|

Canku Ota

|

|

|

(Many Paths)

|

||

|

An Online Newsletter

Celebrating Native America

|

||

|

December 1, 2008 - Volume

6 Number 3

|

||

|

|

||

|

Native exposure:

Lee Marmon's photography

|

||

|

by Eleanor LaBeau -

Sacramento (CA) News & Review

|

||

|

credits: {credits}

|

|

A

UC Davis exhibit of photographer Lee Marmon’s 60-year career,

from reservation life to Palm Springs’ golfing glitterati

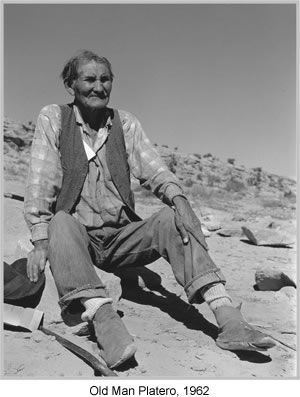

“It was just a magnificent day. The ocean was like glass. The high peaks had snow on them,” said Marmon, who recently spoke with SN&R. He spent the next few years working in a World War II military hospital on a remote Aleutian island. “I really wished I’d had a camera so I could send a picture home to my mom and dad.” He vowed to buy a “good camera” as soon as he left the Army. Three years later, Marmon was back home at Laguna Pueblo, a reservation 45 miles west of Albuquerque, N.M., where he was born and raised, learning how to use his first camera. It was a complicated Speed Graphic model, sans instruction manual, designed for professional shutterbugs. Then his father made an auspicious suggestion: “You ought to document some of the old ones so we won’t forget them.” Today, his images of tribal elders are the heart of a photographic oeuvre spanning six decades. The now 83-year-old Marmon, considered the “father of contemporary Native American photography,” has spent his life documenting Native American people and landscapes. And the exhibit Lee Marmon: Master Photographer, now at the C.N. Gorman Museum in Davis, is a short joy ride through a career that has taken Marmon from the Diné’s revered Canyon de Chelly to the White House, and from manicured SoCal golf courses to the cluttered workspace of Lucy Lewis, renowned Acoma Pueblo potter. This concise show of about 40 photos, arranged thematically by Gorman curator Veronica Passalacqua, brings into sharp focus the breadth and depth of Marmon’s lifework. Marmon

began his career by shooting elegant black-and-white portraits of

“the old ones.” A crisp 1949 image captures Jeff Riley

beating a drum for his grandkids, who, Marmon says, were dancing

outside the picture frame. Another, from 1963, advertises the power

of Walter Sarracino, then governor of Laguna Pueblo. He poses regally,

in suit and bowtie, holding the symbol of his office: a silver-tipped

Lincoln cane given to the tribal nation in 1863 by the 16th U.S.

president. (The cane symbolizes the sovereignty of Laguna government

and the United State’s trustee responsibilities to the tribe.)

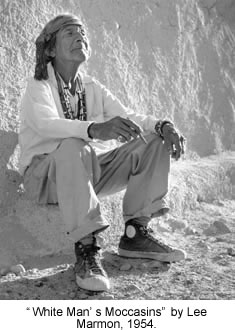

And there’s Marmon’s signature image, “White Man’s

Moccasins” (1954), which almost never happened.

The result of their collaboration is the now iconic photo of a contented, puckish “Old Jeff” basking in the sun, cigar in hand. He wears high-top Keds that clash with his traditional-looking head scarf and beaded necklaces. This internationally known image has come to symbolize the collision of cultures but also the resilience of Indian Country’s peoples. Marmon’s Native American subjects, unlike so many in the century or so following the invention of photography, chose when and how they represented themselves. As photographer, UCD professor and Gorman director Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie (Seminole/Muskogee/ Diné) puts it, “the history of Native American portraiture has always been the outside looking in at us, but Lee is from the community, looking at the community.

