|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 1, 2008 - Volume

6 Number 3

|

||

|

|

||

|

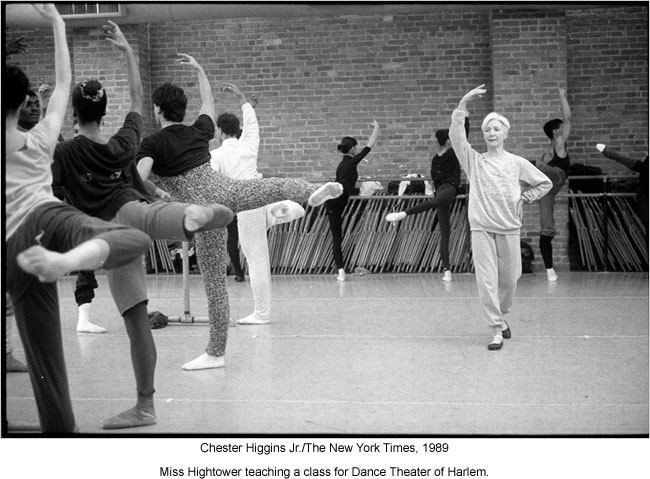

Rosella Hightower,

Prima Ballerina and School Founder, Is Dead at 88

|

||

|

by JACK ANDERSON - The

New York Times - Published: November 4, 2008

|

||

|

Her daughter, Dominique Monet Robier, told Agence France-Presse that her mother died overnight, late Monday or early Tuesday, after suffering several strokes. Miss Hightower was adored in Europe. After winning praise in the United States during the 1940s for her performances with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Ballet Theater (as American Ballet Theater was known then) and Col. W. de Basil’s Ballets Russes, she went to Europe with the Grand Ballet de Monte Carlo (later called the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas), and became the first 20th-century American ballerina to hold a leading place on the European stage. Yet she remained proud of being not only an American ballerina but also a Native American ballerina, of Choctaw descent. She was one of five Oklahoma-born American Indian ballerinas whose careers began in the 1940s, the others being Yvonne Chouteau, Moscelyne Larkin and the sisters Maria Tallchief and Marjorie Tallchief. In 1991 the State of Oklahoma honored the five dancers when it dedicated a mural depicting them, titled “Flight of Spirit,” in the Great Rotunda of the State Capitol in Oklahoma City. Miss Hightower won acclaim as early as 1943, when her dancing in the “Nutcracker” pas de deux with Ballet Theater caused John Martin, the dance critic of The New York Times, to declare, “Here, assuredly, is an American ballerina in the full sense of the term.” In 1947, as a member of the de Basil company, a theatrical emergency made Miss Hightower an overnight sensation. Alicia Markova had been scheduled to portray the title role in “Giselle” at the troupe’s opening performance on March 20 at the Metropolitan Opera House. But when Miss Markova fell ill, Miss Hightower, who had never danced the part before, learned it in only five hours. Her performance, Mr. Martin wrote, “exhibited not only the assurance of the fine trouper but also the quality of the genuine artist.” (Miss Markova died in 2004.)

Miss Hightower was born on Jan. 10, 1920 in Ardmore, Okla., the only child of Charles Edgar and Eula May Flanning Hightower. A few years later, when her father found a job with the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway, the family moved to Kansas City, Mo., where Miss Hightower received her early dance training with Dorothy Perkins. When the great choreographer and character dancer Léonide Massine appeared with the de Basil company in Kansas City in 1937, he invited Miss Hightower to Monte Carlo to join a new company he was organizing there. Arriving in Monte Carlo at her own expense, she found to her horror that she had no firm contract and that Massine was merely inviting people for further auditions. Miss Hightower was eventually accepted into the new Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. A hard worker and a quick learner, she soon received Massine’s encouragement. It was also with the Ballet Russe that she first met André Eglevsky, who was to be her partner with several companies. After World War II broke out, the Ballet Russe moved to New York. There, Miss Hightower became interested in the newly established Ballet Theater, joining it in 1941. In 1946 she joined the de Basil Ballet, which was then billing itself as Original Ballet Russe. Besides Massine, Miss Hightower worked with choreographers like Antony Tudor, Agnes de Mille and Bronislava Nijinska as she developed a remarkable versatility. But the greatest influence on her was Nijinska. Miss Hightower told the dance writer Lili Cockerille Livingston in “American Indian Ballerinas” (University of Oklahoma Press, 1997) that it was from Nijinska that she had truly learned the importance of rhythm in dancing. In 1947 Miss Hightower made what was perhaps the most significant decision in her career. She accepted an invitation to become ballerina of a company being formed in Europe by the Marquis George de Cuevas, a Chilean-born patron of the arts. The Marquis kept renaming his troupe, at various times calling it Grand Ballet de Monte Carlo and Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas. But most dancegoers referred to it simply as the de Cuevas Ballet. One reason for joining de Cuevas was the fact that Miss Hightower’s mentor, Nijinska, was working with the company. For Miss Hightower, Nijinska choreographed the glitteringly virtuosic “Rondo Capriccioso.” With de Cuevas, Miss Hightower triumphantly danced the classics as well as many new ballets. Her greatest success in the modern repertory was John Taras’s “Piège de Lumière,” in which she portrayed an exotic butterfly who bewitches escaped convicts in a tropical forest. Because Miss Hightower kept so busy in Europe, America saw little of her at the height of her powers. When the de Cuevas Ballet gave its only New York season in 1950, its leading dancers, Miss Hightower among them, were cheered. But the engagement as a whole was considered disorganized. Miss Hightower made a successful return to Ballet Theater as a guest artist during the 1955-56 season. After de Cuevas died in 1961 and his company disbanded, Miss Hightower gradually retired from the stage, although she gave a series of successful gala performances with Sonia Arova, Erik Bruhn and Rudolf Nureyev in 1962. She settled in Cannes, where in 1962 she opened the Centre de Danse Classique, soon recognized as one of Europe’s leading ballet schools. Miss Hightower also directed major companies, including the Marseilles Ballet (1969-72), the Ballet of the Grand Théâtre of Nancy (1973-74) in France and La Scala Ballet (1985-86) in Milan. Her greatest challenge came as director of the Paris Opéra Ballet (1980-83), a huge company celebrated for its glorious history, unique style and bureaucratic red tape. Yet she successfully reorganized it before turning it over to her successor, Nureyev. In 1991 the French experimental choreographer François Verret made a documentary film in homage to her, titled “Rosella Hightower.” Miss Hightower married the French designer and artist Jean Robier in Paris in 1952. Their only child, Dominique Robier, was born in 1955. Ms. Robier, also a dancer, has performed with Maurice Béjart’s ballet company and the modern-dance groups of Régine Chopinot and Dominique Bagouet. No other information about survivors was available. In 1975, the French government named Miss Hightower a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, the country’s premier honor. |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 of Vicki Barry

and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008 of Paul C.

Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

Rosella

Hightower, an Oklahoma-born ballerina of enormous flair and virtuosity

who followed up a celebrated international career by founding the

Centre de Danse Classique in Cannes, France, one of the world’s

leading ballet schools, has died at her home in Cannes, her daughter

said Tuesday. Miss Hightower was 88.

Rosella

Hightower, an Oklahoma-born ballerina of enormous flair and virtuosity

who followed up a celebrated international career by founding the

Centre de Danse Classique in Cannes, France, one of the world’s

leading ballet schools, has died at her home in Cannes, her daughter

said Tuesday. Miss Hightower was 88.