|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

April 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 4

|

||

|

|

||

|

Menominee Tribe Makes

Effort To Keep Language Alive

|

||

|

by Meg Jones of the

(Milwaukee, Wisconsin) Journal Sentinel

|

||

|

credits: Photos by Gary

Porter - The (Milwaukee, Wisconsin) Journal-Sentinal

|

|

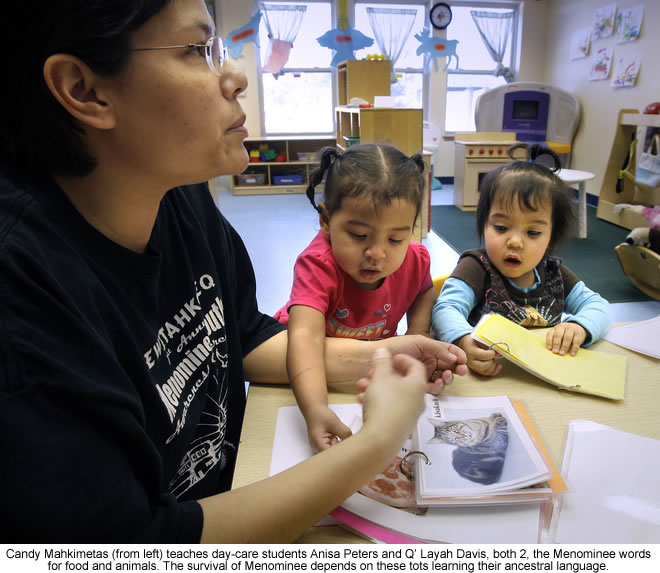

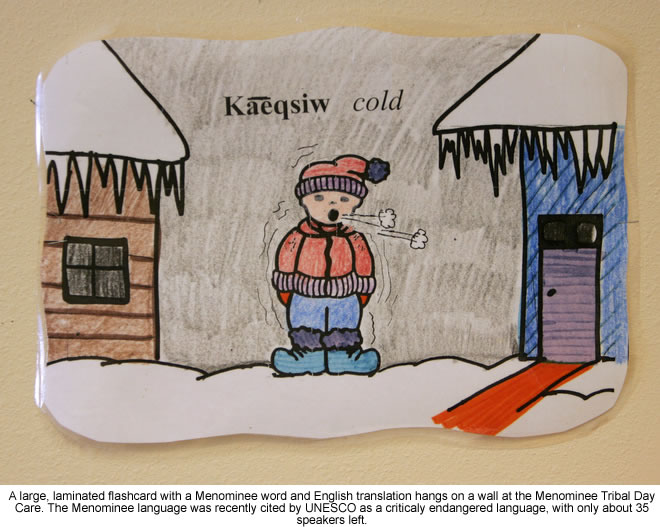

Seated at a small table, bare except for a label taped to the top that read atuhpwan - the Menominee word for table - the tiny students spoke what sounded to an untrained ear like gibberish. Using a booklet of flashcards held up by their teacher, the 2-year-olds pointed and repeated the words kuapenakaehsaeh (cup), aemeskwan (spoon) and paeces kahekan (fork). At home they've been known to ask their families for a snack using the Menominee words for crackers and fruit instead of English. "Their minds are like sponges," said their teacher Candy Mahkimetas, after quizzing them on the words for bear, dog and cat. "This is the crucial age for them to start speaking." The survival of the Menominee language - which has only an estimated 35 fluent speakers - depends on these tots at Menominee Day Care Center learning the language their ancestors have spoken for centuries. Last month, UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, released a new world atlas of endangered languages - almost 2,500 that are at risk of becoming extinct or have recently disappeared. Menominee, along with languages of two other Wisconsin tribes - Oneida and Potawatomi - is listed as critically endangered.

