|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

July 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 7

|

||

|

|

||

|

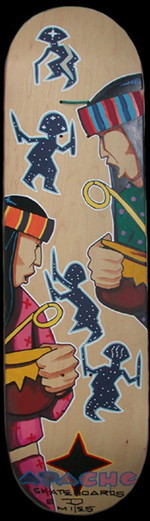

Apache Skateboards:

A New Native American Iconography

|

||

|

by KATHY WISE - Cowboys

& Indians Magazine

|

||

|

credits: Photography

by Brendan Moore

|

|

Apache Skateboards — the first Native-owned skateboard company — is championing these new concrete warriors, translating an ancient heritage onto the silk-screened deck of a skateboard.

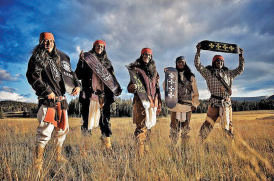

"There is nothing better than the feeling of pushing the wood under your feet, the adrenaline rush of skating down stairs, or the little accomplishment of landing a kickflip," enthuses Razelle Benally, one of two female members of the Apache Skateboards team. "There is nothing else that can replicate that feeling of accomplishment, of knowing that you put forth the effort and skill to land a new trick." Half Navajo and half Lakota, Benally was recruited by Douglas Miles, team leader and founder of Apache Skateboards, after he spotted her dropping in the pipe at the San Carlos Skate Park one night. Ranging in age from 11 to 25, the eight team members also include Tracy Polk Jr., Douglas Miles Jr., Keith Secola, Reuben Ringlero, Irwin Lewis, Tony Steele, and Tashadawn Hastings. The team is a family affair: In addition to Miles' son, Doug Jr., Ringlero is Miles' nephew.

Ringlero has emceed team events throughout the country, working with tribes like the Gila River in Arizona, the Chemehuevi in California, the Red Lake Ojibwe in Minnesota, and the Jicarilla Apache in New Mexico. "For me," Ringlero says, "it's about giving back as a skateboard company to kids who don't have many options where they come from. The cool thing about skateboarding is that you can do it anywhere — a curb, a parking lot — you don't necessarily need a skate park. It is just you and your board and you're having fun." Ringlero grew up in Komatke, Arizona, on the Gila Indian Reservation, where he now lives with his wife, Deanna, and their 3-year-old son. "Skateboarding wasn't popular at all on the reservation when I started," he says. "Everybody was into drugs and gangs and causing trouble, and my friends and I just wanted to skate. Skateboarding has definitely grown since then. There are skate parks now in San Carlos and Gila River, and kids are starting to see the fun that we have." Made popular in the '60s and '70s by California teens who developed daring tricks in abandoned amusement parks and empty swimming pools, skateboarding has always had an outlaw reputation. Now it has a new face — and a new design — thanks to Miles, who is turning the world of skateboarding on its edge. Miles channeled his teenage penchant for graffiti into a successful career in fine art, creating provocative, graphic spray-painted stencils that meld pop culture images from The Godfather and Apocalypse Now with gun-toting Apache warriors. But it wasn't until his son took up skateboarding at age 11 that Miles got back to the boards of his youth, necessity becoming the unexpected mother of Apache Skateboards.

His first design was a simple anime- inspired image of an Apache warrior on the skateboard deck. Not only did his son love the board and ride it around San Carlos until it broke, but he came home and informed his dad, "Everyone wants one." Miles realized he couldn't hand-paint a skateboard for all of the teenagers in San Carlos, so he saved up money from the sale of his artwork and found a company in California to print the first 100 skateboards. That was in 2003. Now, in addition to the silk-screened decks, Miles creates handpainted skateboards that are part of the permanent collections of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis, the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey, the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, and the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. Miles sees his deck designs, and the team, as an opportunity to share cultures — both the tribal culture of the Apache and the tribal culture of skateboarding. "Surfing was created by native Hawaiians," Miles says, "and was brought to the mainland in the '30s. Surfers and skateboarders inherently are very tribal about the way they do their thing. As tribal people, as Apache, we understand that, and it is a perfect fit." As members of the fringe, skateboarders — like punk and hip-hop artists — have created their own language, attire, movement, sound, and art, which are often viewed as primitive, or unsophisticated, or unworthy of appreciation by members of the cultural mainstream. Even

Native art, which is lauded when it meets historic artistic standards,

is often devalued when it takes a less traditional approach. Miles

thinks that it's time to recognize the aesthetic power of a new

kind of tribal art, one that exceeds all limitations.

My generation has to deal with a certain identity crisis, about how to break the mold without breaking our traditions, how to balance my ancestral blood while progressing with the rest of the people in this world. It's a hard thing to do, but through Apache Skateboards I'm able to uphold my background and not forget who I am," she says. Who she is is proof that you can't judge a boarder by the baggy clothes. Benally started skating when she was 13 years old, but she stopped at 16 to focus on school because she wanted to get into a good college. She studied mathematics and physics, then became interested in filmmaking at the end of her senior year.

