|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

June 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 6

|

||

|

|

||

|

Swapping Knowledge

About Wampum

|

||

|

by Kara Briggs

|

||

|

credits: photo be Stephan

Lang Photography

|

|

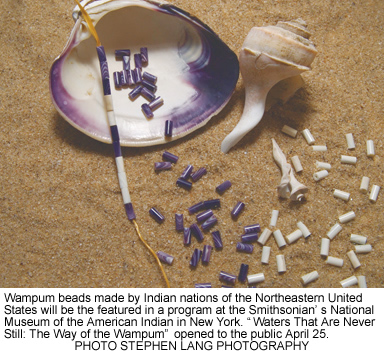

NEW YORK – Wampum - tiny, beautiful ground-down shell beads - for centuries wielded an intrinsic power far beyond its size and scale. Sacred to the Native peoples of the Northeastern United States, wampum was essential in many of life’s most profound exchanges, such as negotiating marriages and paying tribute to other powerful nations.

The fascinating subject of the wampum trade will be explored in a program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York on Saturday, April 25. “Waters That Are Never Still: The Way of the Wampum” is a hands-on program in recognition of the 2009 Hudson-Fulton-Champlain Quadricentennial, the 400th anniversary of Hudson and Champlain’s voyages along the river and lake now bearing their names. The museum program will feature artists and historians from Indian nations, which continue to use wampum in their art and sacred practices. Among the participants are Perry Ground, Onondaga; David Martine, Shinnecock and Apache; Yvonne Thomas, Seneca; Ken Maracle, Cayuga; Allen Hazard, Narragansett; and Jonathan and Elizabeth Perry, Aquinnah Wampanoag. Wampum has been made for centuries by the Indian nations in New England and New York using quartz drills. Production increased exponentially with the introduction of European tools such as metal drill bits, said Martine, director of the Shinnecock Nation Cultural Center and Museum in Southampton, N.Y. The value of the beads to Indian nations even prompted the Europeans to get involved in their production. “The Dutch realized there is a natural resource that the Native people desire, so why ship things across the ocean,” said Ground, who teaches in the Native American Resource Center of the Rochester (N.Y.) City School District. “Why not set up a factory, pick them up off the beach and trade for beaver furs?” It’s hard to imagine the economic muscle of trade goods such as wampum or beaver pelts in 1700s New York. “We look at lists, like you could trade 100 beaver pelts for cows or a house,” Ground said. “The beaver pelt wasn’t as valuable to a Native person as wampum beads, which they could get by the hundreds and hundreds for beaver pelts.” Wampum continued to be used by the nations even after the beaver were depleted and the large-scale production of wampum ended. Many people from wampum-making cultures found themselves in need of other kinds of work by the 1800s, said Martine. The Shinnecock, for example, who had been whalers, joined the commercial whaling industry. Although the practice of wampum-making diminished, its use continues today. In contrast to the more modern rainbow of glass beads used by Indian nations in other parts of North America, Native people from the Northeast use white and black or purple wampum almost as a signature design. “It has warmth to it because the shell work has a rich quality to it,” Martine said. “The color is rich and the feeling is rich. Real wampum is still rare and valuable.” Each bead is worth $5 to $6. Ground believes it is important for Native Americans to continue to use wampum. Among the Haudenosaunee, each of the 50 chiefs in the Grand Council has a string of wampum that shows their position. “As one chief passes away and another is put in that position, that wampum is passed to that person,” Ground said. “It is still an emblem of their authority.” |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008 of Paul C.

Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Created

from the purple growth ring of quahog clam shells and the inner

whirl of whelk shells, these beads - less than an inch long and

about an eighth of an inch thick - traveled along the Hudson River

trade routes from the Atlantic Ocean hundreds of miles west to the

Great Lakes and beyond with the beaver trade.

Created

from the purple growth ring of quahog clam shells and the inner

whirl of whelk shells, these beads - less than an inch long and

about an eighth of an inch thick - traveled along the Hudson River

trade routes from the Atlantic Ocean hundreds of miles west to the

Great Lakes and beyond with the beaver trade.