|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

January 1, 2009 - Volume

7 Number 1

|

||

|

|

||

|

Teaching Indian Languages

Preserves Heritage, Too

|

||

|

by Lynda V. Mapes -

Seattle Times staff reporter

|

||

|

credits: photos by Erika

Schultz - The Seattle Times

|

|

As the number of elders whose native tongue is their first language pass on, tribes are racing to preserve their languages. They are compiling the first dictionaries for languages that were entirely oral; recording elders; transcribing tapes; and especially, teaching the next generation of speakers.

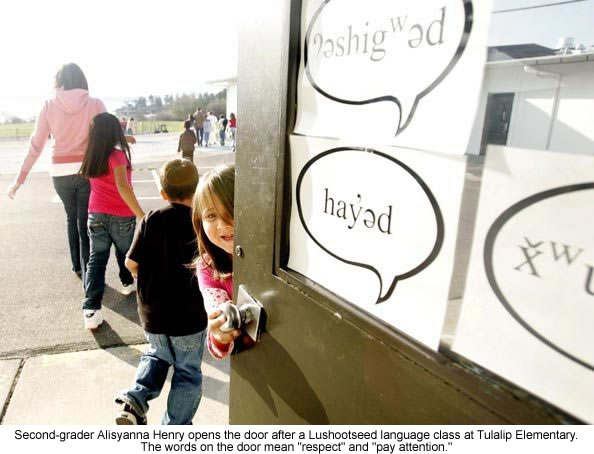

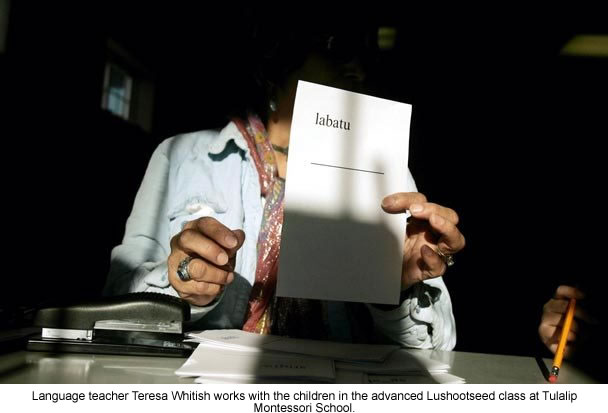

The kids want to show off what they have learned. Many have been getting 40 minutes of Lushootseed instruction a day at Tulalip Elementary, a public school in Snohomish County. Teacher Natosha Gobin gets instant decorum just by promising to call on whoever is sitting quietly, so eager are her students for a turn at the board. As the number of elders whose native tongue is their first language pass on, tribes throughout Washington and the rest of the country are racing to preserve their languages. They are compiling the first dictionaries for languages that were entirely oral; recording elders; transcribing tapes; and especially, teaching the next generation of speakers. The program, run and paid for by the Tulalip Tribes, has grown since 1993 to 12 employees, including seven full-time instructors teaching some 500 students, from low-income preschool kids to college- level classes. Some 80 percent of the students in the Tulalip Elementary classes are Indians, but their nonnative classmates are just as interested. By fourth grade, many are speaking sentences, writing and following Gobin's commands, all in Lushootseed. The students seem to take to the language — a tongue twister to the uninitiated — with ease, especially in the earliest grades, where kids shout out the names of animals they recognize in their homemade Lushootseed lesson books. Nothing in the curriculum is off the shelf; instructors create all the lesson and curriculum materials. "I love teaching them something positive, that they can't get anywhere else," Gobin said of her students. "That gives them pride, and it's something that helps bring the community together." Language is also an intimate connection with culture. "The language is who you are, it's that anchor, it's another way to believe in yourself, to know yourself," said Mel Sheldon, chairman of the board of the Tulalip Tribes.

"It's a very woeful situation," Krauss said. Languages are repositories of knowledge: local, historic and environmental, specific to their place. Every language contains unique cultural information, such as concepts of kinship and time. There are about 16 native languages still spoken in Washington. They are languages as musical as their names: Makah; Okanagan, Klallam, Quileute, Lushootseed. "People who haven't heard our language, the first thing they say is how beautiful it is," Gobin said of her native tongue. Even for the Tulalips, comparatively better off because of casino wealth than many others, language recovery is a tall order. There is no classroom instruction available in the middle- school grades, because of a lack of teachers. When the Tulalips sought to recruit teachers, there were only three applicants, said language-program director Michele Balagot. And she knows how hard it is to compete with the cacophony of mainstream American culture. "My daughter would rather be playing Nintendo," she said of her 8-year-old.

"It's a priority," said principal Teresa Iyall-Williams at Tulalip Elementary. Language instruction boosts native students' achievement, she said. "It increases engagement when they are able to see themselves in the curriculum." Non-Indian students benefit, too: At Port Angeles High School in Clallam County, where the student body is about 97 percent nonnative, Lower Elwha Klallam language instructor Jamie Valadez has since 1999 taught Klallam as one of the elective languages any student can take. Her classes are made up not only of students from Lower Elwha and other tribes but nonnative teens curious to learn. "It is just something they are interested in and enjoy, they are fascinated with learning about the native culture," Valadez said. Learning another language also hones her students' knowledge of English grammar and syntax, which they use to decode and build sentences in Klallam. The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe began its language program in 1991. The tribe is fortunate to have recordings of elders made by linguists and anthropologists dating back to the 1950s, a trove of tapes tracked down by the tribe in university collections and elsewhere. Hours of the tapes were painstakingly transcribed by Lower Elwha Klallam elders Bea Charles, 90, and Adeline Smith, 91. "That is really the biggest achievement," Valadez said. "Otherwise we wouldn't even know what those tapes say." Charles and Smith also are working to create the tribe's first dictionary, with the help of Tim Montler, a visiting linguist from the University of North Texas. Elders working to keep their tribes' languages in use were ceremonially wrapped in blankets at a dinner hosted by the Skokomish tribe last year to honor them for doing work no one else can — before it's too late. Charles seemed to speak for many as she told of the passion she holds for keeping her tribe's language alive. "I will teach," she said, "until my last breath." Lynda V. Mapes: 206-464-2736 or lmapes@seattletimes.com |

Tulalip, Washington map |

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009 of Vicki

Barry and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008 of Paul C.

Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

TULALIP

INDIAN RESERVATION - This classroom at first sounds like any other,

as fourth- and fifth- graders belt out the Pledge of Allegiance.

But then they slip seamlessly into Lushootseed, one of Washington

state's native languages.

TULALIP

INDIAN RESERVATION - This classroom at first sounds like any other,

as fourth- and fifth- graders belt out the Pledge of Allegiance.

But then they slip seamlessly into Lushootseed, one of Washington

state's native languages. Dwindling

languages

Dwindling

languages Resurrecting

a tongue

Resurrecting

a tongue