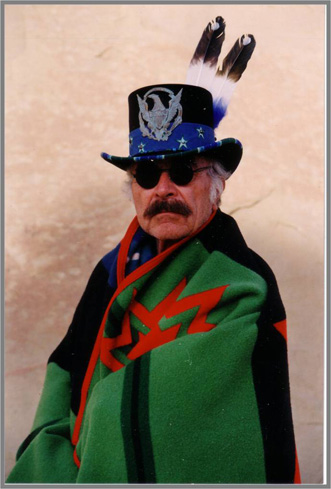

Professional Native American photogs were rare when Marmon began his pioneering career, and their work was not mass-circulated. But Edward Curtis’ turn-of-the-century sepia-toned photographs of indigenous peoples were everywhere. Marmon took a few tips on framing and composition from Curtis’ work, and then turned Native imagery upside down. While unsmiling, nervous faces haunt Curtis’ work, Marmon’s relaxed subjects let their personalities shine. His much-admired portraits of prominent Native artists are represented here by well-known color images from the ’70s and ’80s. Grace Medicine Flower (Santa Clara Pueblo), a potter noted for her delicate sgraffito technique, is stunning in a white pantsuit. If you look closely, you’ll notice a tiny, upside-down photographer in the gleaming surface of her hip-hugging silver-and-turquoise concho belt—it’s Marmon’s reflection. R.C. Gorman (Diné), who specialized in paintings of native women in traditional dress, leans on his easel, brush in hand, wearing a Sgt. Pepper’s-era psychedelic shirt. (His father was painter C.N. Gorman, after whom the UC Davis museum is named.) In the late 1960s, Marmon moved to Palm Springs and became the official photographer for the Bob Hope Chrysler Classic, a pro-golf tournament and glitterati photo op. Marmon’s job was to shoot photos for distribution on the news wires—and to stroke egos. “I took pictures of the golfers, of course, and lots of pictures of people coming to the annual Bob Hope Ball,” he says. “Half the time we never used that stuff; the wealthy people just wanted their picture taken to make them feel important.”

During these eight years, Marmon also met and photographed Wonder Woman, Dean Martin and Sammy Davis Jr. But the most exciting moment of his career? “You know Charo?” the veteran jokester asks, referring to the flamboyant entertainer. “She came down to talk to me about getting her pictures, and just as she got up, the crowd pushed her against me for about two minutes.” |

|

insert map here

|

www.expedia.com |

|

|

||

|

|

||

| Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments . We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. | ||

|

Canku Ota is a copyright ©

2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008 of Vicki Barry

and Paul Barry.

|

||

|

|

|

|

The "Canku

Ota - A Newsletter Celebrating Native America" web site and

its design is the

|

||

|

Copyright ©

1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005,

2006, 2007, 2008 of Paul C.

Barry.

|

||

|

All Rights Reserved.

|

||

One

spring afternoon in 1943, photographer Lee Marmon stood at the bow

of a passenger ship sailing into the harbor of Cordova, a tiny fishing

village along southern Alaska’s rocky coast. As he surveyed

the panorama, the straight-out-of boot-camp 19-year-old, traveling

with 200 fellow Army troops, had an epiphany of sorts.

One

spring afternoon in 1943, photographer Lee Marmon stood at the bow

of a passenger ship sailing into the harbor of Cordova, a tiny fishing

village along southern Alaska’s rocky coast. As he surveyed

the panorama, the straight-out-of boot-camp 19-year-old, traveling

with 200 fellow Army troops, had an epiphany of sorts. During

a packed talk in a UCD lecture hall a few weeks ago, a sprightly

Marmon recounted this near-miss to a rapt audience. The portrait’s

subject, Jeff Sousea, was camera-shy, though he routinely spun tall

tales for tourists who gathered at the Pueblo’s dusty plaza.

Marmon had pursued Sousea for a while, but was always rebuffed.

One day, while delivering groceries for his father’s trading

post, he tried again. “It just happened that I had my camera

in the pickup.” Marmon said. He also had a cigar.

During

a packed talk in a UCD lecture hall a few weeks ago, a sprightly

Marmon recounted this near-miss to a rapt audience. The portrait’s

subject, Jeff Sousea, was camera-shy, though he routinely spun tall

tales for tourists who gathered at the Pueblo’s dusty plaza.

Marmon had pursued Sousea for a while, but was always rebuffed.

One day, while delivering groceries for his father’s trading

post, he tried again. “It just happened that I had my camera

in the pickup.” Marmon said. He also had a cigar. “Lee

is not looking for the American Indian. He’s looking at friends

and family,” she adds.

“Lee

is not looking for the American Indian. He’s looking at friends

and family,” she adds. One

photo that never made the newswire is “Bob Hope With Presidents”

(1971); a group portrait of Hope; a widowed Mamie Eisenhower; Pat

and Richard Nixon; Spirow and Margaret Agnew; and Ronald and Nancy

Reagan, then California governor and first lady, all assembled at

the opening of the Eisenhower Medical Center in Palm Desert. Nixon

looks like a little boy standing up straight and tall for his picture.

Hope rolls his eyes at the ceiling. The only pair of eyes that engages

the viewer is President Dwight Eisenhower’s, staring down from

an oil portrait hanging on a wall. Everyone else gazes in different

directions.

One

photo that never made the newswire is “Bob Hope With Presidents”

(1971); a group portrait of Hope; a widowed Mamie Eisenhower; Pat

and Richard Nixon; Spirow and Margaret Agnew; and Ronald and Nancy

Reagan, then California governor and first lady, all assembled at

the opening of the Eisenhower Medical Center in Palm Desert. Nixon

looks like a little boy standing up straight and tall for his picture.

Hope rolls his eyes at the ceiling. The only pair of eyes that engages

the viewer is President Dwight Eisenhower’s, staring down from

an oil portrait hanging on a wall. Everyone else gazes in different

directions.