|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

February 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 2

|

||

|

|

||

|

Retelling Of Indian

Tales Can Conflict With Culture

|

||

|

by Rob Chaney - The

Missoulian

|

||

|

credits: photos by Rob

Chaney - The Missoulian

|

|

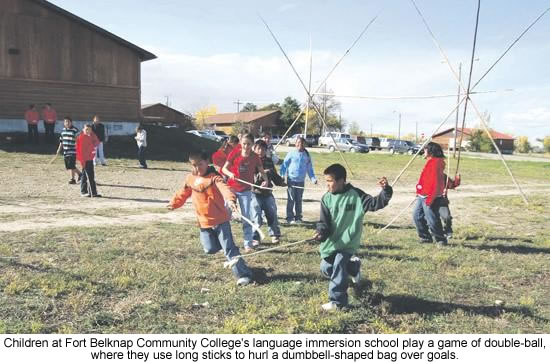

Finally, he looked up in frustration and saw the bull berries growing on a branch overhanging the water. He'd been hasty and got reflections instead of the real thing. Getting Indian stories into books can be a similar exercise. At Fort Belknap Community College, Allen has been telling stories to fellow teacher Sean Chandler's video camera. As one of the few remaining fluent Assiniboine speakers on the Fort Belknap Reservation, Allen is a living chapter of the Montana Tribal History Project. Such trickster stories live all over Montana. The Oglala know him as Inktomi, a consonant away from Allen's Assiniboine language. To the Blackfeet, he's Napi. The Gros Ventre call him Niant. The Salish, Crow and Cheyenne call him Coyote or Old Man Coyote. Like Aesop's fables in ancient Greece or Anasi, the spider-man of West Africa, Inkdomi's stories usually have a moral or lesson. "He's supernatural," Allen said. "He can do things no ordinary person can do. But he does all these things so students can learn not to do that."

Researchers look to people like Allen for help. She was raised by her grandparents, a practice common among Montana tribes where certain children are chosen to learn the deep traditions of the clan. She grew up to become a teacher and helped create one of the first native-language classes for children in the Hays Elementary School system in the 1970s. Allen, a board member of Fort Belknap Community College, is one of fewer than a dozen fluent Assiniboine speakers on the reservation. She's on the fence separating jealously guarded old ways and the education of unborn generations. "Usually, Inkdomi stories were only told in the fall and winter months," Allen said. "With modern times, you don't have to follow the rules that much. Besides, it's been done so much that it's never been followed." Other tribes want stricter standards. Julie Cajune, director of the Salish Kootenai College Tribal History Project, hopes that teachers will stay within the rails of a similar cold-weather tradition. Her living-room window looks out at the snow-covered front of the Mission Mountains, but she said that wasn't enough. "The tradition for Coyote stories is they can't be told until after the first heavy snow, or when the trees pop at night," Cajune said. "It has to be really cold. You're supposed to put them away at certain times. In Cheyenne tradition, they can only be told at night. That's tough for teachers. I don't know how to address that." Allen said there could be several reasons for the cold-weather rule. Scarcity increases value. Limiting favorite stories to wintertime was a good incentive to keep kids behaving when they're stuck inside a tepee during bad weather. And the anticipation makes them easier to remember later.

"The work that I did was based on generations of work already done, all at the expense of the tribes," Cajune said. "There's 30 years of collecting interviews, 10 years of filming. I don't have the right to turn it over to the state. Had people thought this would become state property, nobody would have talked to me." Copyright remains a sensitive issue for tribal historians. It's hard enough for many clan elders to pass on their oral tradition to someone who hasn't earned the right of transfer, as the Blackfeet call their storytelling authority. Harder still is the idea that one more remaining Indian possession might become a trinket in some white school's trophy shelf. Still, time is erasing the knowledge. Fort Belknap videographer Sean Chandler was nearing the end of his video interviews when an elder named Josephine Mechanace called him. She gave him a demonstration of Assiniboine breadmaking. A week later, she died. "I knew these DVDs were for educators," Chandler said. "But we looked at it from a different aspect. "The first people who should benefit from this are our own people. We're getting mixed reactions. People were under the impression that we were building a curriculum that gets plopped on a desk. We felt that was way too limiting. If you knew how our history and culture were attacked and stomped on, you'd understand." What

not to do Verne Dusenberry was an acclaimed scholar with Montana State University in Bozeman and Northern Montana College in Havre from the 1940s to 1960s, working with many tribal nations in the state. He was credited with developing some of the first college courses in Indian literature and helped found MSU's Museum of the Rockies. He wrote his anthropology doctoral thesis on "The Montana Cree: A Study in Religious Persistence." His biography notes that he was adopted into the Flathead tribe in 1937 and made part of the Northern Cheyenne Council of Forty in the 1950s. He spent years visiting Chippewa and Cree communities and wrote detailed descriptions of their sacred Sun Dance ritual. Today, on the Rocky Boy's Reservation, Dusenberry's name is a watchword for what not to put into the tribal histories. Stone Child College cultural programming chairwoman Louise Stump explains the problem with Dusenberry's Sun Dance writings. While the tribe's "The History of the Chippewa Cree of Rocky Boy's Indian Reservation" has several mentions of the Sun Dance, the book only brings up the time a Montana governor tried to ban it or newspaper accounts of upcoming dances. "We've been burned a lot of times," Stump said. "Other tribes and nations do ceremonies for big, huge prices. Especially in Europe. We don't want fake medicine people selling fake credibility by claiming they know the secrets of our rituals. We frown on that." But Dusenberry's depictions of the Cree Sun Dance have earned him special ire at Stone Child. "Some things should be for tribal members only," Stump said. "That man was told not to write about our Sun Dance ceremony. He went ahead and made a lot of money. Then he died of head cancer. The tumor attacked his head." |

Fort Belknap Agency map |

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008 of Paul C.

Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

FORT

BELKNAP - Minerva Allen tells a story about Inkdomi, the Assiniboine

trickster god, and the day he discovered red berries floating in

the water.

FORT

BELKNAP - Minerva Allen tells a story about Inkdomi, the Assiniboine

trickster god, and the day he discovered red berries floating in

the water.  Sharing

the stories

Sharing

the stories New

role, new challenge

New

role, new challenge