

father's ashes. Filmed in 22 days on a $1.7 million budget, Smoke

Signals grossed more than $8 million at the indie box office.  "I

always thought historical things with Indians were so cliché

and so uninteresting. You had Indians in loincloths running from

a tree to a rock, firing a gun, screaming, and then they die, romantically.

There was something perverse about it," he says. "But

in conversations about We Shall Remain, I found they wanted to have

Native American protagonists who participate in their own history

and weren't merely victims of what happened."

"I

always thought historical things with Indians were so cliché

and so uninteresting. You had Indians in loincloths running from

a tree to a rock, firing a gun, screaming, and then they die, romantically.

There was something perverse about it," he says. "But

in conversations about We Shall Remain, I found they wanted to have

Native American protagonists who participate in their own history

and weren't merely victims of what happened."