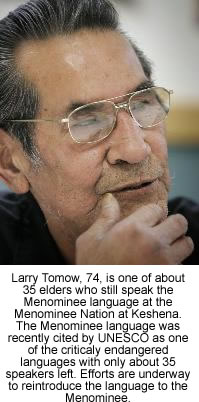

The average age of the few dozen remaining native speakers is in the mid-70s, and some of the elders who speak the language are in ill health. However, the tribe has 10 trained Menominee language instructors who teach in the schools and College of Menominee Nation. The language is taught in day care and kindergarten through middle school. At the high school, it's a popular elective taken by three-quarters of the students. Language instruction is also offered to adults at the tribe's recreation center. It's billed as elder re-learning sessions for those who grew up listening to the language. Twelve to 15 people show up each week. "A lot who come to the class say, 'Oh, I remember my grandmother saying that,' " said Karen Washinawatok, 59, director of the Menominee Language and Culture Commission. The commission trains substitute language teachers, works on language curriculum and helps with a University of Wisconsin-Madison project compiling a beginner's dictionary of the Menominee language. The tribe has also converted hundreds of hours of audiotapes of elders speaking stories, which were recorded decades ago, into digital versions that can be downloaded on iPods and laptops. Menominee was the first language Larry Tomow, 74, learned to speak. "My grandma and grandpa taught me. My older brothers and sisters could speak it better," said Tomow. "When I got to school, the kids said I talked funny, and I stopped." But Tomow continued speaking Menominee at home and never forgot it. Now he talks to other elders in the native language and goes to the re-learning sessions with his wife, Ione Tomow, 71, who is learning to speak it. "The words are very long, and the pronunciation is different," said Ione Tomow. "He speaks it so fast, it's hard to keep up with what he's saying." The Menominee language wasn't always embraced. Elders remember a time when they and their ancestors were discouraged and even punished by schoolteachers for speaking anything but English. Though Menominee has survived, that attitude is one of the reasons behind the extinction or near death of many tribal languages in North America. Of the 400 to 600 North American tribal languages thought to have existed, just 175 are left, with only about 20 still spoken and used by all ages of tribe members, said Inee Slaughter, executive director of the Indigenous Language Institute in Santa Fe, N.M. The loss of a language is the loss of a nation's culture.

The decline of tribal languages was hastened in the 19th century when the federal government systematically attempted to assimilate American Indians by sending children to boarding schools where they spoke only English. Not only was the prestige of the tribal languages lost, but social domains of language shifted to English, said Bernard Perley, assistant professor of anthropology at UWM who spoke Maliseet at his New Brunswick, Canada, home until he learned English in elementary school. If tribal leaders had to negotiate with the U.S. government, it was in English. "A lot of speakers would feel stigmatized when they used their native languages," said Perley, who earned his Harvard doctorate studying the causes of language deaths. When Warren Wilber, 62, was a youth on the Menominee reservation, he had never heard his parents speak the language, until one evening when an older couple stopped at their home for help because their car had stalled. Wilber heard his mother speak to the older woman in Menominee. "I was so surprised. I didn't know she could speak the language," Wilber said of his mother.

Verbs are used differently depending on the nouns, which are considered either animate or inanimate. Animate objects can be something that non-Menominee speakers would consider inanimate, however. Words like rock, tree or bread as well as native foods and plants are considered animate, said Teller, while anything imported, such as oranges or bananas, would be inanimate. "What makes the language unique is that if you're going to eat steak, you'd use a different word for eat because (steak is considered) inanimate. If it's apple, which is animate, you'd use another word for eat," said Teller. In addition to teaching Menominee language at the college, Teller is also the tribe's language liaison and works with instructors to improve their teaching and speaking skills.

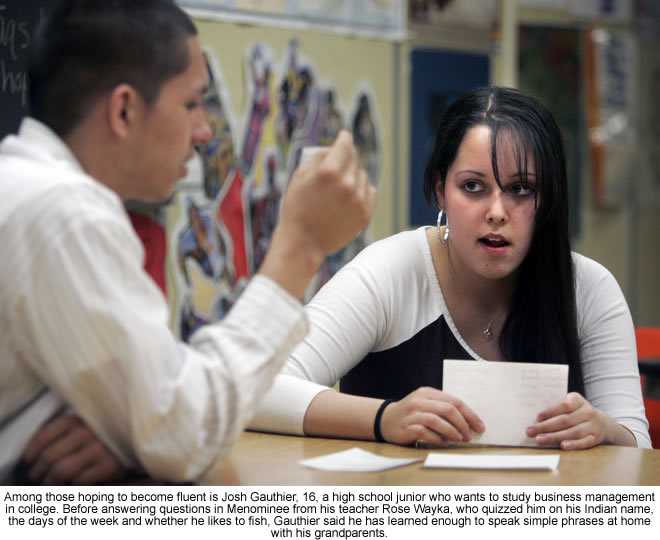

And of course there are words for things Menominee speakers centuries ago could not foresee. A computer is referred to as "metal that speaks" and pizza is "flour with meat on top." There's no word yet for iPod, Teller said, but it's possible the digital recording devices might someday be called "little metal that speaks" in Menominee. At College of Menominee Nation, first- and second-year language classes are taught each semester, and when there are enough students, advanced classes are offered. At the high school, students who study Menominee can apply their credits to college language requirements. But Teller noted that, like any second language, fluency depends on many years of commitment. "The school setting provides only a limited literacy rate. It takes a lot of dedication to become fluent," said Teller, 55. Among those hoping to become fluent is Josh Gauthier, 16, a high school junior who wants to study business management in college. Before answering questions in Menominee from his teacher Rose Wayka, who quizzed him on his Indian name, the days of the week and whether he likes to fish, Gauthier said he has learned enough to speak simple phrases at home with his grandparents. "You need two years of foreign language for college, and I thought this would be interesting," said Gauthier.

|

Keshena, Wisconsin map |

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008 of Paul C.

Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Keshena

- The future of the Menominee tribal language had just awakened

from naps.

Keshena

- The future of the Menominee tribal language had just awakened

from naps. But

the Menominee didn't need the United Nations to tell them their

language is at risk.

But

the Menominee didn't need the United Nations to tell them their

language is at risk. "So

when the last of the speakers are gone, basically that whole library

of knowledge is gone. It's not just the language, but the history,

wisdom, the sciences, the stars and plants - they're all gone,"

said Slaughter.

"So

when the last of the speakers are gone, basically that whole library

of knowledge is gone. It's not just the language, but the history,

wisdom, the sciences, the stars and plants - they're all gone,"

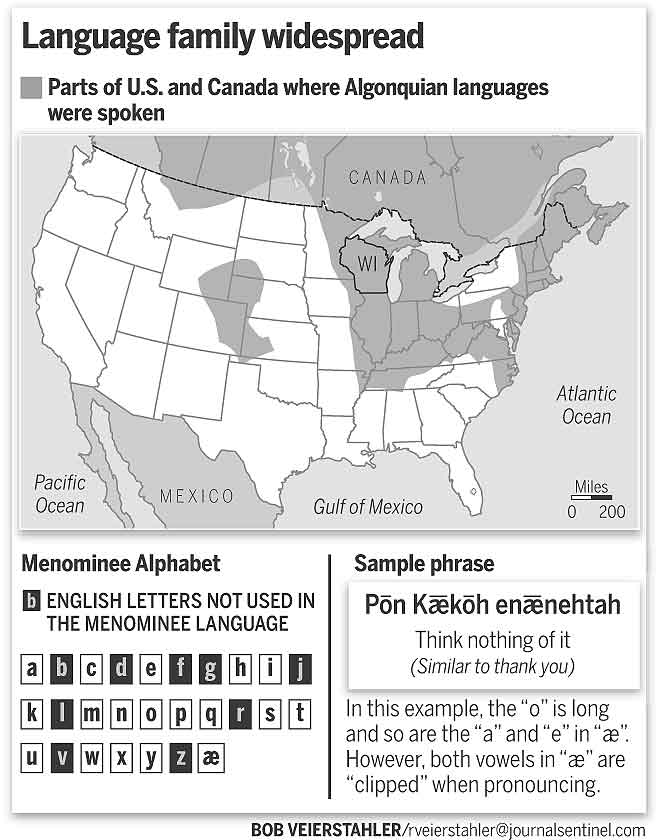

said Slaughter. Menominee

is an Algonquian language, which were among the first encountered

by Europeans and because of that, many place names in the East and

Midwest, including Wisconsin and Milwaukee, are derived from Algonquian

words. The Menominee language uses 17 letters of the English alphabet

plus a letter that combines "a" and "e" with

"q" pronounced as a glottal stop, explained John Teller,

a former tribal chairman who teaches the language at the College

of Menominee Nation in Keshena.

Menominee

is an Algonquian language, which were among the first encountered

by Europeans and because of that, many place names in the East and

Midwest, including Wisconsin and Milwaukee, are derived from Algonquian

words. The Menominee language uses 17 letters of the English alphabet

plus a letter that combines "a" and "e" with

"q" pronounced as a glottal stop, explained John Teller,

a former tribal chairman who teaches the language at the College

of Menominee Nation in Keshena. It's

often difficult to translate Menominee into English because sometimes

one Menominee word can be an entire sentence, Teller said. A word

like waepew means "he/she is running" while naewaew means

"he/she sees him/her." Like many tribal languages, there

are Christian influences, such as the days of the week: Sunday is

called prayer day and Friday is fasting day.

It's

often difficult to translate Menominee into English because sometimes

one Menominee word can be an entire sentence, Teller said. A word

like waepew means "he/she is running" while naewaew means

"he/she sees him/her." Like many tribal languages, there

are Christian influences, such as the days of the week: Sunday is

called prayer day and Friday is fasting day.