"Skateboarding and filmmaking go hand in hand," Benally says. "Skateboarding is a very spectatorial sport, a very visual sport. I want to capture on film that feeling of landing a trick, that feeling of the wind in your hair as you push faster and faster, to show it to others." As she frames her shot, watching a team member stand above the obstacle he is about to 360 flip, Benally wonders what is going through his mind. "I try to capture that feeling of Ollieing off, and the emotion behind the trick. Because it is a special thing, and not many people on this earth are going to know that feeling personally. It is my job to provide the visual image to capture the emotion." Benally and Ringlero can be found behind the lens, and riding the ramp, at the team's big annual event — the Apache Skate Blast — held every spring at the San Carlos Skate Park. Miles' mom cooks fry bread and beans for the sponsors, and the team hosts a punk rock concert for the participants. "Our idea is to get skaters far and wide to come and skate and have a good time," Ringlero says. "Hopefully every kid can go home with a prize. A couple of major companies in the valley have made donations, and that's how we get skaters far and wide, not just Native skaters, to see what the reservation has to offer and what talent we have." They hope to foster the talents of other kids by example. "We're not your stereotypical Indians," Benally says. "We're not your stereotypical kids in general. We're all different, and we're using those differences to create inspiration and influence for other people who may not know they have options. When we travel to different reservations, the kids may be able to draw well, to paint; they may be into graffiti. But in the society they live in, those talents go unnoticed. When we come to those places, we let them know that those talents are worth something. Because we all have those same talents, and we're doing something with them." "Apache Skateboards is unique," she says, "because we are combining diverse backgrounds, talents, and different means of expression into one embodiment. We are all, to some extent, artists and poets. We all skate, we all care about progressing ourselves and each other. We push each other to skate better, to make better films, to live better, to live more interesting lives. You're not going to find another team like us." Miles himself can't contain his enthusiasm for his team. "I can't express how proud I am of them, but it is very nerve- wracking because they are still kids. It's like herding cats. But I wouldn't take anything for it, because they are artists in their own right. And they inspire me to no end. They are Apache Skateboards." But he has concerns, too. About recognition and acceptance of new Native art forms. About ensuring that Native Americans are able to own their new imagery, without being culturally hijacked. About tribal concerns for legal liability standing in the way of building new skate parks. But people are taking notice, and skate parks are getting built. "I think a lot of what we do will impact how Native Americans are going to be viewed in the 21st century," Miles says. "People are going to say 'Wow.' It is about a new Native American iconography, a totally different way of looking at Native American youth in the 21st century." To see more of Brendan Moore's photos of the Apache Skateboards team, visit www.brendanmoorephoto.com. APACHE CHRONICLES The

Artwork of Douglas Miles

SKATEBOARDS

ON FILM

EVENTS All

Nations Skate Jam Apache

Skate Blast Sac

City Throw Down RESOURCES •

Apache Skateboards |

||||||

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Paul

C. Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

"I

have been with Apache Skateboards since the beginning, when we took

our first trip to Cali to get our first batch of skateboards,"

Ringlero says. Based out of the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation

in Arizona — which Miles calls home — the team travels

the country doing street-style demos, hosting skateboard contests,

and teaching skateboard basics and safety at schools.

"I

have been with Apache Skateboards since the beginning, when we took

our first trip to Cali to get our first batch of skateboards,"

Ringlero says. Based out of the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation

in Arizona — which Miles calls home — the team travels

the country doing street-style demos, hosting skateboard contests,

and teaching skateboard basics and safety at schools.  "I

could not afford the full-color name-brand skateboard that my son

wanted at the mall," Miles says. "Indian people for centuries

have made a world out of the things around them — pots out

of clay, bows out of reeds. I don't want to get all anthropological,

but I found a way to work with the tools and resources I had."

"I

could not afford the full-color name-brand skateboard that my son

wanted at the mall," Miles says. "Indian people for centuries

have made a world out of the things around them — pots out

of clay, bows out of reeds. I don't want to get all anthropological,

but I found a way to work with the tools and resources I had."

His

skaters are all about forging a modern tribal identity. "When

I first tell people about Apache Skateboards," Benally says,

"they superimpose an image of us just being Native, but we're

not concerned about sticking to what's Native, or sticking to anything

that will limit ourselves.

His

skaters are all about forging a modern tribal identity. "When

I first tell people about Apache Skateboards," Benally says,

"they superimpose an image of us just being Native, but we're

not concerned about sticking to what's Native, or sticking to anything

that will limit ourselves.  She

went on to become a film student at the Institute of American Indian

Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and now serves as team filmographer

along with Ringlero, who got his degree in media arts in Tempe,

Arizona.

She

went on to become a film student at the Institute of American Indian

Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and now serves as team filmographer

along with Ringlero, who got his degree in media arts in Tempe,

Arizona.